What Is Cancer?

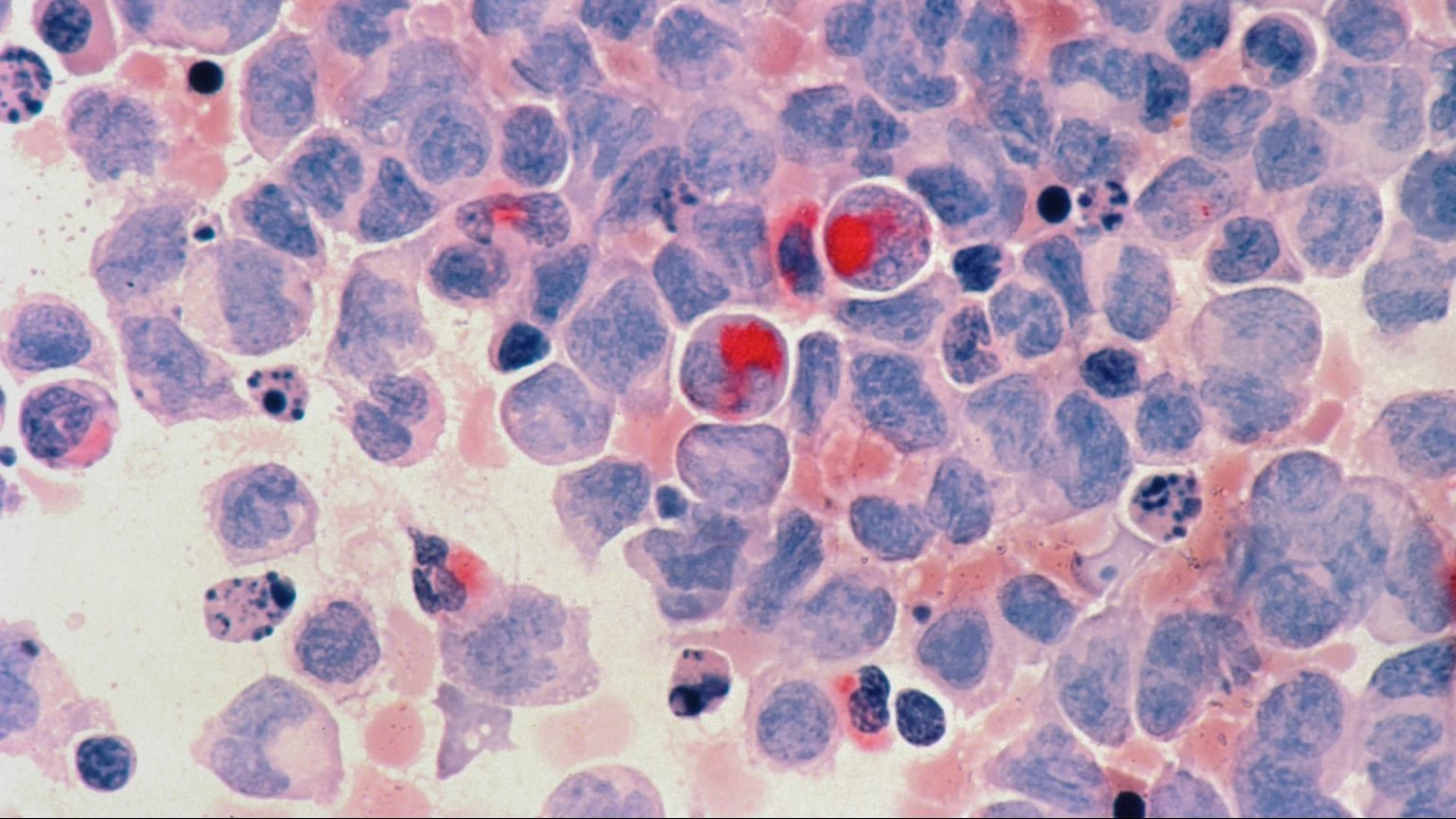

With life expectancy over 30 years greater than it was 100 years ago, cancer has become an inescapable part of our modern lives. One in three Americans will develop some form of cancer during their lifetimes, and roughly 560,000 Americans die each year from cancer. During Big Think’s panel discussion on cutting edge cancer research, the third and final installment of our Pfizer-sponsored Breakthroughs series, Nobel Prize-winning scientist Harold Varmus describes cancer as a derangement of normal cell growth: “Cells grow too much and they grow in antisocial ways,” he explains. “They cross normal tissue boundaries. They invade. They can grow in other places where they shouldn’t be growing. They often fail to differentiate the way normal cells will.”

But unlike many other disease, cancer is not a foreign invader—it is actually a part of you, gone wrong. “The cancer cell is your own body, your own cells, just misbehaving,” says Nobel-prize winner Paul Davies in his Big Think interview.

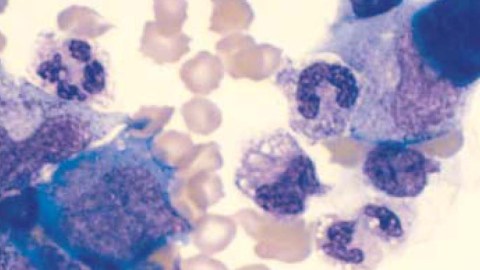

Cancer can arise in virtually any human tissue, and these different cancers—lung, prostate, breast, for example—are different in their genetic makeup and behavior. It isn’t a single disease, but hundreds. Leukemia, for example, “has broken out from a single leukemia to dozens of leukemias that are defined differentially based on what chromosomal change can be seen in a microscope,” says Lewis Cantley, a professor of cell biology at Harvard. “We’re now taking it to an even deeper level where we can go in and sequence the entire genome of the cancer and these mutations keep giving us more and more subtypes.”

On the one hand, this extreme heterogeneity among cancers is daunting for scientists, and it explains why individual drugs rarely cure all incidences of each type of cancer. At the same time, our new ability to sequence cancer genomes promises more targeted and individualized treatments that could prove less toxic and ultimately more successful. But trying to create drugs for each of the hundreds, if not thousands, of cancer variations would be extremely difficult and expensive. So while we seek to become more targeted in our approach to treatment, we also must take a macro perspective, looking for commonalities across different subtypes, says Varmus: “In many cases you can say, yes, there are hundreds of different cancer types that look the same; they look different genetically, but frequently there are commonalities that can be points of attack, mutations that act as drivers of the cancer behavior.”

More Resources:

—The New York Times: Cancer Health Guide

—Big Think Editors: “A Universal Cure for Cancer?“

—Big Think interview with Clifford Hudis, Chief of the Breast Cancer Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

The views expressed here are solely those of the participants, and do not represent the views of Big Think or its sponsors.