The strange plan to fight nuclear bombs with giant rubber fortresses

- In 1950 as it does now, atomic war hung over the world as a Sword of Damocles.

- One optimistic solution: a string of rubber fortresses, to serve as early-warning posts.

- It’s unclear whether those forts were ever built. Perhaps they’re just really well hidden.

By a massive land grab, Moscow has revealed its hostile intentions. America and the wider West face the prospect of a prolonged conflict, the contours of which are not yet clearly defined. Nuclear war seems a lot closer than it was even a few months ago. Is this 2022? Yes, but it was also 1950, when the Iron Curtain was brand new, and the Soviet Union was still consolidating its grip on Eastern Europe.

Here’s one suggestion from the mid-20th century on how to prepare for nuclear conflict and emerge victorious. In the April 1950 issue of Mechanix Illustrated, Frank Tinsley wrote an article titled: “Rubber Fortresses for A-Bomb Defense.”

Rubber bubble fortress

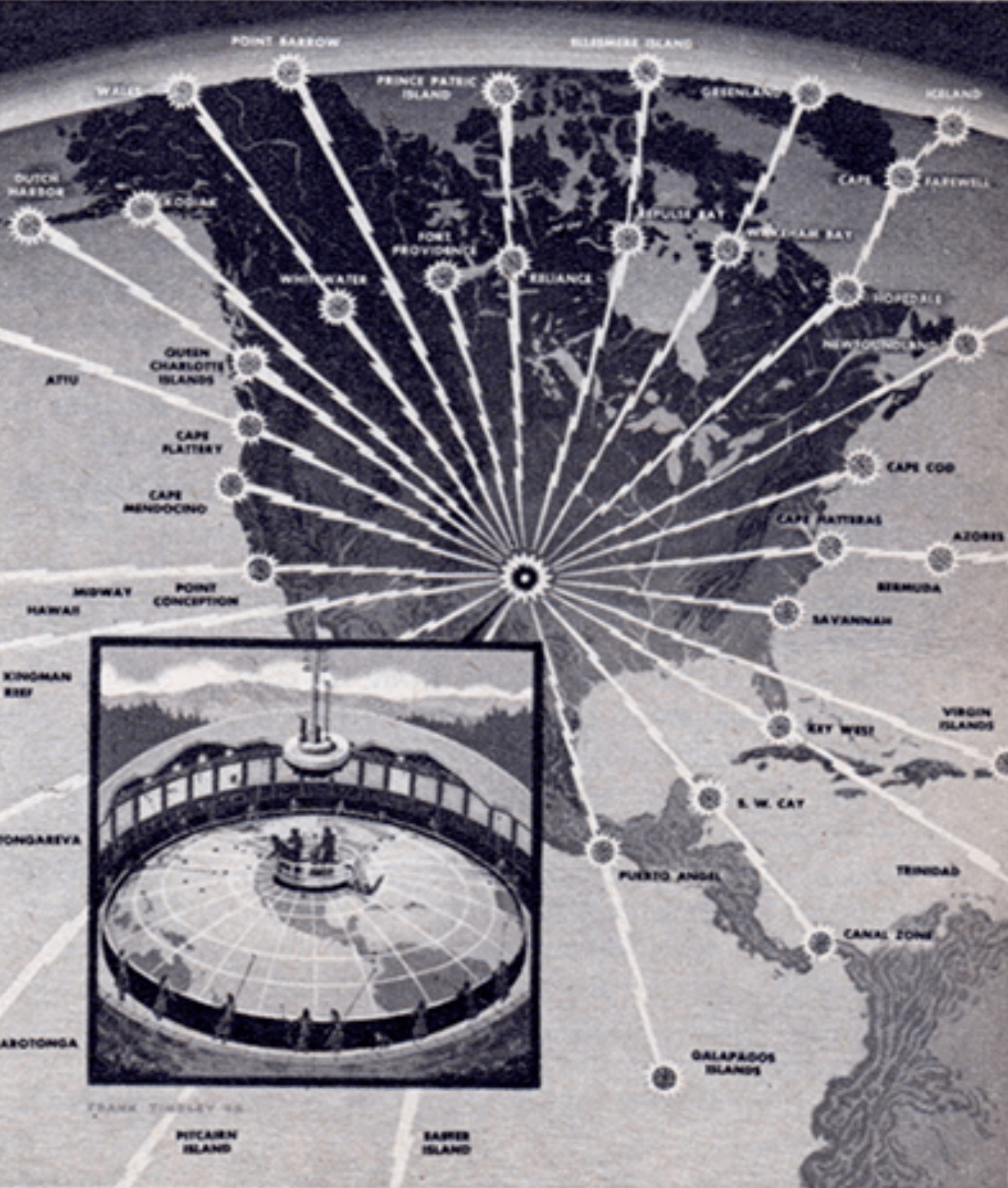

The article goes on to explain: “Can we avert an atomic Pearl Harbor? Yes, we can — with rubber bubbles! For a string of giant rubber bubbles, housing radar sentries, hidden in the icy peaks of America’s northernmost mountains, could be our first line of defense against any A-bomb attack.”

Why rubber? Because of Radome, a “revolutionary shelter of rubber and glass textile, developed by the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory Inc. for the Air Force research center at Red Bank, N.J.” “Radome” is a portmanteau of “radar” and “dome.” The term is still in use today, if less for a type of material than for a type of radar enclosure.

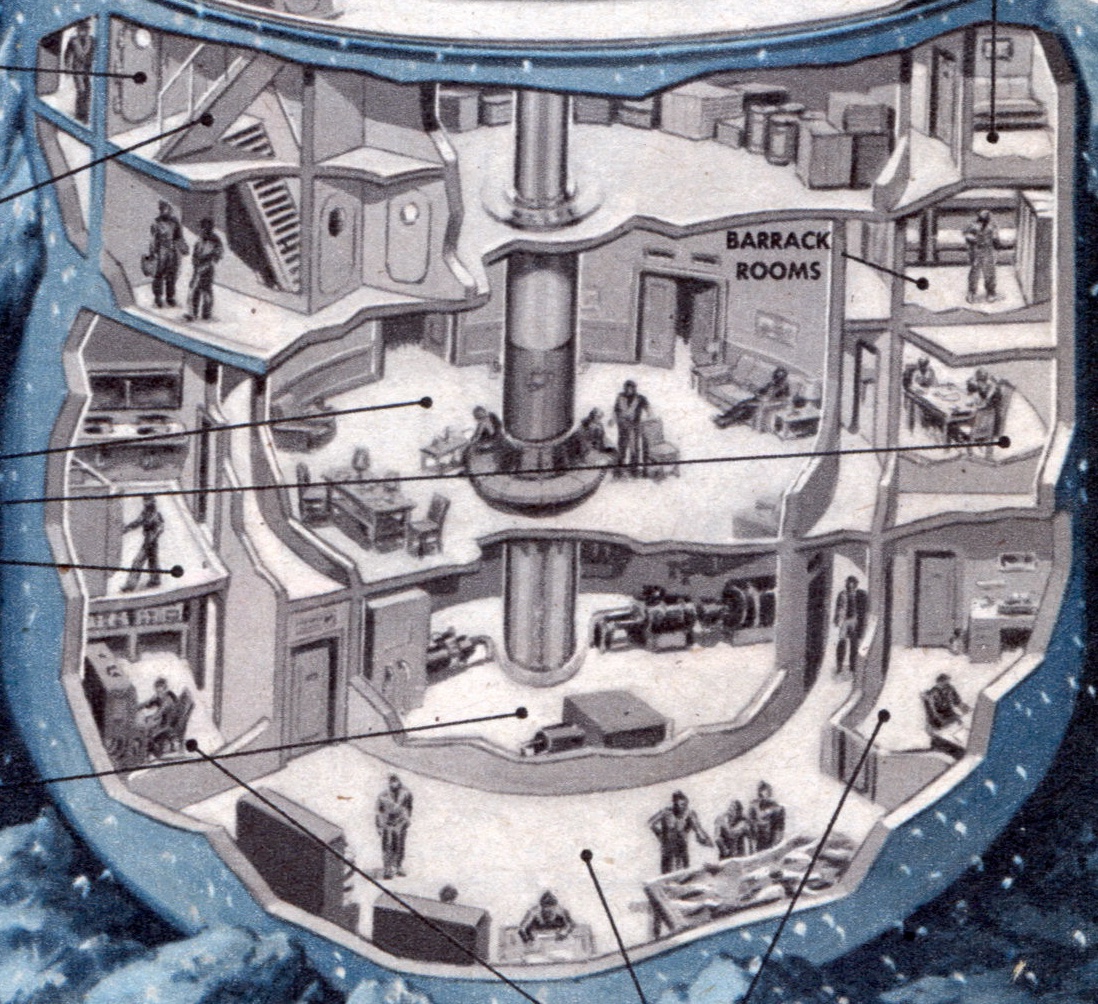

The article features a cutaway illustration, also by Tinsley, showing the insides of one of these rubber fortresses. On top, we see an inflated dome made of Radome. The spherical dome is camouflaged by air-inflated rubber rocks.

Revolving antenna fits into bomb-proof pit

Hiding beneath the dome is a 360°-revolving radar antenna, that can fully retract into a bomb-proof pit. A circular balcony at the foot of the antenna doubles as an indoor exercise track for the troops staffing the fortress. Deep below the antenna, there are spaces for the people and things that make the antenna work: barracks for the soldiers and slightly more spacious quarters for the officers. There is a lounge, a mess hall, and a library.

The lower floor hosts an engine room with diesel generators for power, lighting, and air conditioning, as well as the actual command center for the fortress. All living quarters are sealed off from the outside via an airlock stairway.

The stairs connect to the outside, where a helicopter landing pad is concealed from prying eyes by — what else? — inflatable rubber rocks. These are “fastened down in set patterns but easily removed to clear the way for flying operations.”

Could this be ice planet Hoth?

Outside, the snow is coming down in drafts. Considering the retro-futuristic appearance of the rubber fortress, it’s not hard to imagine that we are on the icy planet Hoth, in the Star Wars galaxy. While the personnel in this facility are far removed from the inhabited world, the illustration manages to suggest that inside, things could be quite comfortable, cozy even — unless and until the fatal alarm sounds, of course.

“These radar outposts could be the modern equivalent of the frontier forts” from the days in which the U.S. government clashed with Native Americans. Tinsley goes on:

“Miles apart in practically impassable wilderness, each must be a well-hidden, self-contained fortress, capable of guarding its precious equipment securely against any sneak attack. And sudden assault is just as sure as death and taxes. For if war comes again, the blinding of an enemy’s eyes will be the first step before wholesale atomic destruction!”

Where science met fiction

Mechanix Illustrated (1928-1984) was one among many magazines in mid-20th-century America where science met fiction, on the condition that the meeting of those two produced something wildly exciting. Truthfulness and feasibility were secondary concerns. So, while the article and illustrations strongly imply that these rubber bubbles were being considered as the first line of defense against an atomic sneak attack, nothing suggests that America’s military was ever serious about building a string of rubber fortresses across the northern edge of the continent.

Unless they just went ahead and did it, of course. How would we ever have known about them, cleverly hidden as they are below all those inflatable rocks?

Strange Maps #1148

Many thanks to Stijn Meuris for pointing out this map.

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.