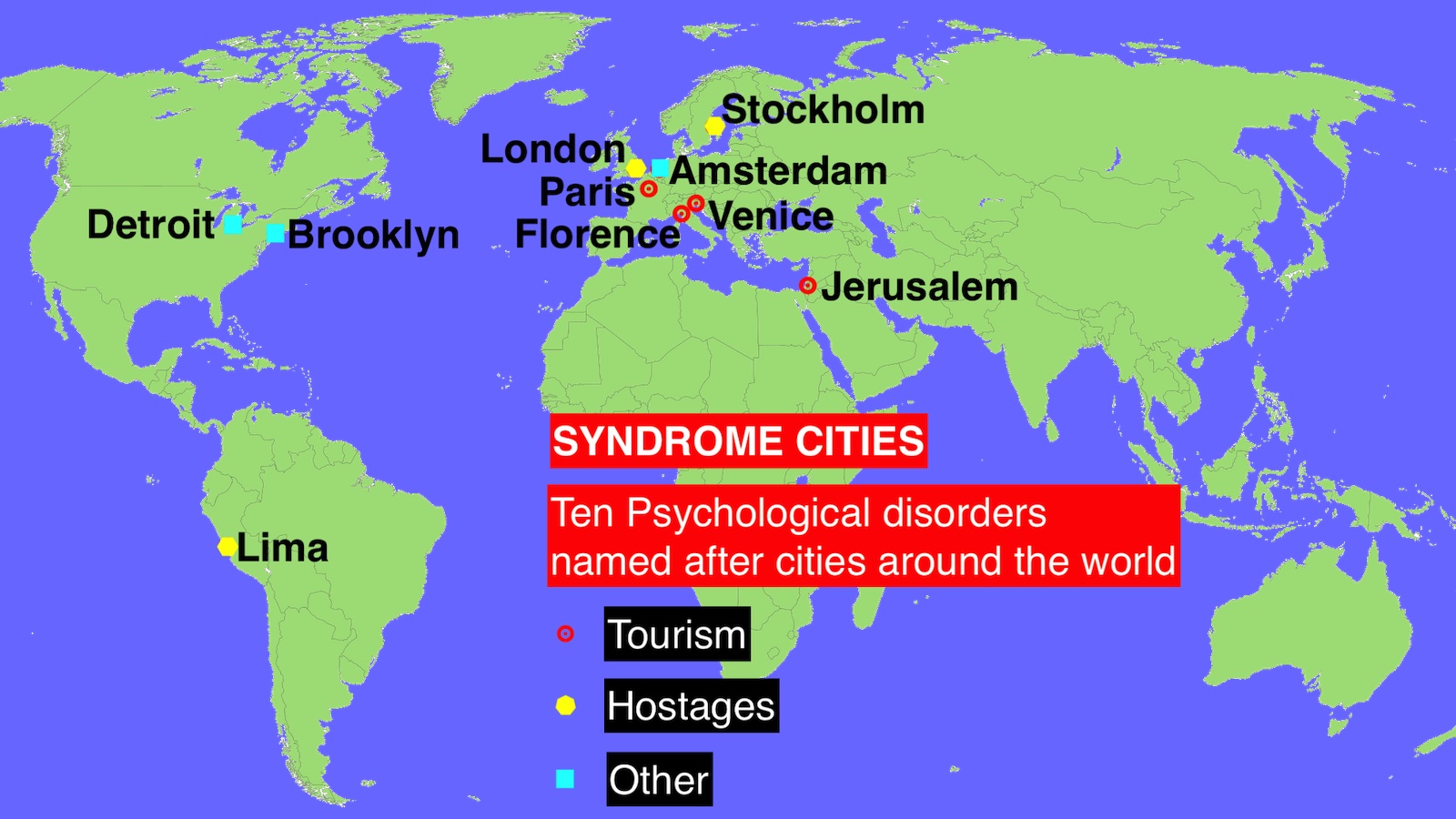

Twisted cities: 10 places synonymous with psychological disorders

- A psychological disorder is named after your town: a city marketing nightmare?

- Perhaps not. None of the places on this list seems to suffer from a syndrome-related lack of visitors.

- Having a disorder named after your city may even increase its appeal, however morbid.

Everybody knows Stockholm Syndrome, when hostages develop an attachment to their captors. But who knows its two opposites? Lima Syndrome is when the hostage takers start sympathizing with the hostages. And London Syndrome is when hostages become argumentative toward their captors — often with deadly results.

In all, ten cities around the world carry a unique burden: they have a psychological disorder named after them. In the September 2014 issue of Names, the journal of the American Name Society, Ernest Lawrence Abel listed and described them. He arranged them in three categories: four tourism-related, three linked to hostage situations, and three “other.”

Jerusalem Syndrome

First reported in the 1930s, Jerusalem Syndrome affects about 100 visitors every year. Of those, about 40 need to be hospitalized. Symptoms usually recede a few weeks after the visit. Uniquely religious in focus, this syndrome manifests as the delusion that the subject is an important Biblical figure. Previous examples include people who believed they were Mary, Moses, John the Baptist, and even Jesus himself.

Sufferers end up sermoning and shouting on the street, warning passers-by of the approach of the end times and the need for redemption. Often obsessed with physical purity, some will shave off all bodily hair, repetitively bathe, or compulsively cut the nails on their fingers and toes.

Jerusalem Syndrome affects mainly Christians, but also Jews, with some obvious differences. For instance: Christians mostly imagine themselves to be characters from the New Testament, while Jews tend to impersonate Old Testament figures.

Paris Syndrome

First reported in 2004, this syndrome mainly affects first-time visitors from Japan. On average, 12 cases are reported each year, mostly people in their 30s. Sufferers exhibit symptoms including anxiety, delusions (including the belief that their hotel room has been bugged or that they are Louis XIV, France’s “Sun King”), and hallucinations.

Why does Paris Syndrome mainly affect Japanese tourists? Perhaps it’s jet lag. Or it could be the jarring confrontation of the a priori ideal of Paris as exotic and friendly with the rather more abrasive nature of the city’s inhabitants. Or the high degree of linguistic incomprehension between the Japanese visitors and their Parisian hosts. Perhaps a bit (or rather, a lot) of all those things together.

The problem is important enough for the Japanese Embassy in Paris to maintain a 24-hour hotline, helping affected compatriots find appropriate care. Most patients improve after a few days of resting. Some are so affected that the only known treatment is an immediate return to Japan.

Florence Syndrome

First reported in the 1980s and since observed more than 100 times, this syndrome hits mostly Western European tourists between the ages of 20 and 40. American visitors seem less affected. The syndrome is an acute reaction caused by the anticipation and then the experience of the city’s cultural riches. Sufferers are often transported to the hospital straight from Florence’s museums.

Mild symptoms include palpitations, dizziness, fainting, and hallucinations. However, about two-thirds of the affected develop paranoid psychosis. Most sufferers can return home after a few days of bed rest.

This affliction is also known as “Stendhal Syndrome,” after the French author who described the phenomenon during his visit to Florence in 1817. When visiting the Basilica of the Sacred Cross, where Machiavelli, Michelangelo, and Galileo are buried, he “was in a sort of ecstasy… I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations… I walked with the fear of falling.”

Venice Syndrome

Rather more morbid than the previous conditions, Venice Syndrome describes the behavior of people travelling to Venice with the express intention of killing themselves in the city.

Just between 1988 and 1995, 51 foreign visitors were thus diagnosed. The subjects were both male and female, but the largest group came from Germany. Possibly, this is due to the cultural impact of Death in Venice, the novel by German writer Thomas Mann, which was subsequently turned into a film. However, others within the cohort came from the U.S., Britain, and France, as well as other countries. In all, 16 succeeded in their suicide mission.

According to research conducted into the phenomenon — mainly by interviewing the 35 survivors — it seemed that “in the collective imagination of romantic people, the association of Venice with decline and decadence was a recurring symbol.”

Stockholm Syndrome

Three related city syndromes are linked to hostage situations, the most famous one in the Swedish capital. According to the article in Names, about one in four of those abused, kidnapped, or taken hostage develop an emotional attachment or a sense of loyalty toward their captors or abusers. Some even start to actively cooperate, crossing the line from victim to perpetrator.

This syndrome was first named following a bank robbery turned hostage situation in Stockholm in the summer of 1973. The robbers held four bank employees hostage for six days. The hostages were strapped to dynamite and locked up in a vault. After the negotiated surrender of the robbers, the hostages said they felt more afraid of the police, raised money for the defense of the captors, and refused to testify against them. One of the hostages even became engaged to one of her captors.

In 1974, the newly minted term was used in relation to Patty Hearst. Abducted and abused by the Symbionese Liberation Army, the teenage heiress nevertheless “switched sides,” and eventually helped them rob a bank.

Lima Syndrome

Less well known, Lima Syndrome describes the exact opposite of Stockholm Syndrome — that is, the captors develop positive attachments to their hostages. The name refers to a crisis in the Peruvian capital in December 1996, when members of the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement took 600 guests at the Japanese Embassy hostage.

The captors became so empathetic toward the guests that they let most of them go within days, including high-value individuals such as the mother of the then-president of Peru. After four months of protracted negotiations, all but one of the hostages were freed. The crisis was resolved following a raid by special forces, in which two hostage takers and one commando died.

London Syndrome

London Syndrome is described as the opposite of both Stockholm and Lima Syndromes, in that it involves the development of negative feelings of hostage takers towards their hostages. In fact, London Syndrome most accurately describes a situation whereby hostages provoke their own death at the hand of their captors by annoying, debating, or challenging them, or by trying to escape.

The name comes from the 1981 siege of the Iranian Embassy in London, during which one of the 26 hostages repeatedly argued with his captors, despite the pleading of the others. When the hostage takers decided to kill one of their hostages to further their demands, they shot the argumentative one, throwing his body out into the street.

The execution prompted an armed intervention by police forces, during which more hostages were killed.

Amsterdam Syndrome

The three syndromes in the “other” category are only metaphorically related to the city that they are named after.

Amsterdam Syndrome refers to the behavior of men who share pictures of their naked spouses, or of themselves having sex with their spouses, without their consent. The term is believed to reference Amsterdam’s Red Light District, where prostitutes are on display behind windows.

This name was coined by a sexologist at the University of La Sapienza in Italy and first publicized at a 2008 conference of the European Federation of Sexology in Rome. At the time of writing the paper, the syndrome had not been properly examined. It was primarily used to describe Italian men, who posted said images on the internet.

Brooklyn Syndrome

This term was coined during World War II by Navy psychiatrists, who noticed certain behavioral characteristics and patterns in a segment of the men recruited into military service. At first, these traits were believed to be a psychopathology. Eventually, because they occurred with such frequency, they were recognized as related to the places of origin of the men involved: cities where, due to specific cultural circumstances, the male persona naturally gravitates toward being overly argumentative or personally combative.

Detroit Syndrome

Detroit Syndrome is a form of age discrimination in which workers of a certain age are replaced by those who are younger, faster, and stronger, not to mention endowed with new skills better suited for the modern workplace. The syndrome, reported in 2011, gets its name from Detroit, and more specifically from its reputation as a manufacturing hub for automobiles, in which newer models would replace the older ones on a regular basis.

Check out the full article in the June 2014 issue of Names, the quarterly journal on onomastics by the American Name Society.

Did the paper miss any other “city syndromes,” or have new ones been named since? Let us know.

Strange Maps #1127

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.