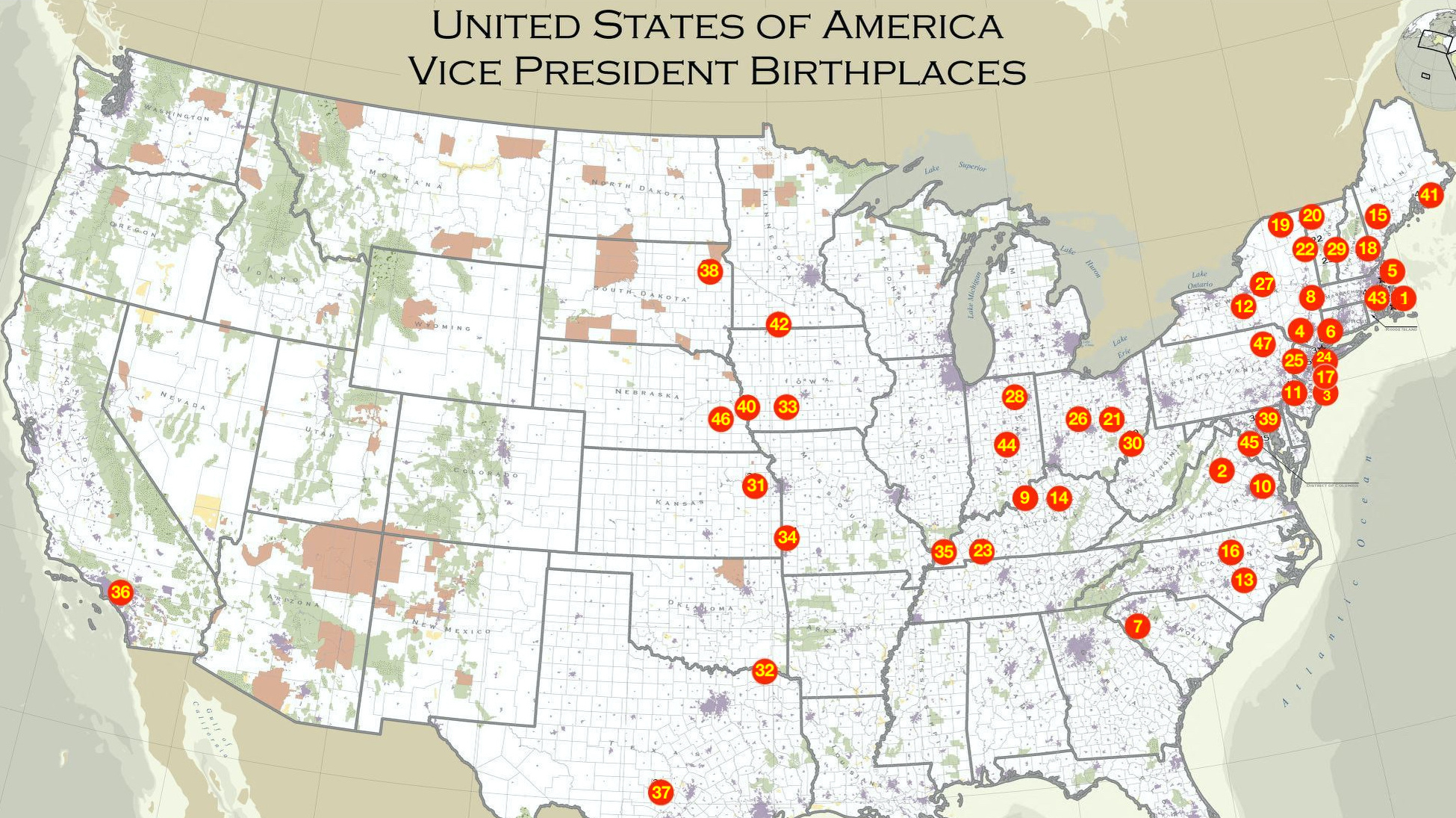

Map identifies 1,700 public memorials to the Confederacy

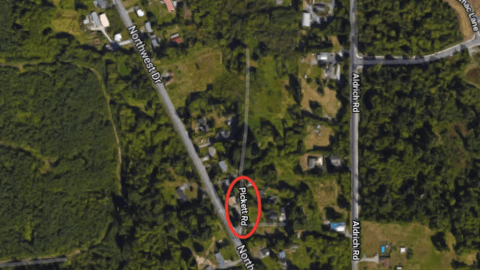

It’s easy to miss Pickett Road, a narrow dead-end off Northwest Drive in Bellingham, Washington. A few houses cluster near the junction with the main thoroughfare, which continues arrow-straight for miles in either direction. Pickett Road itself peters out barely a thousand feet due north, into a small clump of trees that separate it from Larrabee Road.

Unassuming as it is, Pickett Road has a unique distinction, a nationwide claim to fame – or infamy. Located just 15 miles south of the Canadian border, it’s revealed on this map as the northernmost Public Symbol of the Confederacy in the entire United States.

Most public symbols of the Confederacy are in the 11 states that seceded, but quite a few are outside the old South.

The map is featured on the website of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a non-profit organisation fighting for civil rights, and against white supremacist groups, since 1971. It’s part of a project taking aim at public memorials of the Confederacy, arguing that it’s time to stop honouring the ‘Lost Cause’ of the South – not because it was defeated, but because it was morally wrong.

The project, called ‘Whose Heritage? A Report on Public Symbols of the Confederacy‘, was initiated after the 2015 massacre of nine African-Americans at the Mother Emanuel church in Charleston. The shooter was a self-proclaimed white supremacist who on his website showed an affinity for the Confederate flag. The attack, almost 150 years to the day after the last shot in the Civil War, sparked a movement to finally remove that flag from public places throughout the South.

Soon after, South Carolina officials did remove it from the State House, where it had flown since 1961. The governor of Alabama ordered Confederate flags to be lowered near the state capitol in Montgomery. The movement quickly spread to other symbols. Memphis and New Orleans ordered the removal of Confederate statues. Elsewhere, the names of streets, parks, schools and even state holidays came under scrutiny.

To assist the re-examination, the SPLC started a comprehensive nationwide database of Confederate symbols – be they monuments and statues, flags or holidays, names of schools, highways or other public institutions. It’s the first such database, and it was recently updated.

According to the SPLC, 110 Confederate symbols have been removed since Charleston, but 1,728 still stand. And it’s high time they went: “Our public entities should no longer play a role in distorting history by honoring a secessionist government that waged war against the United States to preserve white supremacy and the enslavement of millions of people”.

Some of the SPLC report’s findings:

- Of the 772 remaining Confederate monuments and statues on public property (typically at county courthouses, town squares or state capitols), nearly half are located in just three states: Georgia (115), Virginia (108) and North Carolina (97).

- Most others are in the other eight states that seceded, with a smaller number in 13 further states, plus DC. Outside the old Confederacy, the states with the most memorials are Kentucky (24), Missouri (13) and West Virginia (9).

- No less than eight luminaries of the Confederacy have a statue in the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, DC. They include Jefferson Davis, its president, and Robert E. Lee, its most famous general.

- Confederate memorials outside the South include not one, but two Jeff Davis Peaks, in California and Nevada; the name of the city of Leesburg, Idaho (after Robert E. Lee); a Confederate Memorial Fountain in Helena, Montana; the Loyal Woman of the South Monument in Kansas City, Missouri; and busts of Lee and Stonewall Jackson in the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in the Bronx, New York City (still listed on the updated map, although their removal was ordered in 2017).

- About 100 public schools bear the name of prominent Confederates, most popularly Robert E. Lee (38), Stonewall Jackson (15), Jefferson Davis (11) and Nathan Bedford Forrest (8), the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Most are in the former Confederacy. An interesting outlier: Robert E. Lee Elementary in East Wenatchee, Washington. Two elementary schools in California named after Lee were renamed in 2016.

- Ten major U.S. military bases are named in honour of Confederate officers, including Fort Bragg in North Carolina, Fort Hood in Texas and Fort Pickett in Virginia.

- While most of the nearly 800 Confederate monuments and statues date from before 1950, 34 were dedicated after 2000.

- Most of the monuments removed after the Charleston massacre were in Texas (31), followed by Virginia (14), Florida (9), Tennessee (8), Georgia (6), Maryland (6), North Carolina (5) and Oklahoma (5).

The states with the highest number of Confederate memorials are Georgia, North Carolina and Virginia.

The map drawn up by the SPLC excludes thousands of monuments, markers, names and other tributes associated with battlefields, museums, cemeteries and other historical locations. However, it does include tributes to Confederate officers with distinguished careers before or after the Civil War, if they are currently remembered mainly for their role in the Confederacy.

One of them is Pickett Road. That name didn’t just accidentally turn up all in Bellingham, thousands of miles from the theatre of the war.

Yes, George Edward Pickett (1825-1875) was a general in the Confederate Army. But before his Confederate days, he was a career soldier in the U.S. Army. Straight out of the academy (graduating last in his class), Pickett saw action in the Mexican-American War, notably in the Battle of Chapultepec (1847), where he planted the U.S. flag on the castle, signalling the American victory.

George E. Pickett as a major general in the Confederate Army.

After the war, he transferred to what was then called the Washington Territory. In 1856, he commanded the construction of Fort Bellingham. His frame home survives; Pickett House is the oldest house in Bellingham. While stationed there, Pickett married Morning Mist, a Native American woman from the Haida tribe. She died soon after giving birth to their son.

In 1859, an American farmer on the disputed San Juan Island shot dead a pig belonging to the British-owned Hudson’s Bay Company. What ensued was the so-called ‘Pig War’, in which Pickett’s garrison prevented a British landing on the island.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Pickett left his posting in the Northwest to serve his native state of Virginia, which had joined the Secession. In his service to the Southern cause, he is remembered mostly for Pickett’s Charge, a futile offensive on the third and final day of the Battle of Gettysburg in which the Confederates suffered over 6,000 casualties against 1,500 for the Union.

Immediately after the Civil War, Pickett fled to Canada, fearing his wartime execution of 22 deserters would lead to prosecution. He returned to a year later, spending the remainder of his life as a farmer and insurance agent in Norfolk, Virginia.

Frequently asked why his famous charge failed, Pickett’s standard reply was: “I’ve always thought the Yankees had something to do with it”. After his death, Pickett was mythologised as the ‘perfect Southern gentleman-soldier’, not least by his widow’s books on her dead husband’s legacy.

Aerial image from Google Maps, other maps from SPLC/Google Maps, Picture of George A. Pickett found here atbattlefields.org.

Strange Maps #917

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.