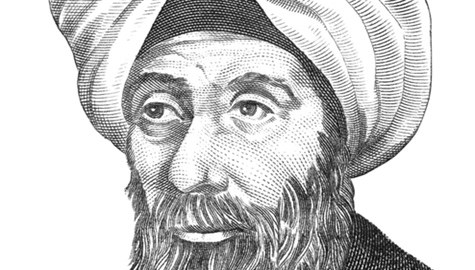

Ibn al-Haytham: The Muslim Scientist Who Birthed the Scientific Method

Editor’s Note: This article was provided by our partner, RealClearScience. The original is here.

If asked who gave birth to the modern scientific method, how might you respond? Isaac Newton, maybe? Galileo? Aristotle?

A great many students of science history would probably respond, “Roger Bacon.” An English scholar and friar, and a 13th century pioneer in the field of optics, he described, in exquisite detail, a repeating cycle of observation, hypothesis, and experimentation in his writings, as well as the need for independent verification of his work.

But dig a little deeper into the past, and you’ll unearth something that may surprise you: The origins of the scientific method hearken back to the Islamic World, not the Western one. Around 250 years before Roger Bacon expounded on the need for experimental confirmation of his findings, an Arab scientist named Ibn al-Haytham was saying the exact same thing.

Little is known about Ibn al-Haytham’s life, but historians believe he was born around the year 965, during a period marked as the Golden Age of Arabic science. His father was a civil servant, so the young Ibn al-Haytham received a strong education, which assuredly seeded his passion for science. He was also a devout Muslim, believing that an endless quest for truth about the natural world brought him closer to God. Sometime around the dawn of the 11th Century, he moved to Cairo in Egypt. It was here that he would complete his most influential work.

The prevailing wisdom at the time was that we saw what our eyes, themselves, illuminated. Supported by revered thinkers like Euclid and Ptolemy, emission theory stated that sight worked because our eyes emitted rays of light — like flashlights. But this didn’t make sense to Ibn al-Haytham. If light comes from our eyes, why, he wondered, is it painful to look at the sun? This simple realization catapulted him into researching the behavior and properties of light: optics.

In 1011, Ibn al-Haytham was placed under house arrest by a powerful caliph in Cairo. Though unwelcome, the seclusion was just what he needed to explore the nature of light. Over the next decade, Ibn al-Haytham proved that light only travels in straight lines, explained how mirrors work, and argued that light rays can bend when moving through different mediums, like water, for example.

But Ibn al-Haytham wasn’t satisfied with elucidating these theories only to himself, he wanted others to see what he had done. The years of solitary work culminated in his Book of Optics, which expounded just as much upon his methods as it did his actual ideas. Anyone who read the book would have instructions on how to repeat every single one of Ibn al-Haytham’s experiments.

“His message is, ‘Don’t take my word for it. See for yourself,'” Jim Al-Khalili, a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Surrey noted in a BBC4 Special.

“This, for me, is the moment that Science, itself is summoned into existence and becomes a discipline in its own right,” he added.

Apart from being one of the first to operate on the scientific method, Ibn al-Haytham was also a progenitor of critical thinking and skepticism.

“The duty of the man who investigates the writings of scientists, if learning the truth is his goal, is to make himself an enemy of all that he reads, and… attack it from every side,” he wrote. “He should also suspect himself as he performs his critical examination of it, so that he may avoid falling into either prejudice or leniency.”

It is the nature of the scientific enterprise to creep ahead, slowly but surely. In the same way, the scientific method that guides it was not birthed in a grand eureka moment, but slowly tinkered with and notched together over generations, until it resembled the machine of discovery that we use today. Ibn al-Haytham may very well have been the first to lay out the cogs and gears. Hundreds of years later, other great thinkers would assemble them into a finished product.

Image: Wikimedia Commons