Coming to a night sky near you: The Perseid meteor shower!

One of the best—if not THE best—meteor showers of the year is about to kick into high gear, and the timing is perfect; with the new moon occurring at exactly the same time as the Perseid meteor shower, this show could be spectacular at 60-70 meteors per hour and sometimes double or even triple that.

While they can appear anywhere overhead, most will show up in the north/northeast sky near the constellation Perseus—hence the name.

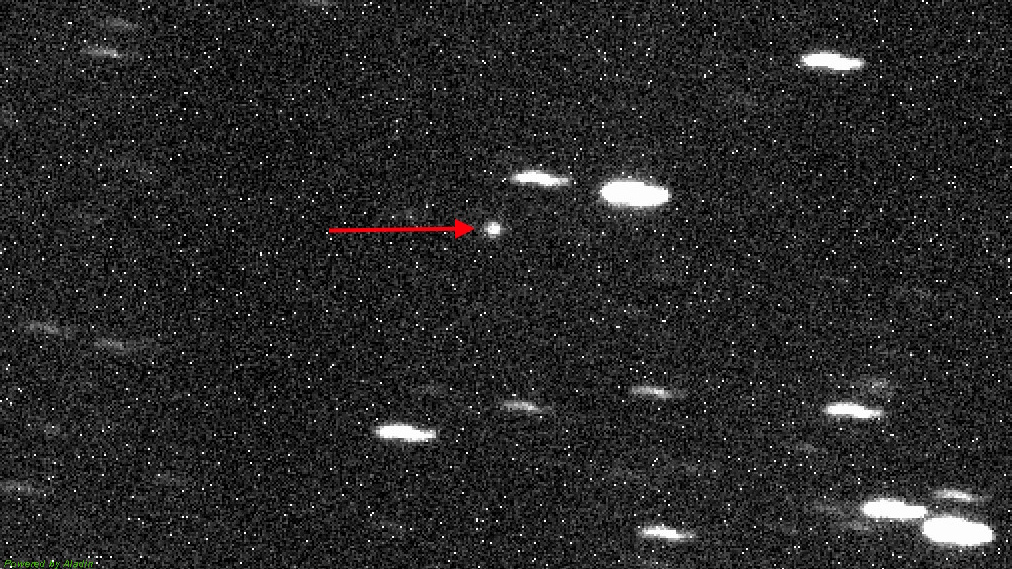

Image: NPS/JPL-Caltech.

The comet Swift-Tuttle, first recorded in 1862 with its most recent pass in 1992, is responsible for this display. This year, the peak is night/morning (think 1:00 or 2:00 a.m.) of August 11 and the early morning hours of August 12 and 13 as well. The shower actually began July 17 and lasts until August 24, so you might see a few here and there on any of those nights, but the upcoming dates will give the best chance of seeing them.

So what, exactly, are they?

Meteors (also known as shooting stars) are bits and pieces of comets and asteroids that enter the solar system—ice particles, dust, tiny rocks—and slam into Earth’s atmosphere at tens of thousands of miles per hour.

A Perseid meteor streaks across the sky over the Lovell Radio Telescope at Jodrell Bank on August 13, 2013 in Holmes Chapel, United Kingdom. (Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Meteors are no larger than a grain of rice, while meteorites can be larger-size rocks, even as massive as 60 tons. Those are the ones responsible for the huge, night-turns-to-day displays that can be accompanied by a loud BANG, and sometimes, send pieces raining down upon the Earth.

Meteor showers are largely predictable and they occur around the same time every year, while their larger cousins are pretty random. This is because the Earth passes through each flotsam/jetsam stream that is left behind as it makes its way around the sun each year. They’re at specific points in Earth’s orbit, so that’s why you can plan your meteor-watching calendar around certain times of year.

It’s difficult to “see” just where they are in the atmosphere because we’re down below them, but they usually become visible 30 to 60 miles above the Earth’s surface.

So, weather permitting, lay out a nice flat chair so you’re not craning your neck, and just plan on viewing with the naked eye, unless you’re a photography nut who can figure out all of the settings to capture such things; if that’s the case, aim for a wide swath of the Northern night sky, rather than specific points.

And don’t forget to make a wish.

Or 70.