Kosovo land swap could end conflict – or restart war

Image: SRF

- The Yugoslav Wars started in 1991, but never really ended.

- Kosovo and Serbia are still enemies, and they’re getting worse.

- A proposed land swap could create peace – or reignite the conflict.

United Yugoslavia on a CIA map from 1990.

Image: public domain

The death of Old Yugoslavia

Wars are harder to finish than to start. Take for instance the Yugoslav Wars, which raged through most of the 1990s.

The first shot was fired at 2.30 pm on June 27th, 1991, when an officer in the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA) took aim at Slovenian separatists. When the YPA retreated on July 7th, Slovenia was the first of Yugoslavia’s republics to have won its independence.

Map of former Yugoslavia in 2008, when Kosovo declared its independence. The geopolitical situation remains the same today.

Image: Ijanderson977, CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikimedia Commons

After the wars

The Ten-Day War cost less than 100 casualties. The other wars – in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo (1) – lasted much longer and were a lot bloodier. By early 1999, when NATO had forced Serbia to concede defeat in Kosovo, close to 140,000 people had been killed and four million civilians displaced.

So when was the last shot fired? Perhaps it never was; it’s debatable whether the Yugoslav Wars are actually over. That’s because Kosovo is a special case. Although inhabited by an overwhelming ethnic-Albanian majority, Kosovo is of extreme historical and symbolic significance for Serbians. More importantly, from a legalistic point of view, Kosovo was never a separate republic within Yugoslavia but rather a (nominally) autonomous province within Serbia.

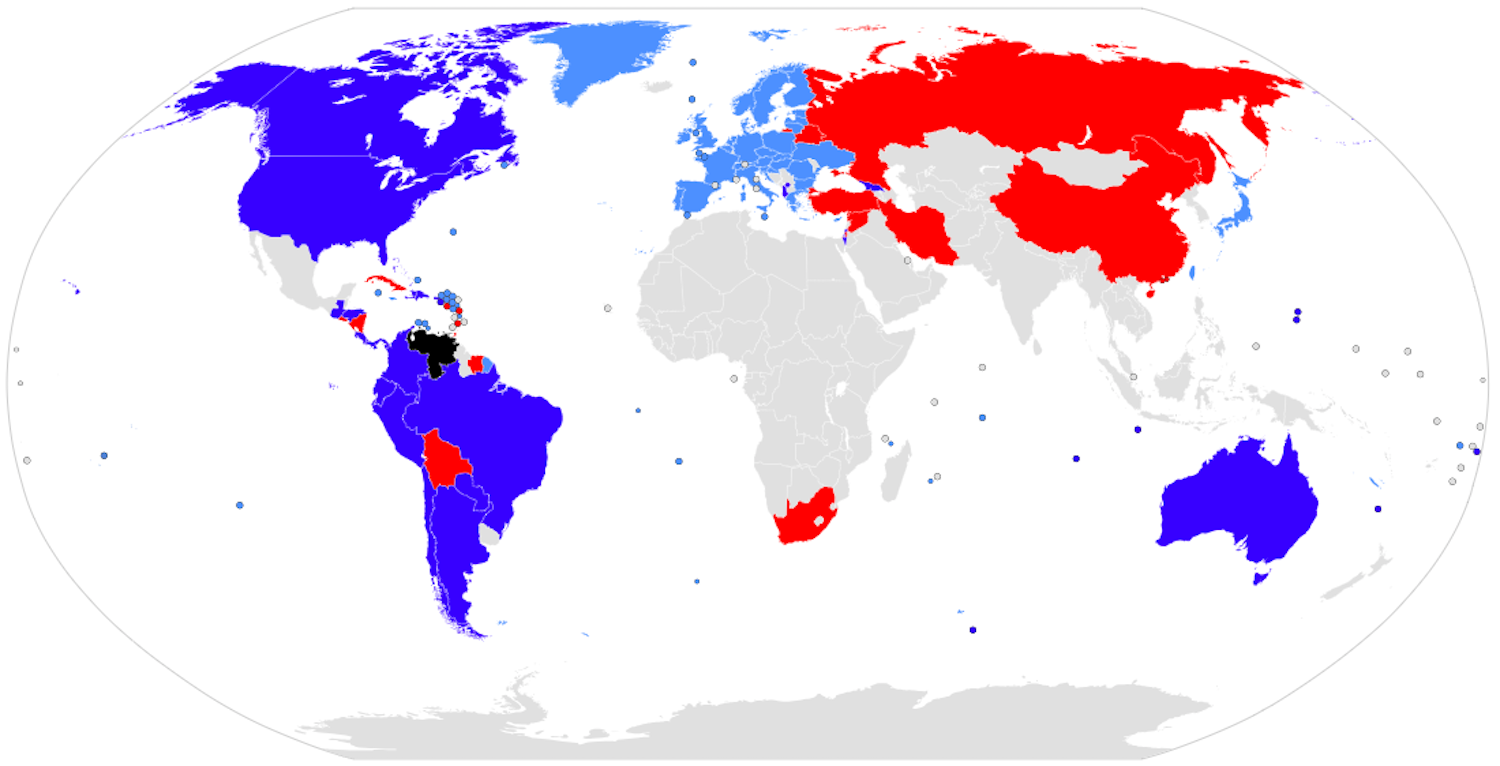

In red: States that have recognized the independence of Kosovo (most EU member states – with the notable exceptions of Spain, Greece, Romania and Slovakia; and the U.S., Japan, Turkey and Egypt, among many others).

In blue: States that continue to recognize Serbia’s sovereignty over Kosovo (most notably Russia and China, but also other major countries such as India, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and Iran). Image: Public domain

Kosovo divides the world

The government of Serbia has made its peace and established diplomatic relations with all other former Yugoslav countries, but not with Kosovo. In Serbian eyes, Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008 was a unilateral and therefore legally invalid change of state borders. Belgrade officially still considers Kosovo a ‘renegade province’, and it has a lot of international support for that position (2). Not just from its historical protector Russia, but also from other states that face separatist movements (e.g. Spain and India).

Despite their current conflict, Kosovo and Serbia have the same long-term objective: Membership of the European Union. Ironically, that wish could lead to Yugoslav reunification some years down the road – within the EU. Slovenia and Croatia have already joined, and all other ex-Yugoslav states would like to follow their example. Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia have already submitted an official application. The EU considers Bosnia and Kosovo ‘potential candidates’.

Kosovo is the main stumbling block on Serbia’s road to EU membership. Even after the end of hostilities, skirmishes continued between the ethnically Albanian majority and the ethnically Serbian minority within Kosovo, and vice versa in Serbian territories directly adjacent. Tensions are dormant at best. A renewed outbreak of armed conflict is not unthinkable.

Mitrovica isn’t the only area majority-Serb area in Kosovo, but the others are enclaved and fear being abandoned in a land swap.

Image: BBC

Land for peace?

In fact, relations between Kosovo and Serbia have deteriorated spectacularly in the past few months. At the end of November, Kosovo was refused membership of Interpol, mainly on the insistence of Serbia. In retaliation, Kosovo imposed a 100% tariff on all imports from Serbia. After which Serbia’s prime minister Ana Brnabic refused to exclude her country’s “option” to intervene militarily in Kosovo. Upon which Kosovo’s government decided to start setting up its own army – despite its prohibition to do so as one of the conditions of its continued NATO-protected independence.

The protracted death of Yugoslavia will be over only when this simmering conflict is finally resolved. The best way to do that, politicians on both sides have suggested, is for the borders reflect the ethnic makeup of the frontier between Kosovo and Serbia.

The biggest and most obvious pieces of the puzzle are the Serbian-majority district of Mitrovica in northern Kosovo, and the Albanian-majority Presevo Valley, in southwestern Serbia. That land swap was suggested the previous summer by no less than Hashim Thaci and Aleksandar Vucic, presidents of Kosovo and Serbia respectively. Best-case scenario: That would eliminate the main obstacle to mutual recognition, joint EU membership and future prosperity.

Belgium and the Netherlands recently adjusted out their common border to conform to the straightened Meuse River.

Image: Ruland Kolen

If others can do it…

Skeptics – and more than a few locals – warn that there also is a worst-case scenario: The swap could rekindle animosities and restart the war. A deal along those lines would almost certainly exclude six Serbian-majority municipalities enclaved deep within Kosovo. While Serbian Mitrovica, which borders Serbia proper, is home to some 40,000 inhabitants, those enclaves represent a further 80,000 ethnic Serbs – who fear being totally abandoned in a land swap, and eventually forced out of their homes.

Western powers, which sponsored Kosovo’s independence, are divided over the plan. U.S. officials back the idea, as do some within the EU. But the Germans are against; they are concerned about the plan’s potential to fire up regional tensions rather than eliminate them.

Borders are the Holy Grail of modern nationhood. Countries consider their borders inviolate and unchanging. Nevertheless, land swaps are not unheard of. Quite recently, Belgium and the Netherlands exchanged territories so their joint border would again match up with the straightened course of the River Meuse (3). But those bits of land were tiny and uninhabited. And as the past has amply shown, borders pack a lot more baggage in the Balkans.

Strange Maps #957

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) In contrast, the secession from Yugoslavia of both Macedonia (in 1991) and Montenegro (in 2006) was entirely peaceful.

(2) Including from Russia, which pointedly invoked Kosovar independence as a precedent for its own unilateral annexation of the Crimea in 2014. (See #662)

(3) See #635 for a pre-treaty discussion of the Belgo-Dutch land swap.