The Lost Art of Mapping City Fires

This map of the devastation wrought by the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 triggered an immediate memory. That malignant blob, devouring the heart of a city and then randomly stopping mid-street: I had seen its like before. On London Verbrandt, the title of a series of Dutch maps showing the smouldering remains of London’s Great Fire in 1666. England and the Netherlands were at war at the time, perhaps explaining the strategic importance of such maps to the Dutch — as well as providing a boost to morale (not quite Dutch courage, though).

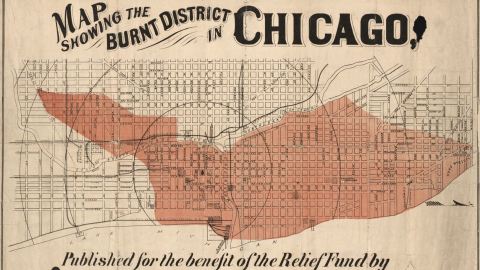

Chicago’s crispy bits (map by R.P. Studley Co., in the public domain, found here at the Library of Congress).

Urban fires were a recurring terror throughout most of human history. From time immemorial, when people first chose to live in compact, combustible surroundings, the generalized use of fire for cooking and heating was bound to cause the occasional inferno. London’s epic fire, for example, started for a very banal reason: Thomas Farrinor failing to turn off the oven of his bakery in Pudding Lane. The wooden frames of London’s houses and a fierce wind did the rest.

Many cities burned down — and were rebuilt — several times. And that’s just during peacetime. War only increased the risk of city fires, either due to civil disorder or as a deliberate military tactic. Both factors are said to have contributed to Moscow’s Great Fire of 1812, which levelled the city just as Napoleon entered it.

A crying London oarsman showing a tableau of his city burning (Map by Frederick De Wit, image in the public domain, found here on Barry Ruderman’s Rare Maps).

The last great city fires were the most apocalyptic ones, as Allied bombers created firestorms that laid waste to Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo. In the 21st century, cities don’t burn like they used to. We build in concrete and glass, not wood and thatch. And if a block does go up in smoke, we have professional firefighters to stop the blaze from taking out whole neighborhoods. Today’s out-of-control fires only occur in the wild, as so often happens in California’s parched interior.

The venerable cartographic niche of mapping city fires is now as extinct as the phenomenon itself. These fire maps came in two basic variants: either terrifying progress reports, with columns of smoke rising from city centres, or urban post-mortems, laying out the carbonised heart of the city. How far the art has declined can be seen from this example, a modern depiction of the oldest example listed below.

Great fire, not-so-great map. (Found here at Book of Days Tales)

The Great Fire of Rome started on the night of 18 to 19 July 64 and raged for six days before it was brought under control. It completely destroyed three of Rome’s 14 districts, leaving only four completely unscathed. The fire was blamed on Nero — the emperor who, as the proverb now says, “fiddled while Rome burned.” Wrong on two counts. One: Violins weren’t invented until the 16th century, so there were none to fiddle in first-century Rome (the contemporary accusations have him plucking a lyre). And two: Most scholars today agree Nero probably didn’t start the fire. Nevertheless, the emperor retaliated against the rumours by launching one of his own: that the Christians had started it — thus launching the first full-scale persecution against the new faith.

In 532, the Nika Riots in Constantinople resulted in nearly half the city being burned down. The worst riots the city has ever seen had their origins in the rivalry between the city’s “green” and “blue” factions — a cross of sports fans (notably of the chariot races), street gangs and political parties. At one race in the Hippodrome, the two factions united in shouting, “Nika!” (“Win!”) in opposition to emperor Justinian, besieging him for five days in his palace and electing a rival emperor before turning on each other. The resulting chaos saw half the city burned down, including the Hagia Sophia, which Justinian would later rebuild.

London’s Great Fire of 1666 was but one of many that ravaged the city. Other London fires raged in 1130, 1132, 1220, 1227, 1299, and 1633. But there were two other, bigger conflagrations that each, to their contemporaries, was also known as the Great Fire of London. The first, in 1135, started either on London Bridge or in the home of Gilbert Becket, Sheriff of London and father of Thomas Becket. The second started in 1212 in Southwark, working its way north to London Bridge. The stone bridge survived, but the houses built on in went up in flames. Those flames also trapped many who were rushing across the bridge to help fight the fire. Up to 3,000 Londoners are said to have died on the bridge alone — the biggest single loss of life in its history, a lugubrious extreme still listed by Guinness World Records.

London verbrandt: one of several Dutch maps revelling in England’s misfortune. (Engraving by Schut, image in the public domain, found here at the British Library)

For most of the two centuries between 1150 and 1350, Hangzhou was the world’s biggest city, numbering up to 2 million inhabitants. The Chinese metropolis also was one of the world’s most flammable cities: Large sections of the city, densely packed with wooden buildings, burned down in 1132, 1137, 1208, 1229, 1237, and 1275. The government established an elaborate fire-fighting system, with watchtowers exchanging lantern and flag signals to point to the origin and direction of fires, and over 3,000 soldiers tasked with putting them out.

Edo, the city now known as Tokyo, was also called the “City of Fires” — so frequent were the urban fires that swept through it. One of the worst ones, the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 destroyed up to 70 percent of the city and is said to have killed more than 100,000 people. Legend has it that the fire started when a priest tried to burn a cursed kimono, which had been owned by three girls who had all died before they could wear it. Hurricane-force winds helped the fire tear through the city, built mainly from wood and paper. Many victims of the fire were buried in pits over which Ekō-in was built, the Hall of Prayer for the Dead, dedicated as the resting place for souls who do not leave relatives behind, including victims of natural disasters.

A quarter of NYC up in flames (Map from the NY Public Library, in the public domain, found here on Wikimedia Commons)

The First Fire of New York swept through the West Side of Manhattan on the night of 21 September 1776, soon after the British occupied the city in the Revolutionary War. It destroyed up to 25 percent of the city, with other parts plundered in the resulting mayhem. The British occupiers and American patriots accused each other of starting the fire, contributing to the distrust between both sides. It began in the Fighting Cocks, a tavern near Whitehall Slip and spread rapidly due to the dry weather and strong winds. Nearby residents fled with what possessions they could carry to the Commons, now City Hall Park. The fire is estimated to have destroyed 10 to 25 percent of the city’s then 4,000 buildings. The British suspected George Washington of ordering the torching of New York, while some Americans thought the fire gave the British cover to plunder the city. The American commander in chief, however, did not disapprove of the fire’s results. Commenting on the fire, he wrote: “Providence — or some good honest Fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves.” British-occupied New York was a more overcrowded place because of the fire, and a more paranoid one. The fire convinced the British to keep the city under martial law rather than return it to civilian rule. Incidentally, there would be a Second Fire of New York in 1835 and a Great Fire in 1845.

New York’s carbonisation up close (Image by Franz Xaver Habermann, in the public domain, found here on Wikimedia Commons)

Few know that on 8 October 1871, the day of the Chicago Fire, a far deadlier fire ripped through northwestern Wisconsin. While technically a forest fire that turned into a firestorm, the Peshtigo Fire deserves to be unforgotten, for it killed between 1,500 and 2,500 people — the most deaths by fire in U.S. history. That same day also saw fires destroy the Michigan cities of Holland, Manistee, and Port Huron. One theory, since discredited, proposed that the fires in Peshtigo, Chicago, and elsewhere in the region were caused by fragments from Comet Biela impacting on that day.

The Great Fire of Turku is still the largest urban fire in the history of the Nordic countries. In a single day in 1827, it destroyed 75 percent of the Finnish city, leaving 11,000 people homeless — only 27 were killed. After the fire, Finland’s former capital also lost its position as biggest city to Helsinki. Turku was rebuilt along a grid plan that would influence how other Finnish towns were laid out.

In 1917, the Great Thessaloniki Fire flattened two-thirds of the second-largest city in Greece, destroying 9,500 houses and leaving 70,000 homeless. The disaster caused half of the city’s considerable Jewish population to emigrate. At the time, the city was a transit center for Allied troops, mainly French and British, during the First World War. Drought and political chaos contributed to the extent of the fire, but also the fact that Thessaloniki lacked an organized fire brigade. There were a few firefighting teams, but they were privately owned by insurance companies, and only protected the properties of their clients. The Great Thessaloniki Fire was ecumenical, destroying three orthodox churches, 12 mosques, and 16 synagogues.

An ecumenical disaster. (Map in the public domain, found here at Wikimedia Commons)

On 24 March 1946, retreating Indonesian republican forces deliberately set fire to the city of Bandung. The Bandung Lautan Api (“Bandung Sea of Fire”) was an act of defiance of the independence fighters against the British commander who had ordered them to vacate the city. In Bandung today, a large torch-shaped monument marks where the Sea of Fire was sparked. A map of the area destroyed by the fire is not readily available online, perhaps reflecting the decline in inferno cartography.

Strange Maps #729

Got a strange map? Let me know: strangemaps@gmail.com.