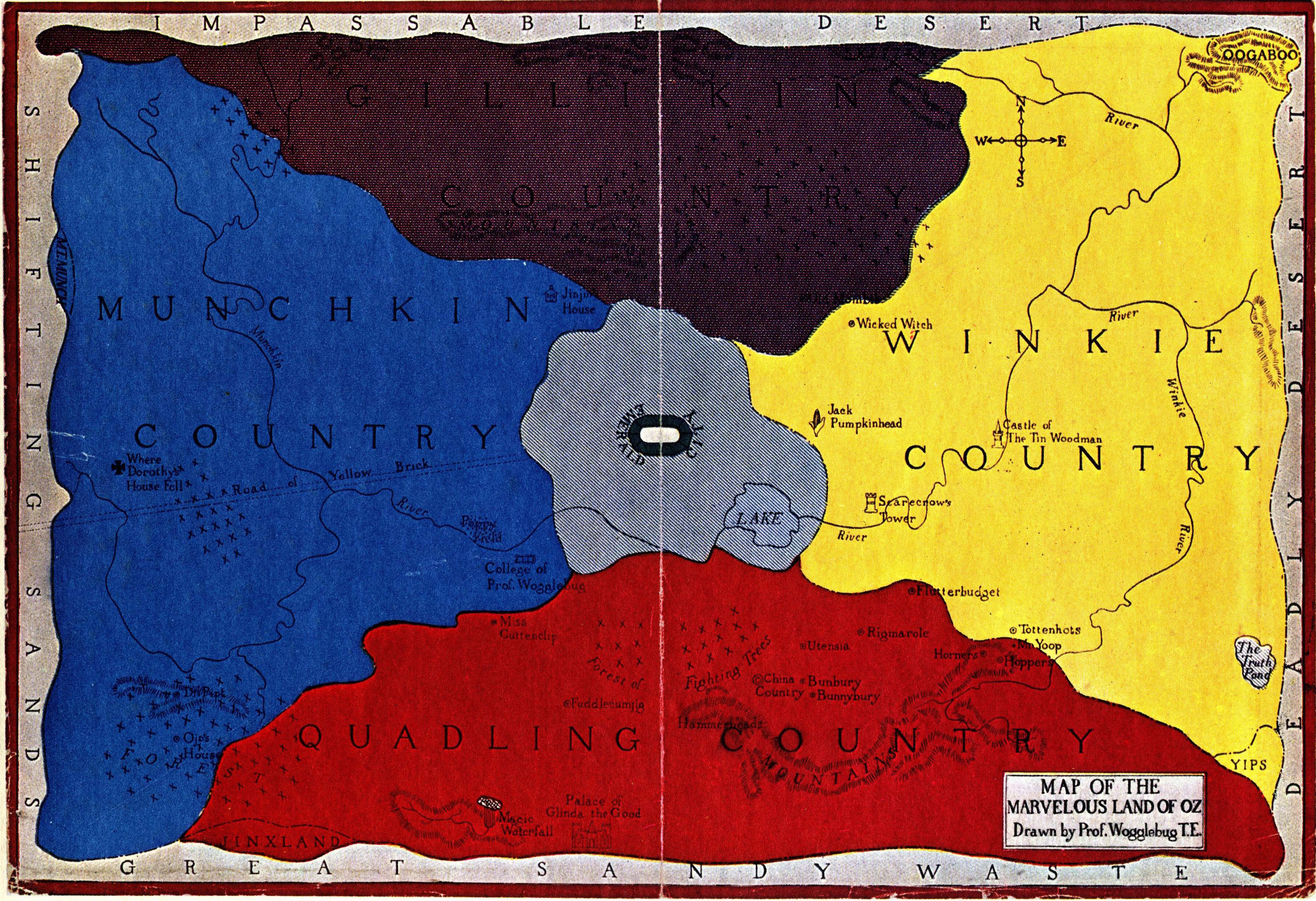

Why is Le Guin’s hand-drawn map not as famous as her book?

- Stevenson, Tolkien and Le Guin have all made maps to ‘illustrate’ their stories.

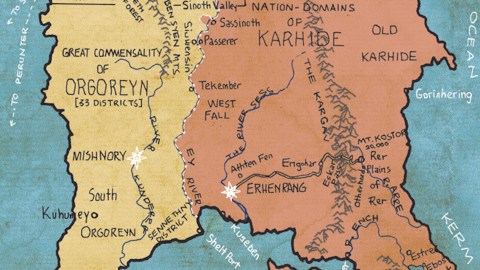

- Despite the iconic status of Le Guin’s 1969 novel The Left Hand of Darkness, her hand-drawn map of planet Gethen is quite unknown.

- The map focuses on Karhide and Orgoryen, the two main nations on the frozen planet and the locus of the action in Left Hand.

The map is half the story. Especially if the world in that story is entirely fictional. That’s why some authors are also cartographers. Stevenson drew the outline of Treasure Island before he spun the tale itself. You can follow the Fellowship’s quest to destroy the Ring on Tolkien’s spellbinding plan of Middle-Earth – the mother of all fantasy maps. Less well known is that Ursula K. Le Guin also mapped out the topography of her most famous book.

Le Guin’s 1969 novel The Left Hand of Darkness ranks high on lists of sci-fi classics. According to the critic Harold Bloom, “Le Guin, more than Tolkien, has raised fantasy into high literature, for our time”. Left Hand was popular as well as acclaimed. To date, more than a million copies have been sold.

If Le Guin’s hand-drawn map of the icebound planet Gethen is somewhat obscure, it’s perhaps because it seems to pop up for the first time only in the endpapers of The Hainish Novels & Stories. Published in 2017, the year before the author’s death, the two-volume collection is the first to unite all her work set in the universe of The Left Hand of Darkness.

The backdrop to that universe is the Ekumen, a galaxy-wide confederation of some 80 planets inhabited by humanoids. All are descended from the planet Hain, about 140 lightyears from Earth. The Ekumen works to reunite the far-flung Hainish colonies, despite the fact that genetic engineering and a million years of separate evolution have led to great cultural and biological divergences.

Volume one brings together the first five Hainish novels, including Left Hand, and two short stories. The second volume presents the final two novels (including The Word for World is Forest, the inspiration for the movie Avatar), seven short stories and a story suite in five episodes.

In her introduction to the boxed set, Le Guin writes that “The Universe in the 1960s was a man’s world – a remarkably chaste one (…) We followed the boys out among the stars”. Le Guin changed all that. The evolutionary divergence in the Hainish cycle allows her to explore gender relations and sexual politics in new and unexplored ways – boldly going where no man had gone before.

The Left Hand of Darkness reads as a report by Genly Ai, a man from Earth sent to Gethen to persuade its inhabitants to join the Ekumen. As the book starts, that mission is failing. Ai has trouble understanding Gethenian culture, which is rooted in the unique ambisexuality of the Gethenians. Most of the time, the locals are sexual neuters – they only turn male or female when they enter a state called kemmer. Depending on the interaction with a particular partner, Gethenians can then turn into either sex, and thus, depending on each interaction, either father or bear children.

After a year in Ehrenrang, the capital of the kingdom of Karhide, Ai finally obtains an audience with the king – only for him to reject the Ekumen. Ai then crosses over into Orgoryen, a communist-style republic and the only other major nation on Gethen. In the capital Mishnory, Ai seems to get more understanding and support than in Karhide. But he is eventually arrested and sent to die in a work camp in the far north. Ai is saved by Estraven, the deposed prime minister of Karhide. Both flee across the northern Gobrin ice sheet back to Karhide, where the story concludes.

Left Hand contains a lot of detail about Gethen, a planet so cold that the Ekumen also know it, simply, as Winter. Both Gethen’s atmosphere and gravity are similar to Earth’s, as are the lengths of its years and days. However, its orbit is quite different, producing long, extreme and planet-wide seasons. In the book, Gethen is gripped by an ice age, and there are extensive polar caps, all the way to at least 45° north and south. Snow and cold are omnipresent elsewhere too. Gethenians are physically adapted to the harsh climate: they are short and robust, similar to Inuit on Earth.

Le Guin’s map focuses on the Great Continent shared by Orgoryen in the west and Karhide in the east. A small inset at bottom left also shows the Sea Hemisphere, with a northern continent called Sith and a southern one called Perunter.

Karhide occupies the greater part of the continent it shares with its rival, Orgoryen. The Karhidian capital Ehrenrang is in the south, on the river Sess, close to the Gulf of Charisune. The centre of the country is separated by the Kargav Mountains from Old Karhide, on the east coast. To the north, towards the Pering ice sheet, is the Pering Storm Border.

The Ey river, rising just south of Guthen Bay and flowing all the way down to the Gulf of Charisune, forms most of the border between both countries. Like its opposite, the capital of Orgoreyn is located in the south, on a river, the Kunderer. While Karhide is a kingdom composed of ‘nation-domains’, Orgoreyn is a Great Commensality, divided into 33 districts.

The inset top left focuses on the northwest of the Great Continent. The border dispute in the Sinoth Valley could boil over into war. The farm where Ai is confined is in this area. And the escape route he and Estraven follow leads across the Gobrin Ice, immediately to the north.

One notable discrepancy between the main map and the inset top left: on the former, Orgoreyn touches the western shore of Guthen Bay, while on the latter a straight-line border clearly to the west puts Karhide in control of that area. On the main map, Kurkurast is in Orgoreyn, while that city is in Karhide on the smaller inset map. Is this a visualisation of the Sinoth Valley dispute? Having read the book quite some time ago, I can’t recollect any supporting evidence for or against this theory. But it’s not entirely plausible: the valley is located quite a bit further south.

Despite this (potential) flaw, Le Guin’s map of Gethen is an attractive companion to the story itself and deserves to be better known. And who knows? Last year, the tv rights for Left Hand were acquired by production house Critical Content, so chances are the map will soon flash across our screens.

Map found here at ursulakleguin.com.

Strange Maps #940

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.