How NASA’s ICESat-2 will track ice changes in Antarctica, Greenland

Leaving from Vandenberg Air Force base in California this coming Saturday, at 8:46 a.m. ET, the Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite-2 — or, the “ICESat-2” — is perched atop a United Launch Alliance Delta II rocket, and when it assumes its orbit, it will study ice layers at Earth’s poles, using its only payload, the Advance Topographic Laser Altimeter System (ATLAS).

The device will fire one laser split into six green beams, at 10,000 pulses each second. These pulses of light contain trillions of photons; just about a dozen will make it back to the satellite, but of those that do, it will measure how long it took for them to return to the satellite after bouncing off of ice, landscape, trees, etc.

These measurements will be taken every 28 inches (71 cm), which will return an incredible amount of data as it studies the world. For example, it will be able to track ice changes annually in the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, within 4 mm (0.16 inches).

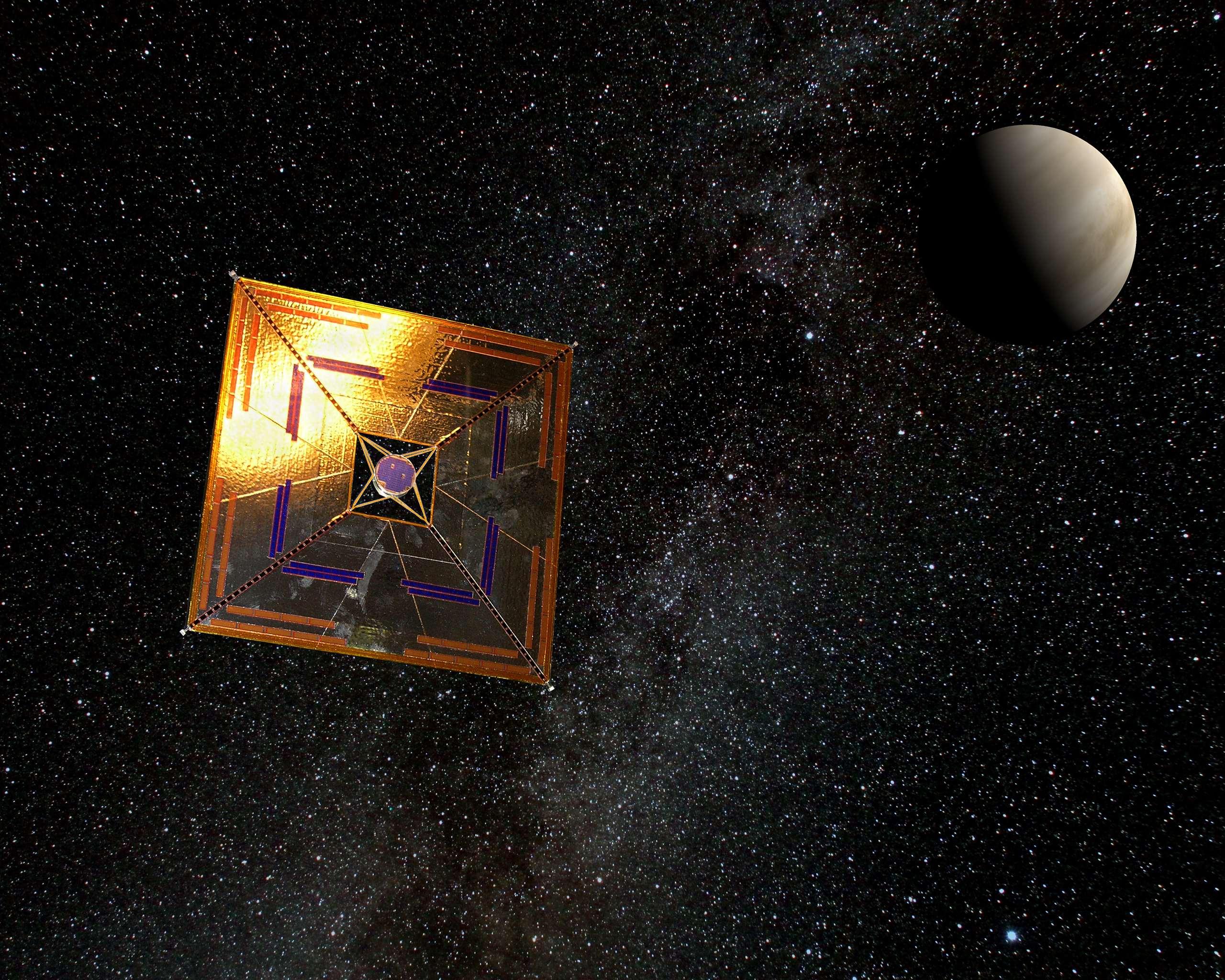

Image from NASA/Goddard video

The overarching goal here is to measure ice levels as they ebb and flow, especially at Earth’s coldest regions. That will then provide unprecedented data for those studying climate change and its impact across the world. The first iteration, ICESat-I, used a single laser, the Geoscience Laser Altimeter System, and it fired them at 40 pulses per second — 250 times slower than the new model. Data from a follow-up study using aircraft, known as IceBridge, as well as that from ICESat-I, will be used as comparisons to what ICESat-2 gathers.

Indeed, the accuracy is the thing that’s really powerful here. A press release about ICESat-2 gave a good indication of how much more precise this one is than its predeccesor:

As a comparison, if the two instruments [ICESat-I and II] took measurements over a football field, GLAS would have collected data points outside the two end zones, but ICESat-2’s ATLAS would take measurements between each yard line.

As to the technology involved, even some of the people who worked on it are shocked at its capability; Thorsten Markus, the mission’s project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, declared: “I’m a physicist, and I’m still shocked it works.”

Here are 10 quick facts about this mission that explain it quite well: