In 1930, Picasso Had a Vision of Manhattan as a Four-Layered Traffic Lasagna

First there was that bizarre diagram of what looks like a giant spaceship buried beneath central London. Who made this weird, wonderful map?

The same hand, it turns out, that produced two captivating visions of Manhattan: one of its concrete canyons filled up with a multi-layered traffic lasagna, another showing a boulevard weaving, spaghetti-like, over and under a bunch of avenues.

Strange maps of a never-realised future. Made more intriguing by that name and job title: Picasso, architect. Did the great painter have a now-forgotten architectural interval some time between his Blue Period and his Surrealist Phase?

But no, this is not Pablo. Meet Renzo Picasso (1880-1975), no relation. This Picasso is a Genoese architect, engineer and inventor; an urban enthusiast, dreamer and planner. His legacy is obscured by being not only the other Picasso, but also the other Renzo: students of modern architecture know about Renzo Piano (b. 1937), another Italian master-builder – coincidentally also hailing from Genoa.

Piano designed such landmarks as the New York Times Building in New York and the Shard in London. In contrast, the other Renzo’s architectural schemes never made it off the drawing board, the beautiful maps and plans he drew their only tangent with reality.

Renzo Picasso first visited New York in 1911, and was awestruck by its sky-scraping architecture. He began producing architectural observations and comparisons, and eventually started drawing plans for the future, with particular attention to transit systems and traffic infrastructure. Not just for New York, but also for other cities, including his native Genoa, for which he designed a number of New York-style grattanuvole (‘cloudscratchers’).

None of Picasso’s grand schemes came to fruition. It’s easy to thus label them ‘utopian’. But is it so far-fetched to imagine Genoa’s waterfront embellished by his 50-story Torre della Pace (‘Peace Tower’)? And would his plan for four-layered transit arteries not have solved the traffic gridlock in New York and other cities?

Perhaps the dismissive ‘utopian’ epithet can be reserved for Picasso’s more patently unworkable plans, the ones for military vehicles. At the end of World War I, then-lieutenant Picasso designed two fantastic contraptions: the motovol, a winged motorcycle; and the auto-scafopattino, a motorised canoe fitted with artillery.

The vehicles are reminiscent of some of Da Vinci’s designs, or of the creations of Belgian artist Panamarenko, who builds vehicles that can conquer sky and space – on the condition that they are never tested. As engineering, they would fail. As art, they are vehicles for contemplating flight.

Perhaps that is the right attitude to appreciate Picasso’s urban designs: wistful what-ifs rather than serious proposals. The passage of time seems to have left us with no other option.

Piccadilly Circus Tube Station (1929) – drawn to coincide with the opening of the new circular booking hall, this diagram shows Piccadilly Circus Tube Station from a subterranean perspective, providing a three-dimensional view of the complex of entrances, hall, escalators and tube lines. The buses are shown floating on the invisible surface. The statue of Eros is labelled as a ‘world centre’.

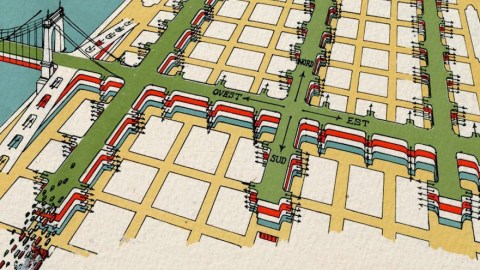

American Multiple Highway (1930) – Manhattan’s main arteries are overlaid with four layers of traffic. The top layer is reserved for trains, the one beneath for express car traffic, the third one for parking space and the ground level for local traffic.The Multiple Highway would extend off Manhattan, across the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, and through the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels.

Crosstown Boulevard (1929) – diving under every other avenue, this boulevard provides a speedy connection between the east and west sides of Manhattan. Note the ‘aero-garages’ at the end of airplane runways pasted high up along the city’s straight-line street grid.

Genoa Transit System (1911) – already inspired by New York, this never-realised scheme divides long-distance (red) from local traffic (green), and individual vehicles (surface) from trains (underground). Multi-level walkways provide access.

Torre della Pace (1917). Note the Lady Liberty-like figure on top.

Motovol and auto-scafopattino (both patented 1918)

All images from the Renzo Picasso Archive. See also its presence on Facebook.

Strange Map #790

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com!