Drowning Holland: how the Netherlands will survive in floating cities

- The Dutch are champions at defeating the sea, but even they must soon admit defeat, one expert claims.

- Professor Jan Rotmans says the only sensible way to manage rising sea levels is to organize a smart retreat.

- Even in a flooded Holland, the future is still bright: dealing with sea-level rise will become a highly exportable skill.

It’s the year 2121. Due to rising seas and subsiding terrain, much of Holland has flooded. But it’s been a managed retreat. The country that became famous in the 20th century for taming the North Sea has used the 21st to become expert at graciously, profitably giving way to it.

Against the wiles of Neptune

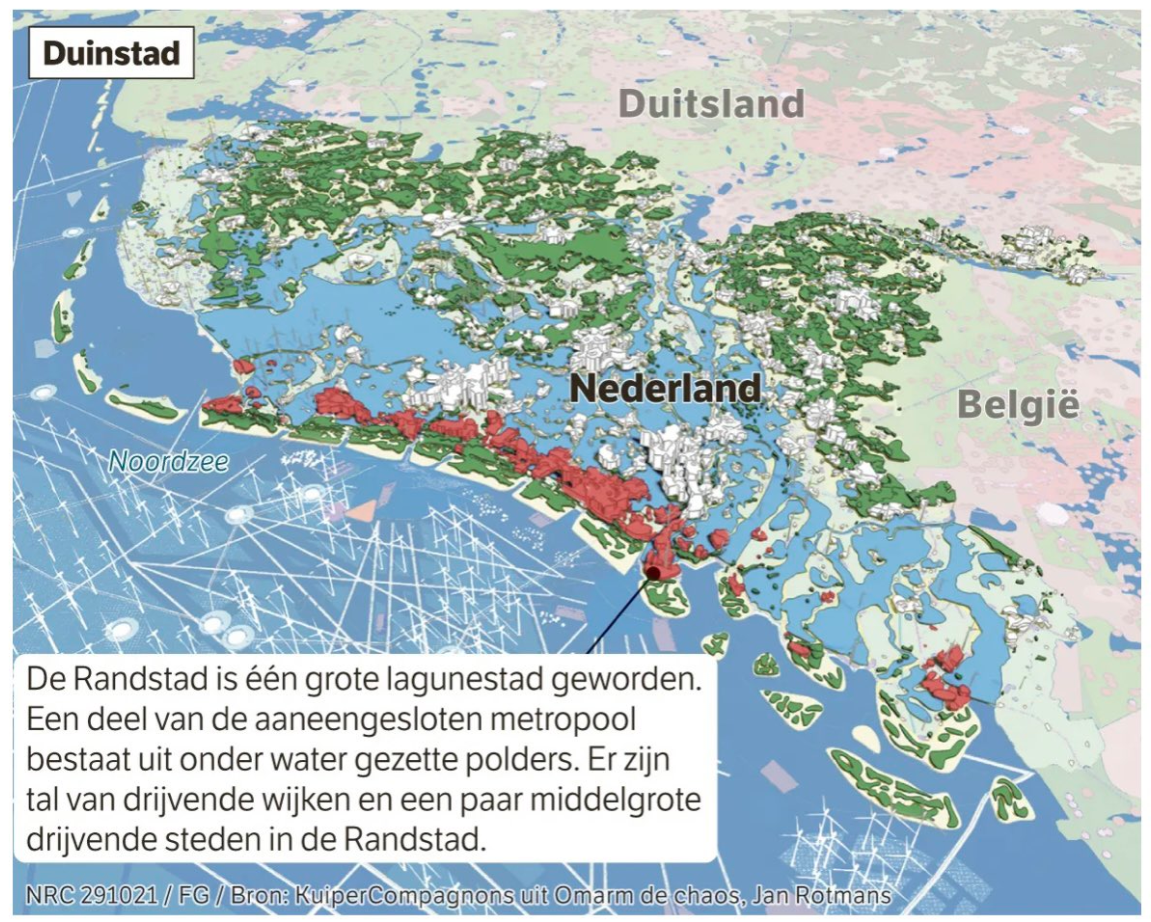

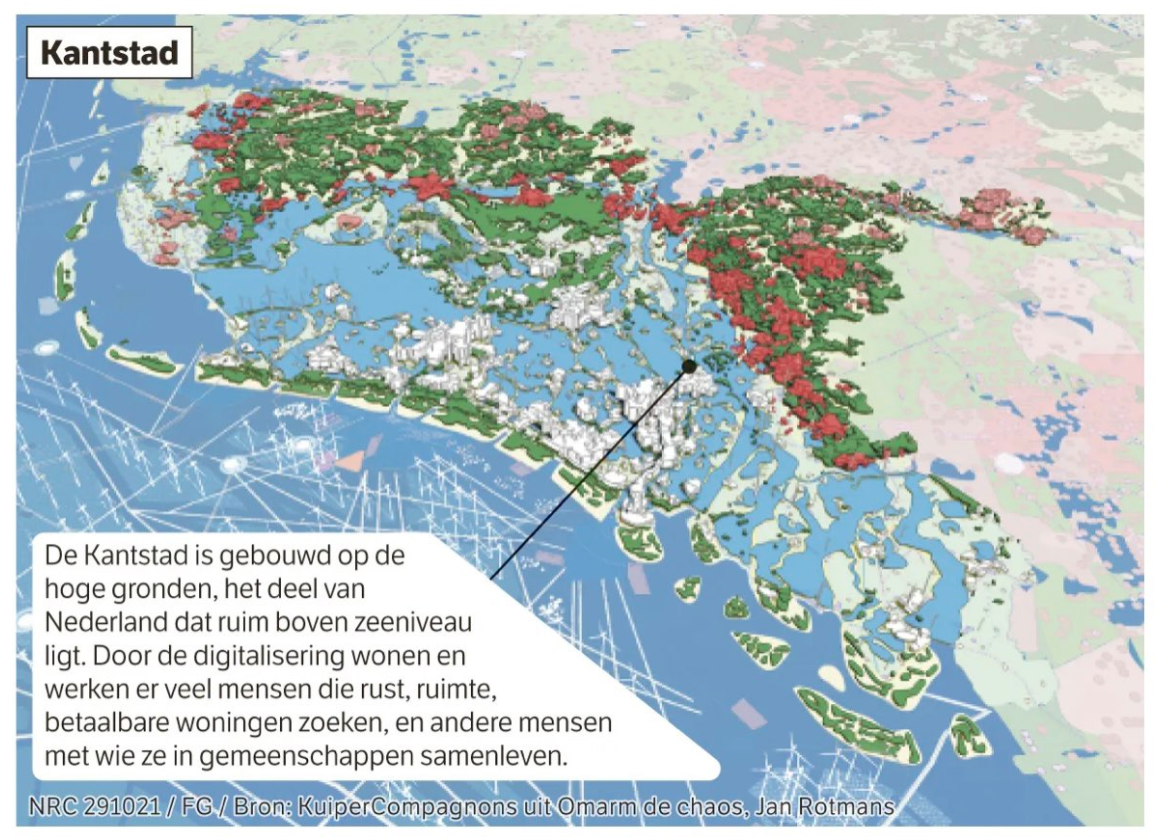

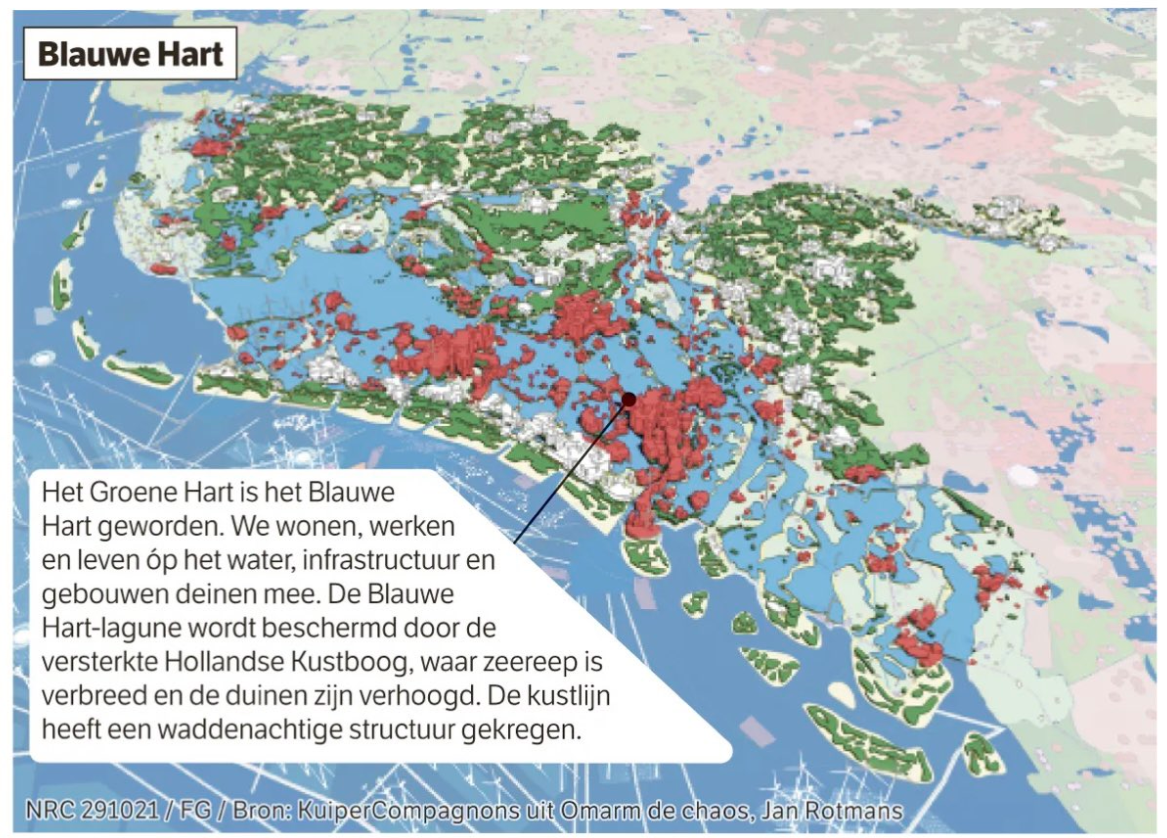

The Randstad, that massive conurbation of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht, is gone. Its Green Heart has been abandoned to the waves. But people still thrive in this new Blue Heart, and on either side of it: in Duinstad (“Dune City”), a strip of densely populated coastal islands, fortified against the wiles of Neptune; and in Kantstad (“Edge City”), a mix of urban and rural zones in the elevated interior of the Netherlands, now its new contact zone with the sea.

This is how Jan Rotmans, professor of Transition Management at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, sees the future. And it’s a best-case scenario, even though many of his compatriots might not agree.

They would argue that retreating from the sea is anathema to Dutch identity as well as the nation’s survival. Driving back the encroaching waves is what the Dutch have done for centuries. So-called waterschappen (“Water Boards”), elected bodies tasked with water management in specific regions, are often claimed to be the oldest democratic institutions in the country.

Retreat from the sea, a Dutch taboo

Following the catastrophic North Sea Flood of 1953, the Delta Works, completed in 1997, secured much of the lower-lying country behind a massive system of locks and barriers. At present, about 26% of the country is below sea level, and more than half of its 17.5 million citizens live in flood-prone areas.

Thanks to the Delta Works, and other massive engineering efforts, that risk is mainly theoretical. But not for ever, says Professor Rotmans in Omarm de Chaos (“Embrace the Chaos”), a book on the future of large-scale water management in the Netherlands. Its pugnacious title is meant to jumpstart a public debate on what is still largely a taboo subject in polite Dutch society: an organized retreat from the rising sea.

Based on credible scientific sources, Professor Rotmans predicts sea levels will rise 1 m (3.3 ft) over the next century. Due to subsidence, ground levels in large parts of the country will fall by equally as much, meaning the actual sea level will be 2 m (6.6 ft) higher by 2121.

As a result, some of the most densely populated parts of the Netherlands, already below sea level today, will be 8 to 10 m (26 to 33 ft) below. That will make getting and keeping the water out too expensive, Professor Rotmans argues. Not to mention too risky — the giant floods that hit Germany in August 2021 could just as easily have struck the Netherlands. And then there’s the fact that salinity inland is already increasing, due to the pressure of the seawater on the soil below the dykes and dams.

Floating cities will become commonplace

So, a smart, ordered retreat. Responsible flooding. Partially submerging Randstad. Haarlemmermeer, now a rural area at its center, a.k.a. the Green Heart, will return to its previous aquatic incarnation (meer is Dutch for “lake”). But people won’t entirely abandon the new Blue Heart. The Dutch are already experimenting with floating houses. From rarities, these will become commonplace. People will learn to live, work, and recreate in floating cities.

Meanwhile, the historic coastal cities will not be abandoned. They will be safeguarded as a Venice-like lagoon city on a strip of elevated and reinforced islands. These will be a continuation of the Wadden Islands that already dot the northern coast of the Netherlands. Like the original Wadden Islands, they will help protect areas further inland from assaults by the sea.

On those new shorelines inland we find Kantstad, a mix of urban and rural zones, focused on producing sustainable resources for a variety of industries, from clothing to construction.

Why so negative, Netherlands?

Together, these three cities are a new kind of place — no longer defined as a negative space. Not Neder-land (“the land below (the sea)”) but Boven-water (“above water”). These cities of the future will be powered by wind and solar energy, and its ports will do brisk trade in green hydrogen and the products of saline agriculture.

But perhaps the main export from Bovenwater will be knowledge — in water management, climate management, and sustainability. Expertise acquired in the 21st century, for success in the 22nd.

“Today, we face many challenges in one: climate, environment, agriculture, water, and energy. There is no other major river estuary in the world that faces so many problems all at once. If we start now, we still have time”, says Professor Rotmans. “The next ten years will determine whether we’ll make it or not. Strangely, I’m optimistic — we learn most in times of crisis.”

Maps found here on Jaap Modder’s Twitter, taken from the NRC newspaper. Original article here (behind paywall, in Dutch).

Follow Professor Jan Rotmans on Twitter and check out his website (in English). He wrote “Omarm de chaos” (in Dutch) together with architectural company KuiperCompagnons and with writer Mischa Verheijden.

Strange Maps #1120

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.