Fernanda, the Galápagos tortoise that came back from the dead

- A recent expedition found a Galápagos tortoise from a subspecies that had been thought extinct.

- “Fernanda,” as the individual has been named, is only the second of her kind ever found.

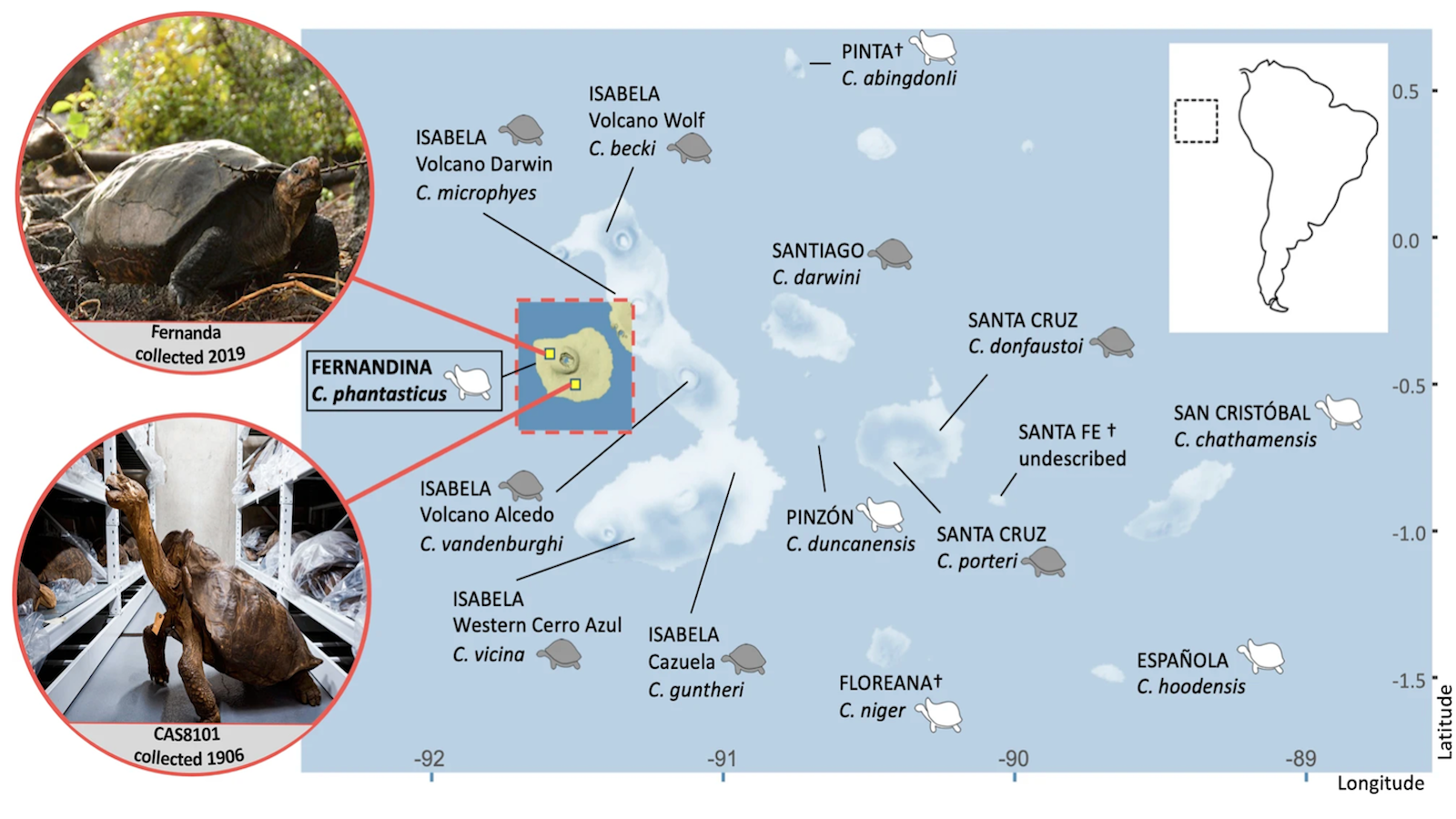

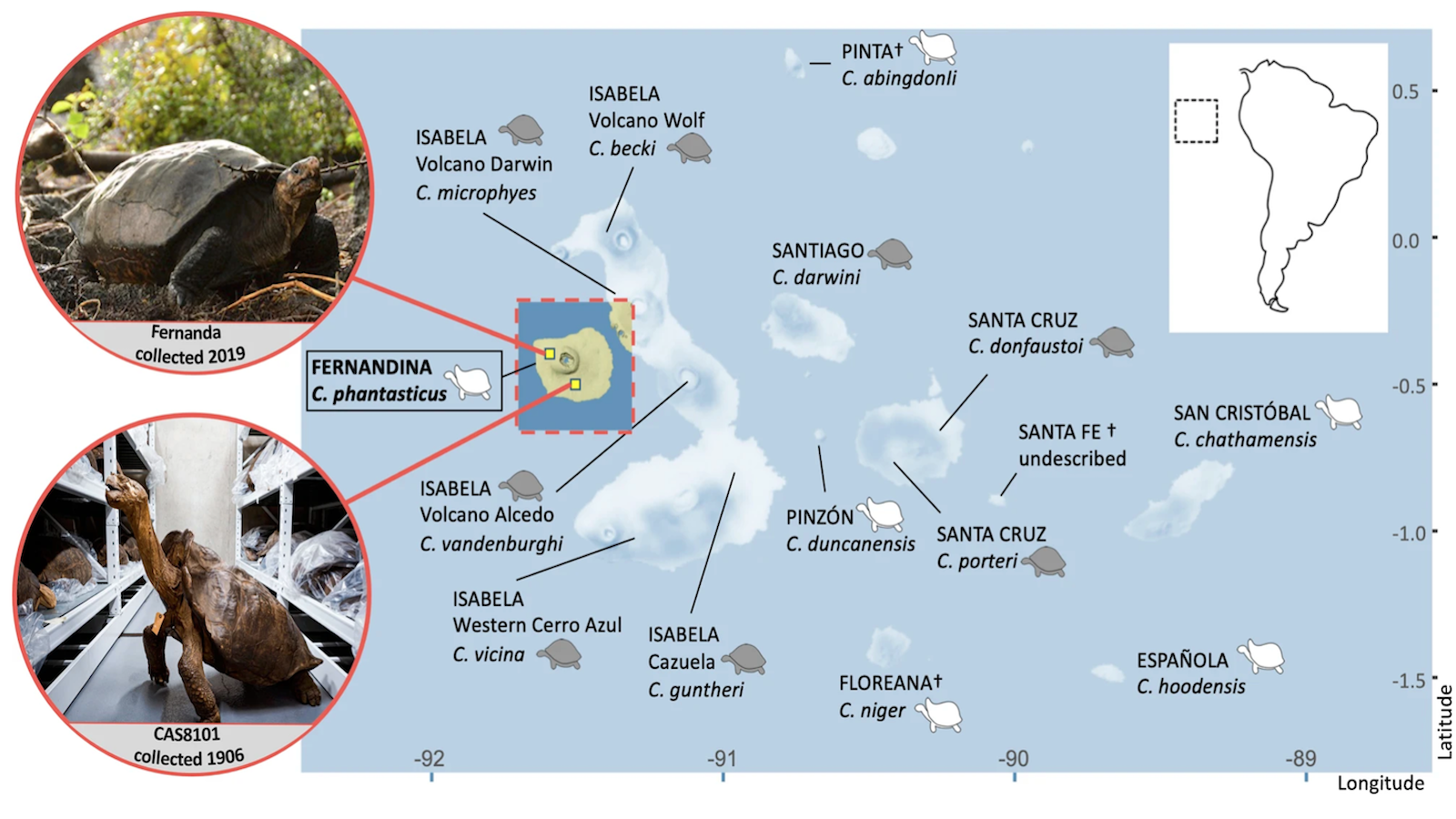

- This map shows her habitat and that of the other 11 surviving subspecies, made famous by Charles Darwin.

A rock star among animal species, the Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger) has produced a power trio of global celebrities: Lonesome George, the last of his kind; Diego the Playboy Tortoise, the first of many of his kind; and Harriet — formerly Harry — collected by Darwin himself, who died at 176, the oldest known specimen of its kind. We can now add Fernanda to that list. The fifty-something female is the first of her kind to be found in over a century, living proof that her subspecies is not extinct.

Fernanda, or “Fern” for short, was collected in February 2019 on Fernandina Island, the third largest of the 21 islands in the Galápagos archipelago, off the coast of Ecuador. Dominated by an active volcano, Fernandina is said to be the largest pristine island on Earth. Its lava flows don’t just impede human exploration and settlement; they had also cast doubt on the survival of a separate subspecies of the Galápagos tortoise on the island.

Tortoise scat and other circumstantial evidence

However, in May 2022, genome sequencing finally established that Fern is indeed a native of Fernandina. In other words, she belongs to Chelonoidis niger phantasticus, the same subspecies as a specimen collected on the island in 1906. Both are distinct from the other 11 surviving subspecies.

The 1906 specimen, the first and previously only of its kind ever found, was collected by famous Californian explorer Rollo H. Beck (after whom another subspecies is named). The Fernandina subspecies was named “phantasticus” for the extreme flaring of the male specimen’s saddleback shell, more prominent than in other subspecies elsewhere in the archipelago.

All subsequent evidence of giant tortoises on the Fernandina Island had been circumstantial: putative tortoise scat, an unconfirmed sighting in 2009, and cactus bite marks in 2013. Fern’s single-pawed resurrection of an entire subspecies is detailed in a paper published in the June 9, 2022 issue of Communications Biology. Finding a living individual of what was previously styled a “ghost tortoise” raises a number of questions. Most notably: Are there any other specimens of Phantasticus still alive on the island? And can they be captured and brought into a breeding program?

The giant tortoises of the Galápagos are not related to the giant tortoises still extant on the Seychelles. They diverged from their closest living relative, the much smaller Chaco tortoise from Paraguay and Argentina, between 6 and 12 million years ago. Some consider the dozen subspecies of the Galápagos tortoise distinct enough to label them separate species. Either way, they are all descended from a single ancestor.

Galápagos tortoises hate swimming

Two to three million years ago, a storm swept a tiny population of mainland giant tortoises (or possibly just one pregnant female) across from South America. The initial migration landed on one of the archipelago’s oldest islands, either Española or San Cristóbal. Since Galápagos tortoises don’t like swimming, they spread to other islands in the archipelago only by rare accident. In principle, they breed only with others on their own island, speeding up evolutionary divergence, a process also observed in Galápagos finches.

When the Spanish discovered the archipelago in 1535, they named the islands after their native giant tortoises (galápagos in Spanish). It’s estimated there were about a quarter of a million of them on the islands at that time. In the intervening centuries, the tortoises were hunted, and their habitat was destroyed by farmers and invasive species like pigs and rats. Because they could survive for more than a year without food or drink, they were often taken on board long-haul ships as an emergency supply of fresh meat.

A few subspecies didn’t survive human contact, and the rest didn’t fare too great either. A 1974 census showed there were slightly more than 3,000 giant tortoises left on the Galápagos. Thanks to various breeding programs, that number has now rebounded to about 20,000, although all surviving subspecies are still classified as various degrees of “threatened.”

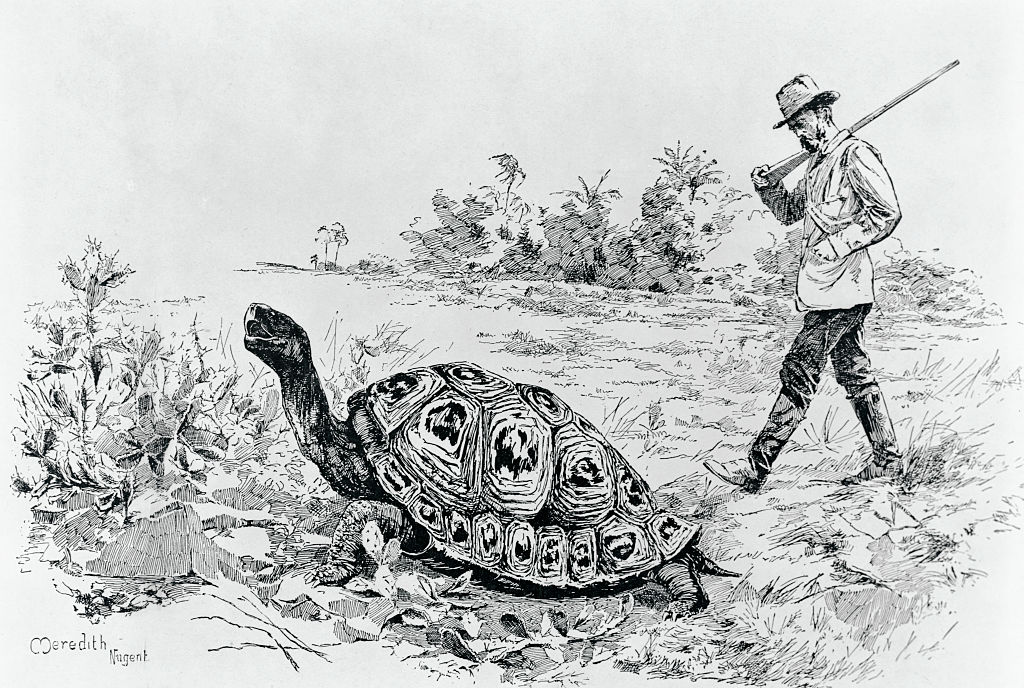

Charles Darwin, tortoise rider

In 1835, British biologist Charles Darwin visited the islands on the second voyage of the HMS Beagle. The tortoises were instrumental in helping him formulate the principle of natural selection, key to his theory of evolution.

In his journal, Darwin wrote:

“[T]he different islands to a considerable extent are inhabited by a different set of beings… the tortoises [differ] from the different islands… not only in size, but in other characters… I never dreamed that islands, about fifty or sixty miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted.”

He went on to write that “animals on separate islands ought to become different if kept long enough apart with slightly differing circumstances.” But the pioneer of evolutionary theory was not above some more basic interaction with the animals: “I frequently got on their backs, and then giving a few raps on the hinder part of their shells, they would rise up and walk away — but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.”

As Darwin noticed, the various subspecies have two main shell forms: saddleback (e.g., C. abingdonii) and domed (e.g., C. porteri). These shell forms exist in a continuum, from rounder in the east to the most saddleback-y on Fernandina. Saddleback subspecies tend to live on smaller, lower, drier islands with fewer food resources. Incidentally, one of the ways the animals get moisture is by licking dew off rocks, many of which have become indented from millennia of scraping by tortoise tongues.

12 subspecies remaining

This map shows the location of the newly resurrected subspecies and the others. In all, science distinguishes 15 subspecies, of which three are now extinct. The remaining 12 are spread across seven islands. An overview:

- Fernandina Island’s C. phantasticus was previously known only from a single specimen, collected in 1906. His taxidermied remains are known as CAS8101. The island, the westernmost in the archipelago, is uninhabited and has no predators, so it was speculated the species might have gone extinct from volcanic activity. In 2019, however, Fern was found, an elderly female of the subspecies. The expedition also found supporting evidence for more individuals at large on the island.

- Scientists debate whether the tortoises inhabiting neighboring Isabela Island, the largest in the archipelago, constitute a single subspecies or up to five distinct ones. This is partly because Isabela is the most recently formed island inhabited by the tortoises, giving them less time to diverge.

- C. becki, the one living in the Wolf Volcano on the island’s far northern side, is thought to have arrived separately from Santiago Island and is generally considered its own subspecies. It is named after the previously mentioned Mr. Beck, discoverer of the first specimen of the Fernandina Island subspecies.

- The other four subspecies are thought to be the result of another, later migration from Santa Cruz Island.

- C. guntheri is the descendant of the population that first colonized the Sierra Negra volcano.

- The tortoises then moved north toward other volcanoes: first to the Alcedo volcano, where C. vandenburghi lives.

- Then, on to the Darwin volcano, home to C. microphyes.

- C. vicina, living on Cerro Azul, the island’s southernmost volcano, is thought to be a more recent split from C. guntheri, and not as genetically different as C. vandenburghi or C. microphyes.

- Tiny Pinta Island used to have its own species, C. abingdonii. Their habitat was devastated by the introduction of feral goats. The last known individual of this subspecies was Lonesome George, who was discovered on the island in 1971. Born circa 1910, George died in captivity in 2012, after several unsuccessful mating attempts with hybrid females. It was previously assumed the Pinta Island subspecies was most closely related to the ones on nearby Isabela Island, but recent research shows it was actually genetically closer to C. chathamensis (which lives on San Cristóbal Island) and C. hoodensis (native to Española Island). These islands are much farther (about 190 miles, or 300 km), but there is a strong ocean current from both toward Pinta, which would explain the connection.

- Santiago Island consists of two overlapping volcanoes, last erupted in 1904-06. Its lush interior supports a wealth of wildlife, including C. darwini, a subspecies of giant tortoise named after the naturalist. Whaling ships and feral pigs and goats decimated the population in the 19th century. In recent years, assisted hatching and rearing programs have increased the population again to more than 1,000 individuals.

- The tortoises on Pinzón Island, C. duncanensis, are the smallest subspecies, reaching a maximum known weight of 168 pounds (76 kg) and a maximum shell length of 24 inches (61 cm). Black rats, introduced to Pinzón in the latter half of the 19th century, had eradicated generations of young tortoises. By the mid-20th century, only 100 to 200 adults survived. The island has been cleared of rats, and a breeding program has started to increase the population.

- On Santa Cruz Island, the tortoises occur in three distinct regions. Although they’re often grouped into a single subspecies named C. porteri, these three groups are more closely related to populations on other islands:

- the ones in Cerro Montura are closest to C. duncanensis on Pinzón Island,

- the group in Cerro Fatal is closest to C. chathamensis on San Cristóbal Island, and

- the tortoises in La Caseta to the four subspecies found in the southern part of Isabela Island, as well as the ones on Floreana Island.

- In 2015, after genetic analysis, the Cerro Fatal tortoises were reclassified as their own distinct subspecies, C. donfaustoi.

- Floreana Island used to have its own subspecies, C. niger, which is only known from fossils. However, hybrid descendants exist on Isabela Island. This raises the prospect of reconstructing the extinct subspecies through selective breeding. Although many hybrids between subspecies exist, they suffer from higher mortality and lower fertility than non-hybrid individuals.

- Santa Fe Island once also had its own subspecies, but evidence is so limited that it has not been fully described. The few bone fragments that survive indicate it was most closely related to C. hoodensis. That subspecies has been introduced onto Santa Fe to fill the ecological niche left by the Santa Fe tortoise.

- Prior to human contact, there were as many as 24,000 individuals of C. chathamensis on San Cristóbal Island. Human exploitation, as well as harm done by feral dogs and donkeys, reduced the to population to as few as 500 individuals in the 1970s. Dog eradication, nest fencing, and a breeding program have helped the population rebound quickly. In 2016, there were around 6,700 individuals, slightly more than half of which were juveniles.

- Just 14 individuals of C. hoodensis remained on Española Island in the 1960s and 1970s. The 12 females and 2 males lived separate from each other. To save the subspecies, the entire population was moved into a breeding program, which after more than 40 years has resulted in a healthy population of more than 1,000 individuals.

Returning to our original cast of characters, we are pleased to report that Fern is now at the Galápagos National Park Tortoise Center on Isabela Island, where she is receiving excellent care while researchers figure out how they can keep her (sub)species alive. Perhaps a future expedition will find a male companion for her.

Lonesome Fern or Playgirl Fern?

Failing that, she may suffer the fate of Lonesome George, who died the last of his subspecies in 2012. But where there’s life, there’s hope. George’s polar opposite is Diego, a now 100-year-old male who joined the breeding program for C. hoodensis from the San Diego Zoo. With a sexual appetite several magnitudes greater than that of Lonesome George, he fathered hundreds of individuals. About 40% of the current subspecies’ population is descended from Diego, who is also known as the “Playboy Tortoise.”

Fernanda still has time. She may be old in human years, but fifty-ish is fairly young for Galápagos tortoises, who are not just the world’s largest living species of tortoise; with lifespans easily exceeding 100 years, they’re also one of the longest-lived vertebrate species on the planet.

Perhaps the oldest known example is (or rather, was) Harriet, previously mistakenly identified as Harry. Harriet was a member of C. porteri, a subspecies from Santa Cruz Island. She died in 2006, a year after celebrating her 175th birthday. (It’s disputed whether she was actually that old.) She did survive Charles Darwin, who brought her to Europe in 1835, by more than 120 years.

Strange Maps #1158

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.