Maybe Ukraine should claim some of Russia’s land, instead

- Be careful with territorial claims, Mr. Putin: that sword has two edges.

- Russia has designs on Ukraine, but those can easily be reversed.

- A century ago, Ukrainians founded a short-lived state on the Pacific.

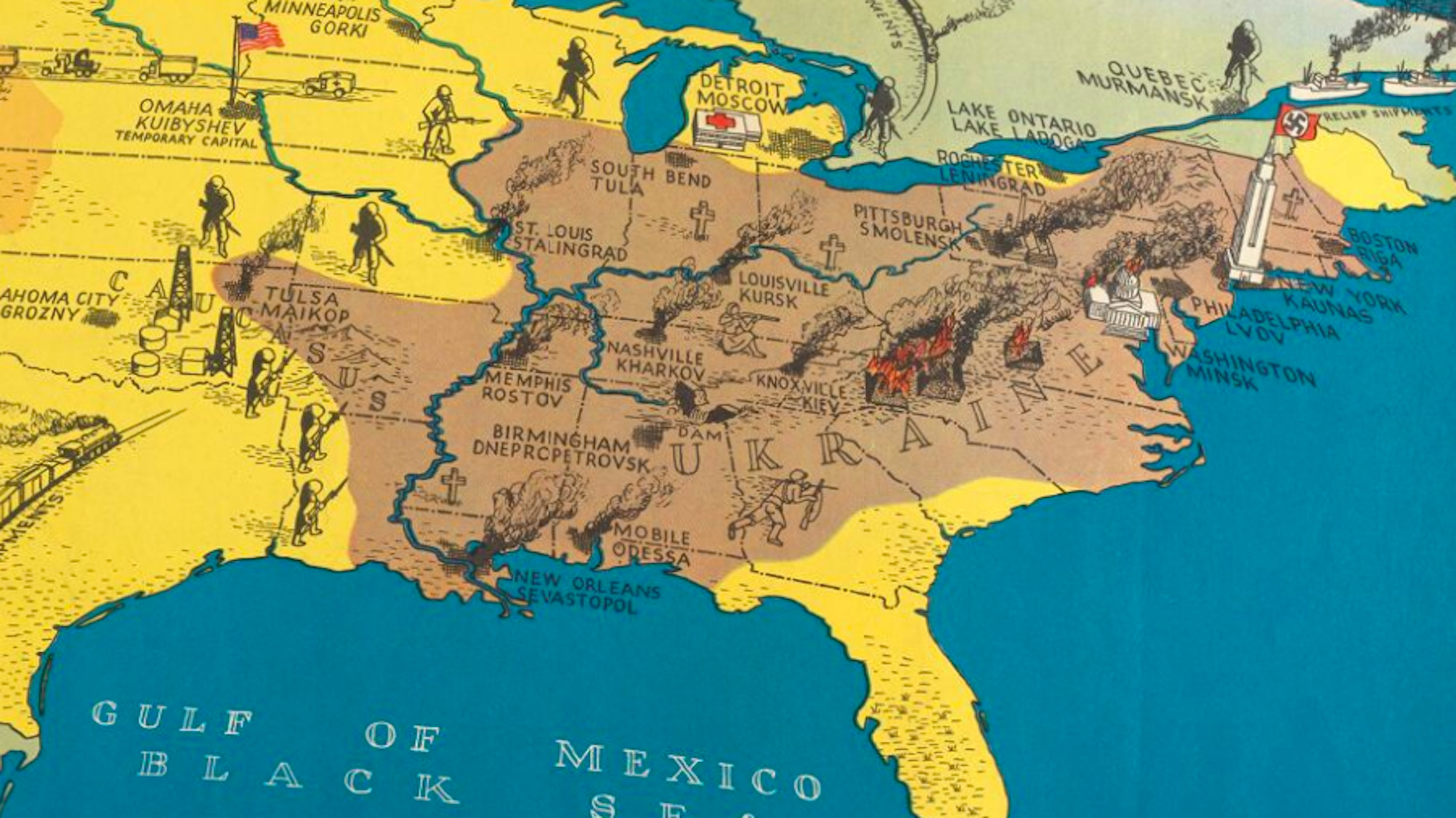

So, Russia has historical rights in and territorial claims on Ukraine? Careful how you wield that sword, Mr. Putin. It has two edges. It turns out that large and surprisingly far-flung parts of Russia have a long and rich Ukrainian history. Wouldn’t it be a shame if someone started waving that past around, feeling aggrieved about the current deficit of Ukraine-ness in those areas?

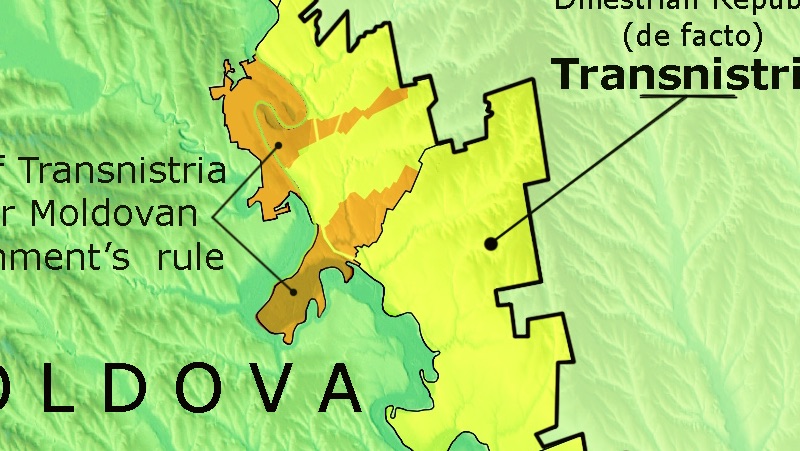

(Please note this is not a serious plea for Ukrainian irredentism. The world would benefit from less historic bitterness and fewer territorial claims – not more. Realizing that everyone has a supposedly more glorious past to look back upon might help rebalance one’s own sense of historical grievance, territorial and otherwise).

For centuries, Ukrainians have migrated into Russia, leaving their mark on that country individually — as high-ranking clergy, leading scientists and artists, and successful traders — and collectively, as settlers of Russia’s most thinly-populated lands.

The Ukrainians were not the only settlers. Obviously Russians themselves moved into these areas, but the authorities also invited other ethnic and religious minorities, including groups later known as the Volga Germans and the Hutterites — who, as a matter of fact, settled in Ukraine itself (see Strange Maps #1118).

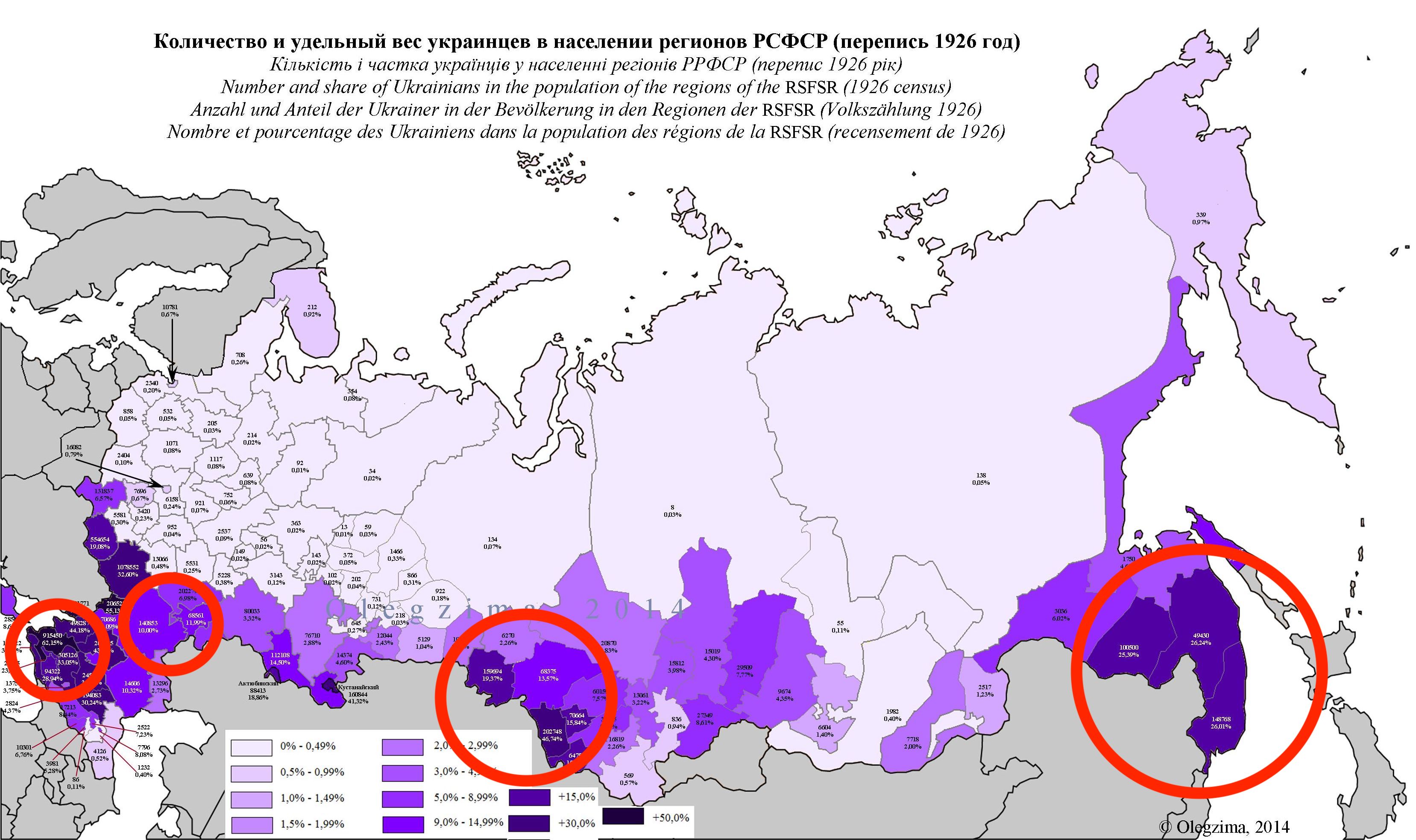

Attracted by the promise of free land, Ukrainians first migrated to areas close to Ukraine proper, such as Kuban, an area bordering the Black Sea, between Crimea and the Caucasus. Gradually, Ukrainian settlers moved further east, eventually all the way to the Pacific, where the Russian Empire bordered China and Japan. Russia’s 1897 census counted 22.4 million Ukrainian speakers inside the Russian Empire, of which 1.2 million lived outside what was then considered Ukraine. Of these, just over a million lived in the European part of the Empire, with more than 200,000 in the Asian part.

Over time, many Ukrainians assimilated into the Russian majority. However, in many areas, especially where they had founded their own villages, Ukrainians formed majorities and managed to maintain their own language and traditions.

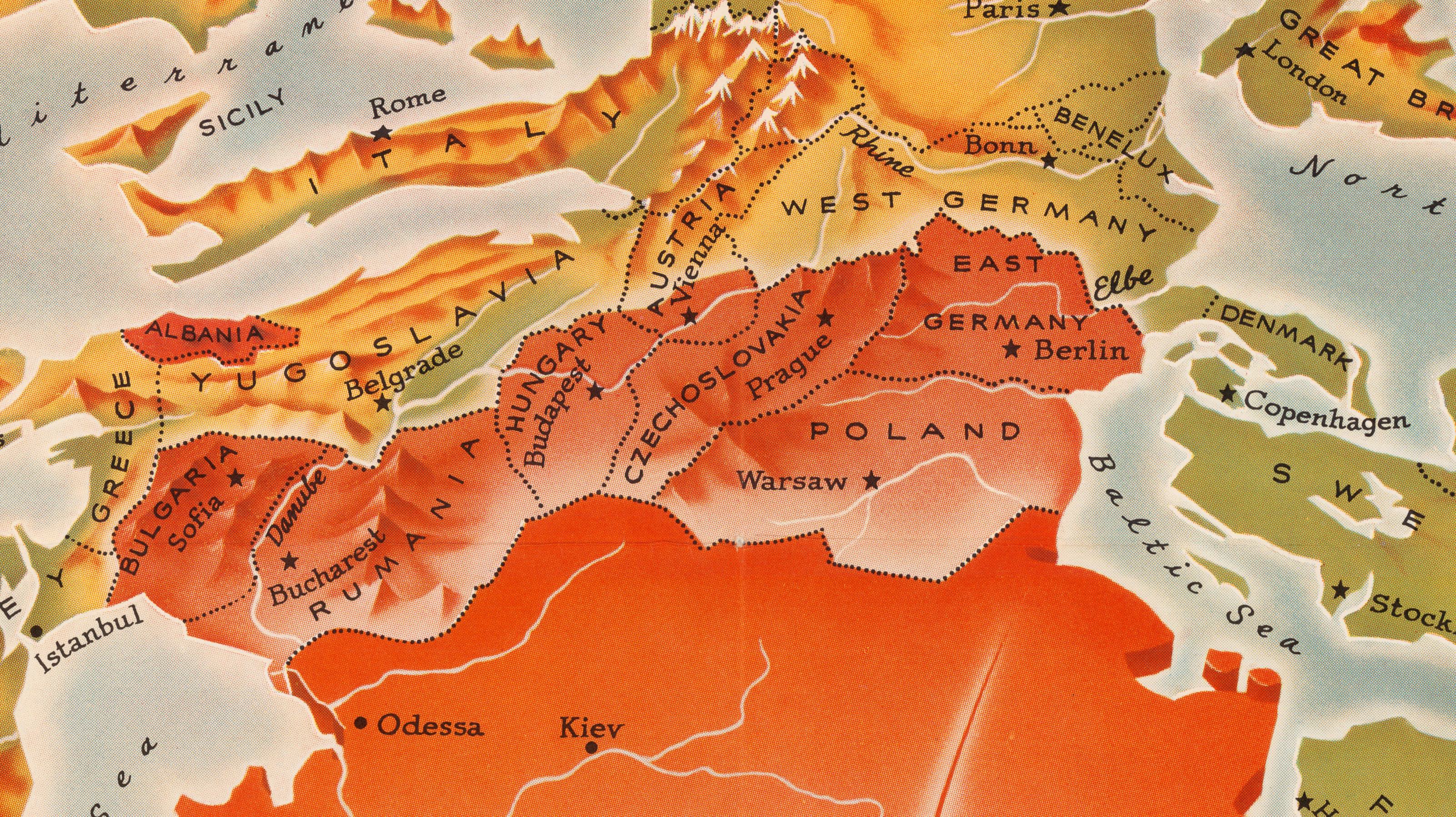

Four areas stand out, each named after a color:

- Raspberry Ukraine (a.k.a. Malinovy Klyn, or the “Raspberry Wedge”)

The aforementioned zone in Kuban was settled from the end of the 18th through the 19th centuries by Ukrainian cossacks and peasants. A short-lived Kuban People’s Republic (1918-20) sought to federate with Ukraine, also briefly independent in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917. As late as the 1930 census, 62% of the local population identified as Ukrainian. The area has now largely been Russified.

- Yellow Ukraine (a.k.a. Zhovty Klyn, or the “Yellow Wedge”)

From the second half of the 17th century onward, Ukrainians founded many settlements in this area, named after the yellow steppes along the mid- to lower-reaches of the Volga river. Ukrainian settlement was especially pronounced around Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, and Samara. Although some areas still have a marked Ukrainian character, settlement by Ukrainians in this area was mostly too dispersed and intermingled with other settlers for them to form a significant independent political force after 1917, as they managed in other “wedges.”

- Grey Ukraine (a.k.a. Siry Klyn, or the “Grey Wedge”)

This is an area around the western Siberian city of Omsk, currently divided between southern Siberia and northern Kazakhstan. The area was settled by Ukrainians from the 1860s. A total of more than 1 million of them arrived before 1914. Right after the October Revolution of 1917, attempts were made to establish a Ukrainian autonomous region.

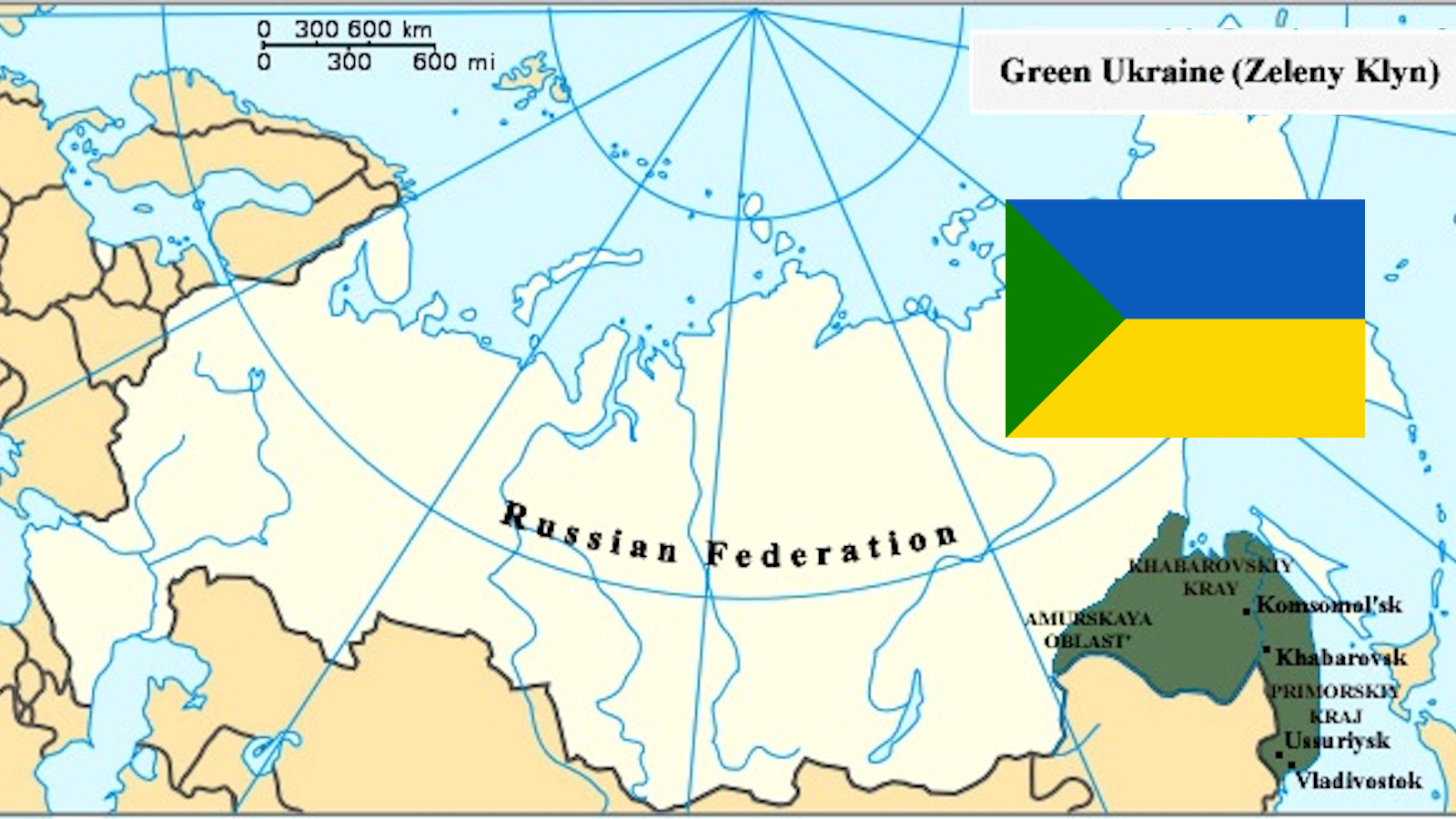

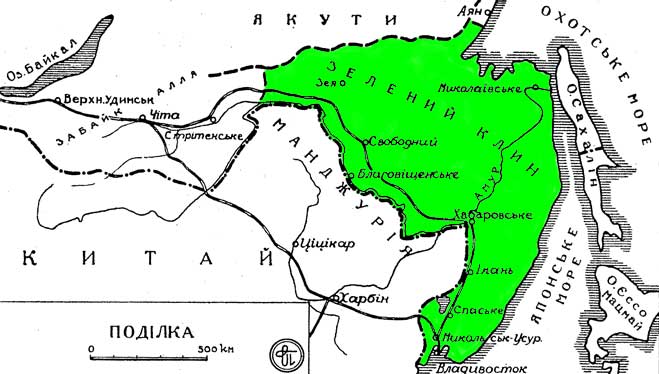

- Green Ukraine (a.k.a. Zeleny Klyn, or the “Green Wedge”)

Perhaps the most improbable — because it was certainly the most distant of the “color Ukraines” — was Green Ukraine, located in the furthest southeast of the Russian Empire, jammed in between China and the Pacific Ocean and centered on the Amur River. Yet by some estimates, the region counted up to 70% of Ukrainians at the start of the 20th century.

In June 1917, the First All-Ukrainian Congress of the Far East, held near Vladivostok, demanded from Russia’s new interim government education in Ukrainian and autonomy for Ukrainians. The meeting also established a Rada, Ukrainian for “council”.

A second Congress, held in Khabarovsk in January 1918, proclaimed Green Ukraine to be part of the Ukrainian state — despite the minor inconvenience that the motherland was a continent away. At a third Congress in April of that year, the delegates approved the creation of a Ukrainian state with access to the Pacific.

The Ukrainian Republic of the Far East was officially proclaimed on April 6, 1920. But “Green Ukraine” did not survive for long. In October 1922, Communist forces invaded the territory. The last holdouts were defeated in June 1923.

Almost a century on from the demise of Ukraine-on-the-Pacific, it seems improbable that any of the aforementioned color wedges comes back to create a tit-for-tat secessionist headache for Mr Putin. Because of their cultural and linguistic proximity to Russians, Ukrainians tend to assimilate into Russian society after a generation or two at most.

Nevertheless, Ukrainians remain one of the largest ethnic groups inside Russia: 1.9 million, or 1.4% of the total population of Russia, according to the 2010 census. Due to recent migration, also caused by the war in Ukraine, the current number is likely much higher. A recent poll indicates half of all Ukrainians have relatives living in Russia.

For more on the many short-lived states that sprang up after the 1917 Russian Revolution, check out Strange Maps #896.

Strange Maps #1129

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.