Nazi Treasure Maps

So there is a Nazi train hidden in a tunnel somewhere in southwest Poland. Or is there?

Ever since the end of the Second World War, the rumour of a train full of gold shunted away in a mountainside has floated around the countryside near the Lower Silesian town of Walbrzych. Like all good treasure stories, the Nazi Gold Train legend has a believable core and a fabulous prize, separated from each other by layer upon layer of conjecture and embellishment. And like most treasure stories, it remains totally unverified by factual proof (see also #63).

The legend goes something like this.

It’s the spring of 1945, and the Red Army is chasing the Nazis out of Eastern Europe. The fortified city of Breslau (now the Polish city of Wroclaw) is the Germans’ last best hope of stopping the Soviet march to Berlin. But Festung Breslau is crumbling fast. A train laden with gold and treasure slips out before the Soviets have the city completely surrounded. It heads west, but disappears somewhere between Breslau and the Czech border. Here is the Eulengebirge (the Owl Mountains), in which thousands of slave labourers have been carving out a vast and mysterious complex of subterranean tunnels and command centres.

The Nazis called the excavation of these caverns Projekt Riese (“Project Giant”), and their ultimate function is still a matter of debate. Construction began in 1943, when Allied bombers started flattening German cities wholesale. Riese could have accommodated a nuke-proof HQ for Germany’s military and political leadership, as well as various manufacturing facilities. But no plans for the complex, consisting of a number of separate, and perhaps interconnected sites, are known to have survived. The project, slated for completion in the fall of 1945, was abandoned in the general collapse of Germany’s Eastern Front. To date, only 10 percent of the tunnel complex has been uncovered, which of course helped fuel legends of hidden treasure.

Seven decades of fruitless treasure hunts later, many thought this was just another Eldorado story – too good to be true. But in 2015, two treasure hunters, a Pole and a German, defied the naysayers by filing a claim with the local council for a 10 percent finder’s fee for a 500-foot-long “armoured train carrying precious metals.” The legend is true! The train has been found! Or has it?

The essential ingredient of the very best treasure stories is the close-but-no-cigar twist. Ground radar scans have been released that seem to indicate the presence of a train-like object. But the exact location of the find, supposedly revealed in a deathbed confession, has not been made public, nor have excavations begun, out of concerns that the place might still be booby-trapped. Yet the evidence has convinced even Poland’s culture minister, who has now said he was “more than 99 percent certain that the train does exist.” As speculation on the whereabouts and contents of the Nazi train reaches fever pitch, some wonder whether it might contain the legendary Amber Room, stolen in 1941 by a German looting command from the Catherine Palace, south of Leningrad.

Whether and when the train will be revealed remains a mystery. Meanwhile, the Nazis have made another victim: a 39-year-old Polish treasure hunter fell to his death while looking for the subterranean chamber. The Nazi Gold Train story got another twist last Friday, when Polish explorer Krzysztof Szpakowski announced he had found two railway tunnels leading into a massive underground structure near Walbrzych, “the size of a large city,” which he identified as a previously undiscovered part of Projekt Riese.

Szpakowski based his find on evidence from first-hand witnesses and old documents, and by exploration with ground-penetrating radar and dowsers. He speculated that the tunnels, as yet unopened, could contain weapons and machinery — “but not a gold train.” The explorer’s press conference was hosted by the regional authorities in Walbrzych, who are now seeking state funds for the exploration.

Whether or not the train will actually be found, and be found to contain treasure, is still highly doubtful. While some treasure hunts occasionally turn up real treasure, the history of hunting for treasure is littered with false alarms, near misses, and dashed hopes.

Yet whatever the outcome, publicity around the train is sure to crank up the interest in hidden Nazi treasure, real or imagined. Just consider the sizeable overlap between conspiracy theorists, amateur historians, and anyone fascinated by the Nazis, and you have a huge cohort prepared to pore over obscure maps of the 1930s and ’40s, combing the countryside with their metal detectors for any signs of Nazi loot (1).

There must be plenty left to find. The estimates for works of art looted by the Nazis range from 100,000 to 200,000. Just two years ago, a cache of nearly 1,400 paintings was discovered in the Munich apartment of a man whose art dealer father had worked for the Nazis. Rural and out of the way of Allied bombers, the mountainous area around Walbrzych (before the war, the German town of Waldenburg) must have seemed ideal for hiding stuff. In fact, the Nazis established a depository for millions of valuable books stolen from various European libraries in Raciborz (in German: Ratibor), less than 100 miles southeast of Walbrzych.

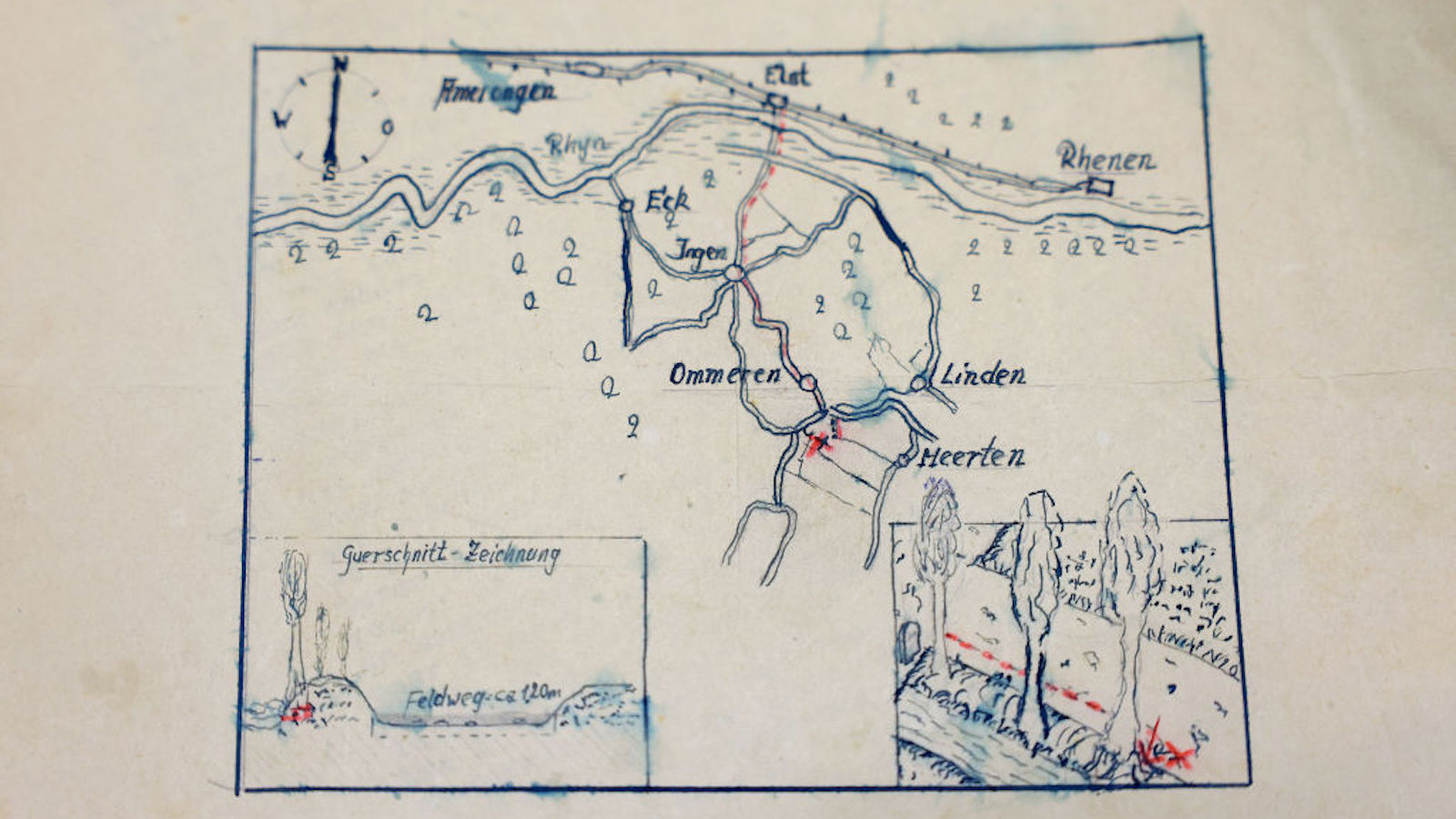

This map, while not the prettiest one ever, will get a lot of people excited. It shows the locations of presumed Nazi treasures yet to be found — in Alpine lakes, near castle ruins, on Danish beaches and even Latin America. Or maybe not. If nothing else, it sounds like a passable list of holiday destinations.

The most famous case of (presumed) Nazi treasure must be Lake Toplitz (Toplitzsee), high in Austria’s Dead Mountains (Totes Gebirge). During the war, it served as a Nazi naval testing station, so there’s probable cause for conducting treasure search, and numerous ones have taken place since the war. However, the closest thing to treasure ever to surface from the lake were millions of counterfeit pound sterling notes, produced for Operation Bernhard, an aborted plan to destabilise the British economy. Some insist that some kind of treasure still lurks in the darkest, most inaccessible depths of the lake.

The Toplitzsee’s reputation as treasure hoard made it onto the silver screen: in Goldfinger, James Bond handles a gold bar retrieved from the lake. Similar tales are told of the nearby Grundlsee and Seetalsee, and of the Chiemsee, the largest lake in neighbouring Bavaria, but searches have equally come up with nothing.

One of the most popular locations for Nazi treasure hunts is Deutschneudorf, on the Saxon side of the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge). It has been the presumed location of Adolf Hitler’s real grave, of the aforementioned Amber Room, and of large quantities of hidden gold and/or silver.

One of the more picturesque locations to hunt for Nazi treasure is the ruin of Castle Falkenstein — the highest castle in Germany. A steep, winding stone staircase is the only means to get to the top, where as yet no Nazi treasure has been found.

Close to Berlin, and even closer to Hermann Göring’s country retreat Carinhall, the Stolpsee is said by some to contain some of the valuables looted by Göring. Even the Stasi, the East German secret police, conducted searches for Nazi loot in the Stolpsee.

And then there is this Nazi treasure map, disguised as the score to a musical piece called the Marche impromptu. Dutch archaeologist Leon Giesen made the papers in 2013 by claiming the score to that song was actually a map to treasure buried in Mittenwald. Giesen believes that Hitler made Martin Bormann bury the gold and hide its location in the score. According to him, the music contains a diagram of train tracks that ran through Mittenwald in the 1940s, and the note Ende der Tanz (“end of the dance”) refers to the fact that the treasure is buried at the end of the railway’s buffer stops. But the area is in a military no-go zone, and the German defence ministry routinely refuses treasure seekers access.

Nazi treasure is not just presumed hidden in Germany. In Asaa, northern Denmark, the contents of three to five train cars are said to have been buried as early as the late summer of 1944. Again, plenty of treasure seekers, but no treasure.

Nor are rumours of Nazi gold limited to Europe. Some claim U-boats transported treasure to Argentina at the end of the war. If so, those involved did an excellent job hiding the stuff. Most high-ranking Nazis who fled to South America had to eke out their own living — Adolf Eichmann had a series of low-paying jobs before he landed a job at Mercedes-Benz Argentina. Josef Mengele worked as a carpenter and a printer, among other jobs.

More outlandish claims are of Nazi gold shipped off to a secret base in Antarctica — of course in the shape of an underground lair, the Nazi’s favourite type of fortification. But that takes us from the realm of treasure hunting to the even stranger kingdom of UFO spotting (see also #88).

Here’s another treasure map. The Lue map seems to be a collection of Masonic and/or Templar symbols, arranged possibly to indicate the location of 14 tons of gold buried somewhere in the U.S. Did we say 14 tons of gold? It gets better: 14 tons of Nazi gold.

This legend goes something like this:

In 1930s America, the Gold Reserve Act forbade the private possession of gold. The Lue Map, then, points to a stash of gold large enough to destabilise the U.S. economy (a variation on Operation Bernhard). The gold was smuggled into the U.S. via U-boats and moved by spy rings operating throughout the country to a single location — where it has remained ever since, after Nazi Germany’s collapse.

The Lue Map purports to be a cryptic key to this location, perhaps somewhere near the Four Corners in the southwest of the U.S. Or – another suggestion – it is an encoded description of the location of Fort Knox, the actual location of gold stockpiled by the U.S. government, drawn up by the aforementioned spy rings, for the benefit of their Nazi spymasters.

Warning: you’re only a few clicks away from clues of Japanese treasure buried in the Philippines, just waiting to be discovered.

Many thanks to Robert Capiot for sending in the link to this article in Die Welt, containing the first treasure map. The musical treasure map found here on Wikimedia Commons. The Lue map found here on TreasureNet.

Strange Maps #739.

Seen a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) Please note that unauthorised digging for treasure is illegal in most jurisdictions and as such not encouraged or endorsed by this blog.