Marchetti’s Constant: The curious principle that shapes our cities

Image: David Montgomery/CityLab

- The average commute, from antiquity to now: half an hour

- That’s Marchetti’s Constant, and it informs the growth of our modern cities

- But we’re stuck in traffic, and waiting for the next great leap forward.

Charles T. Harvey, president of the West Side & Yonkers Patented R.R., New York City’s first elevated railway, demonstrating in 1867 that a car would not fall off the track.

Image source: public domain

The curious constant

What do the citizens of ancient Rome have in common with those of modern Atlanta? The duration of their daily commute: an hour, at most. No matter whether we move on foot or by car, half an hour either way is about as long as we’re prepared to travel to and from our place of work.

That timeless truism is called Marchetti’s Constant, and it has a curious effect on the size of our cities. For as our modes of transport improve, the result is not that our commutes shrink, but that the distance between our homes and places of work increases. That, Jonathan English explains in a fascinating article over at CityLab, is why ancient Rome was tiny, and modern Atlanta is huge.

Even when it was the biggest city in the world, Rome was tiny by modern standards.

Image source: David Rumsey Map Collection courtesy Stanford University Libraries, CC-BY-NC-SA; image credit: David Montgomery/CityLab

When in Rome

For most of history, walking was the main way to get around cities. Since a mile (1.6 km) is about as far as you can walk in half an hour, that’s the maximum radius of a pre-modern city. Actually, ancient Rome is a good example: for several centuries at the start of the Common Era, it was the world’s biggest city. Yet its one million inhabitants were packed like Latin-speaking sardines into an area with a diameter of just two miles.

That’s about the same distance as from the Bastille to the Louvre, the extremities of medieval Paris. And, as Jonathan English remarks in his article, “the historic City of London is named the ‘Square Mile’ for a reason.” Up until the Industrial Revolution, urban growth meant cities got denser rather than bigger, leading to horrific levels of overcrowding. Escape to the country was a luxury available exclusively to the very rich — only they could afford both a rural mansion and an urban pied à terre.

The advent of modern transport brought the ideal of an escape from the city within reach of ever greater numbers of city-dwellers — but the effect was ultimately self-defeating: the growing size of the urban exodus meant they brought the city with them. But that change didn’t happen overnight: our current cityscapes are the result of centuries of experiments with transportation modes — always with Marchetti’s Constant as a yardstick for growth.

Medieval Paris was a bit smaller than Rome, a thousand years earlier.

Image source: Analyse Diachronique de l’espace Urbain Parisien: Approche Geomatique, Open Data Commons Open Database License 1.0; image credit : David Montgomery/CityLab

Philosopher on the bus

- The first public transit system was introduced in Paris in 1662 by none other than Blaise Pascal, the philosopher. His system of horse-drawn buses followed a set schedule, along fixed routes, for a distance-based fare. However, the system wasn’t much faster than walking, and collapsed after 15 years due to increased ticket prices.

- In 1830, Liverpool and Manchester were connected by the world’s first steam-powered public railway. Railways caught on quickly in major cities across the world. Moving people at speeds of 10 miles or more per half hour, railways allowed those who could afford it to live in “railroad suburbs” along the stops outside the city proper. Examples include Philadelphia’s Main Line suburbs and West London’s Stockbroker Belt.

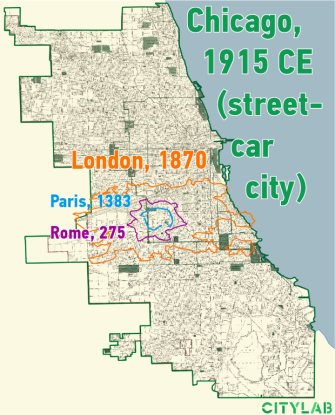

- From the 1880s, the introduction of electric trams and “safety bicycles” (i.e. not the high-wheeled penny-farthings) extended the commuter range of more lowly-paid workers. They now could travel in half an hour to 4 miles. This enlarged the potential size of cities from a diameter of 2 miles (i.e. 3 square miles) to a diameter of 8 miles (i.e. 50 square miles). Over the next decades, cities all over North America, and to a lesser extent Europe, adopted tram networks, and started sprouting new suburbs.

- Elevated trains, suspended above their straight streets avenues, further spurred the growth of American cities. These “el trains” and later subways, allowed the working class to live as far as 8 miles from their places of work. This allowed New York to spread out north to cover the entirety of Manhattan, for example.

London was one of the first cities to transcend the ancient limits of urban development.

Image source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, CC BY-NC-SA; image credit: David Montgomery/CityLab

Going Underground

- Lacking an American-style grid, London’s streets were not amenable to elevated trains. Because they couldn’t go up, they went under, and in 1863, the first London Underground line opened. The ‘Tube’ would soon become instrumental for spreading out the city over the surrounding counties, eventually annexing large parts of them. The county of Middlesex was almost entirely absorbed by Greater London (see #605), and disappeared off the map.

- In 1908, Henry Ford launched the Model T, the first mass-produced car. Despite its eager adoption by the middle classes, the automobile did not create huge urban growth in the 1920s and 1930s. That’s because the roads, built for non-motorized traffic, quickly choked up. Only after WWII would cars would start to transform cities — thanks to the introduction of expressways, which allowed people to move to and from cities with greater speed.

- After WWII, urban planners developed two competing methods to finally overcome the problem of inner-city overcrowding. The mainly European method, developed by Le Corbusier, was to concentrate people in free-standing high-rise towers, set in parkland ringing the old city centers.

The sprawl of ‘Chicagoland’ was made possible by the street car.

Image source: Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College Library; image credit: David Montgomery/CityLab

Welcome to Chicagoland

- The predominantly American method, developed by Frank Lloyd Wright, was based on the car, and proposed dispersing the population over a much wider area, on individual plots of land — a recipe for what has become the classic American suburb. This model allows for a 20-mile commute in 30 minutes, and that extends the metropolitan diameter to 40 miles. An “expressway city” can thus cover more than 1,250 square miles.

- In the 1970s, Wright’s model proved so successful that North America’s inner cities emptied out; except for its African-American inhabitants, kept out of the suburbs by various means of institutional discrimination. These days, the standard commute in North American metro areas takes around 26 minutes — about the same as that of the average citizen of ancient Rome.

- In the last few decades, the dispersal model has become the victim of its own success: traffic has multiplied, slowed down and become congested. Los Angeles, Atlanta, and other “expressway cities” have hit maximum capacity.

The dispersal model, the latest (and perhaps ultimate) phase of urban expansion.

Image source: U.S. Census; image credit: David Montgomery / CityLab

Sprawl ad infinitum?

So, what’s next after ‘stuck in traffic’? Jonathan English suggests three technological solutions, with varying degrees of feasibility:

- First option: high-speed rail. Downsides: very expensive, and facing “formidable ideological opposition” — at least in North America.

- Second option: self-driving cars. Downsides: still a pipe dream, will not improve road capacity, and may even increase congestion.

- Third option, and the most viable one: telecommuting. Working from home is already technologically feasible and holds “the greatest promise” for enabling Wright’s vision of the complete dispersal of population. But employers are resistant: they want their staff on-site, their physical presence the ultimate guarantee for productivity.

Here’s another idea: how about we reduce commutes and congestion by re-densifying the hollowed-out inner cores of our major cities? This too is neither easy or cheap, but the alternative is “sprawl ad infinitum,”and that, argues Jonathan English, has a huge environmental cost.

Images reproduced with kind permission of David Montgomery at CityLab. Read the entire article here on CityLab.

Strange Maps #988

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.