First gene-edited babies born in China, scientist claims

(Photo: ANNE-CHRISTINE POUJOULAT/AFP/Getty Images)

- The claim is unsubstantiated as of yet, but if true it would mark a historic moment in science and ethics.

- The scientist claims to have edited a gene that controls whether someone can contract HIV.

- Many say gene-editing is unethical, or that its technology is too premature to be used responsibly.

A chinese scientist claims to have helped create the world’s first genetically edited human babies, a development that would be both historic and highly controversial if true.

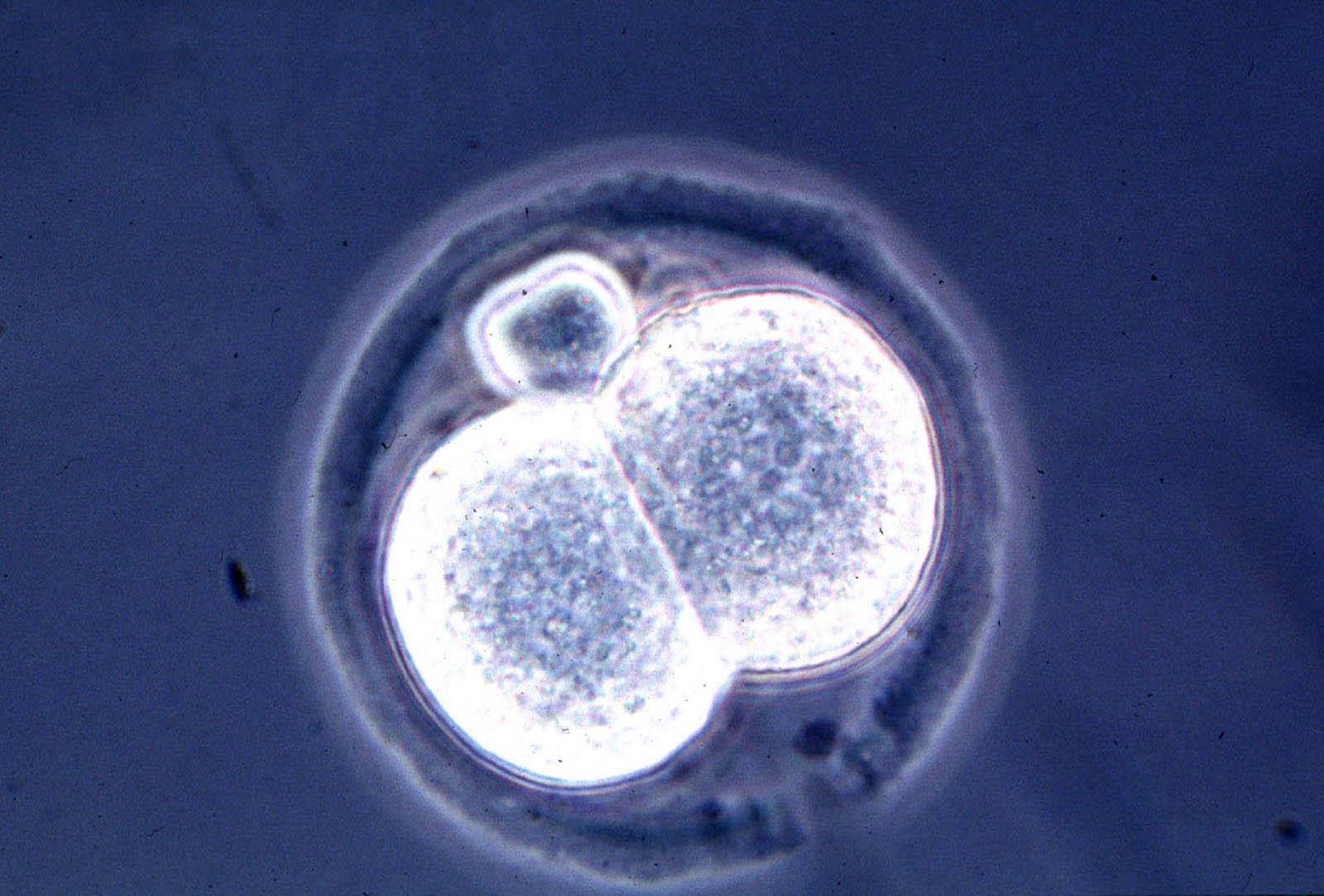

The scientist, He Jiankui of Shenzhen of the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China, said he and his colleagues used a gene-editing technique known as CRISPR to modify the embryos of twin girls born this month. The team reportedly made changes to one-day old embryos in a gene called CCR5, which enables HIV to enter and infect immune system cells. These changes supposedly made it impossible for the girls, whose father is HIV-positive, to contract the virus, which causes AIDS.

“When Lulu and Nana were just a single cell, this surgery removed a doorway through which HIV enter to infect people,” He says in one of several videos the scientist posted online, adding elsewhere that analyses confirm that both babies were born healthy. “No gene was changed except the one to prevent HIV infection…This verified the gene surgery worked safely.”

A questionable and controversial claim

Some doubt He’s claim, which remains unsubstantiated in the absence of confirming evidence or data published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. Several scientists who reviewed He’s materials told The Associated Press that the findings are incomplete or don’t necessarily mean it’s impossible for the children to contract HIV.

The Southern University of Science and Technology said in a statement it was unaware of the project and that He potentially “seriously violated academic ethics and standards.” The university plans to investigate.

Even if proven true, many scientists argue that using gene-editing technology in this way, at this stage of development, would be highly unethical.

“If true, this experiment is monstrous,” Julian Savulescu, a professor of practical ethics at the University of Oxford, told The Guardian. “The embryos were healthy. No known diseases. Gene editing itself is experimental and is still associated with off-target mutations, capable of causing genetic problems early and later in life, including the development of cancer.”

Gene-editing, used in this way, is illegal in the U.S. and many other countries because of the currently unforeseeable risks it poses to future generations.

“This is far too premature,” Dr. Eric Topol, who heads the Scripps Research Translational Institute in California, told The Associated Press. “We’re dealing with the operating instructions of a human being. It’s a big deal.”

In addition to safety concerns, others raise ethical questions about creating “designer babies”—which would be the genetic modification of embryos not only to prevent disease, but also to produce taller, smarter, or better-looking children.

Still, He said he was prepared for the blowback.

“I understand my work will be controversial,” he says. “But I believe families need this technology. And I am will to take the criticism for them.”