Life, Liberty, and Free Beer: the Short-lived Free State of Schwenten

Comedy is tragedy plus time. Take, for example, the Freistaat Schwenten: founded under the shadow of war and disbanded amid great national trauma, this short-lived ministate’s memory was hijacked by the Nazis. Yet almost a century after its dissolution, the Free State’s main legacy are two hilarious anecdotes: the one about its navy and the frozen lake, and the one about its parliament and the free beer.

But first: the tragedy.

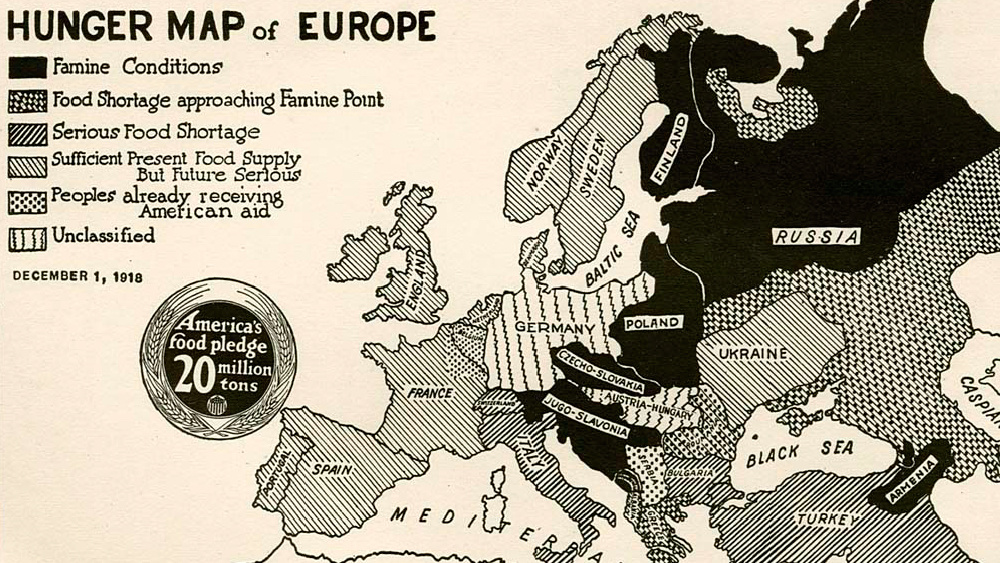

As if four bloody years of world war weren’t enough, the volatile eastern frontier of the crumbling Kaiserreich erupted in violence at the end of 1918, after Germany’s defeat in World War I. The fighting centered on what to the Germans was the Prussian province of Posen, named after its capital.

Prussia was the core state of the German Empire, but Posen was its only non-German province: fully two-thirds of its 2 million inhabitants were Polish (and Catholic), the German (and 90 percent Protestant) population was concentrated in the province’s west.

To the Poles, the city of Posen was Poznań, and the surrounding area was Wielkopolska, (“Greater Poland”), the historical core of the independent Polish state, wiped off the map after the Congress of Vienna (1815) divided what was left of Poland among Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

A German defeat would be the best opportunity in a century to get Poland back on the map, and sort out a large number of other injustices in Europe and the world. That at least was the idea behind U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points, formulated in early 1918. The 13th point stated that:

An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

Wilson’s explicit reference to Poland is largely due to Ignacy Paderewski, the famous piano virtuoso, who had been campaigning vigorously for Polish independence, in the U.S. and elsewhere. On 27 December 1918, Paderewski [1] gave a speech at Poznań, then still excluded from the fledgling new Poland coagulating west of imperial Germany’s borders. It was the start of a full-scale Polish rebellion against German rule.

The Free State of Schwenten

To the townsfolk of Schwenten, the escalating instability must have felt like a terrifying avalanche. The railway town of less than a thousand souls was predominantly German [2], and surrounded by villages that were mainly Polish. Schwenten sent out emissaries to German troops camped out in Glogau (now Głogów), across the provincial border in Silesia. They proved unwilling or unable to help defend the town against the Polish militias that were taking control of much of the area.

In desperation, the people of Schwenten took their fate into their own hands. At a town meeting on 5 January 1919 in the Gasthaus Wolff, the inhabitants of Schwenten declared their independence — and their neutrality. The Freistaat Schwenten was born. The most urgent point on the new state’s agenda was keeping the peace: Negotiations with the Polish commanders in the neighboring towns of Kiebel and Obra resulted in a non-aggression pact.

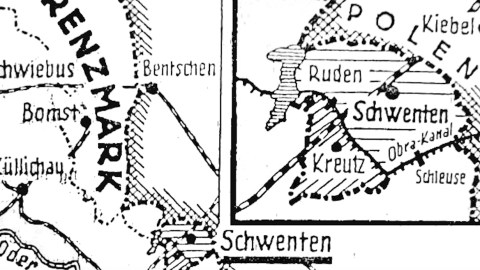

The worst fighting between Germans and Poles was over by 16 February 1919, when the Allies imposed an armistice and a demarcation line (largely along the divide that separated majority-German from majority-Polish areas, although the eventual border would be different still).

The government of the Free State.

But the Free State rambled on. Emil Gustav Hegemann, the local reverend, was elected president and foreign minister. Town mayor Heinrich Drescher was appointed minister of the interior, while Karl Teske, the forest warden, was appointed minister of war. Plans to appoint the village barber as minister of the navy came to naught, as the local lake was completely frozen.

Schwenten instituted a constitution, proclaimed laws and filed a budget. An aggravating circumstance for the latter was the fact that Schwenten was unable to tax its main export, beer. Herr Schulz, who ran the Gasthaus where the Schwenten Parliament held its meetings, had made it clear that he would no longer ply his guests with free beer if they levied a tax on the stuff.

The Freistaat managed to live in peace with its neighbors, both German and Polish. Both sides recognized the Free State’s neutrality. Foreigners who wanted to pass through town needed a visum, stamped by the local church office.

When it became clear that Schwenten would remain part of Germany, the state disbanded itself on 10 August 1919, declaring itself part of Germany. This only took effect on 9 June 1920, when the Treaty of Versailles came into force. To celebrate their curious, brief independence, the people of Schwenten held an annual Fest at the Historic Inn on 9 June, where the Entente Commission had come to approve its accession to Germany.

The Armistice line. Schwenten is to the northwest of Lissa (now Leszno).

The Nazis seized upon this annual celebration as an example of German heroism, with honchos like Reichsleiter Robert Ley and Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick participating in the annual celebrations.

After 1945, the area returned to Poland, and the remaining German population was expelled.

Schwenten today is called Świętno, a Polish village an hour and a half’s drive southwest of Poznań, lodged firmly and deeply inside Poland.

Schwenten wasn’t the only Freistaat to emerge from Germany’s post-war chaos. See #179 for the curious history of the Freistaat Flaschenhals (Bottleneck).

Many thanks to Ruland Kolen for sending in the map of the Freistaat Schwenten. Map of the Free State taken here at Wikipedia. Picture of the presidency taken here at Wikigag. Map of the armistice taken here at Wikipedia.

Strange Maps #718

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] Paderewski would go on to become the Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Poland, for most of 1919. He signed the Versailles Treaty for Poland, and would later become his country’s representative at the League of Nations.

[2] Wholly German according to German Wikipedia, mainly German on Polish Wikipedia. I guess this proves that objectivity is that arrangement of the facts which best suits your particular story.