Scientists plan to spray the sky with light-reflecting particles to dim the sun

Image: Shutterstock/Big Think

- Scientists hope to launch the world’s first solar geoengineering project next year.

- The project involves spraying calcium carbonate into the stratosphere.

- The team hopes to get people thinking more seriously about bioengineering.

If all the pieces can be put together by then, a trio of researchers from Harvard hope to begin the testing phase of their plan to reduce the amount of sunshine the Earth receives as a means of cooling down the planet as it heats up from climate change. If they manage to spray some calcium carbonate particles into the stratosphere — essentially airborne TUMS®, minus the berry flavor — theirs would be the first solar geoengineering project off the drawing board and into the skies.

To say the plan, detailed in Nature, is controversial is putting it mildly — even the team itself, David Keith, Zhen Dai, and Frank Keutsch — has doubts about the whole idea. Environmentalists are concerned that geoengineering climate fixes are a distraction from better, if difficult, solutions involving more intelligent, sustainable consumption of carbon-producing substances. They’re also concerned that manipulating Earth’s complicated natural balance is rife with unforeseeable consequences, just another example of placing too much faith in engineering, which, after all, got us into this mess in the first place.

(Nature)

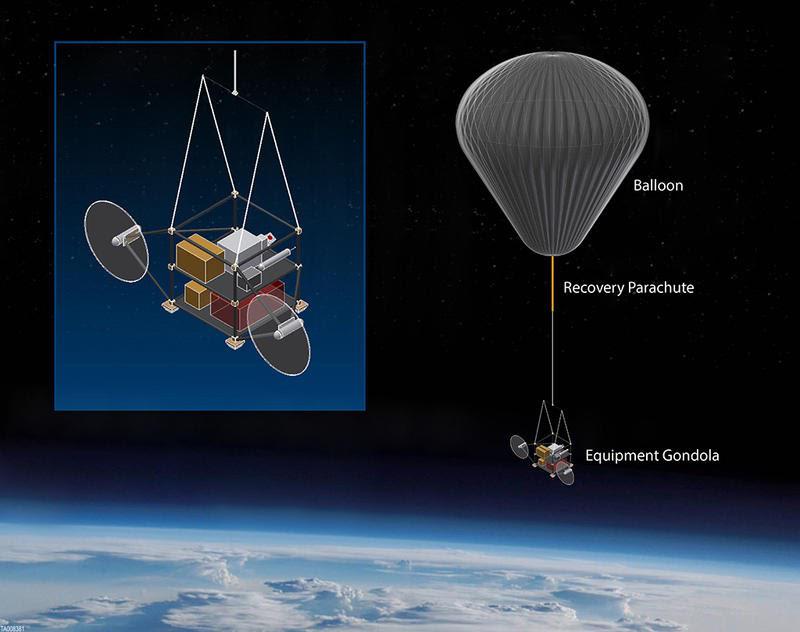

The SCoPEx experiments

The name of the Harvard team’s project is SCoPEx , for “Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment.” Their plan is to launch two steerable balloons over the U.S. Southwest, each of which would spray about 100 grams of calcium carbonate, about the same amount packed into a single antacid tablet, into the stratosphere. The balloon would then reverse course to observe what happens to the dispersed 0.5 micrometer particles — the researchers think that’s about the right size for both dispersal and reflecting sunlight.

As simple as this sounds, it’s not. First off, the balloons will have to be able to turn around in order to observe what they’ve left behind. Second, they need some form of detection that can, first, locate the calcium carbonate plume and second, measure the size and number of particles. A team from NOOA’s Boulder, CO, office led by David Fahey, is providing the equipment for performing these measurements, though Fahey warns, “It’s going to be a hard experiment, and it may not work.” Third, hopefully, the balloons will be able to recapture some particles for a return to the ground. The balloons may also have onboard a laser device for tracking the plume at a distance and other sensitive gear for collecting data on moisture and ozone levels.

The idea of spraying particles into the upper atmosphere is not new, though this would be the first actual attempt to do it. Scientists know the idea can work, since it occurs naturally in the wake of volcanic eruptions, such as the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines in 1991. That event sent aloft an estimated 20 million tonnes of sulfur dioxide that cooled the planet by 0.5° for about 18 months, bringing it back to pre-steam-engine temperature levels.

The switch to calcium carbonate for SCoPEx has to do with sulfur’s damaging effect on the ozone layer. The SCoPEx experiment is, of course, limited in scope, and Dai says, “I’m studying a chemical substance. It’s not like it’s a nuclear bomb.” Still, there’s concern about monkeying with the atmosphere and sunlight. Principle investigator Keutsch notes, “There are all of these downstream effects that we don’t fully understand.” Solar engineering has the potential to disrupt natural precipitation patterns, leading to both deluges and droughts, and its effect on agriculture isn’t clear: While plants suffer less heat stress in a slightly darker, cooler environment, they also wouldn’t get as much sun. Keith is cautiously optimistic, though, saying, “Despite all of the concerns, we can’t find any areas that would be definitely worse off. If solar geoengineering is as good as what is shown in these models, it would be crazy not to take it seriously.”

As far as the choice of calcium carbonate goes, it’s not a chemical that exists at all naturally in the stratosphere, where SCoPex plans on spraying it. “We actually don’t know what it would do, because it doesn’t exist in the stratosphere,” says Keutsch, “That sets up a red flag.” When he first learned about the already in-progress SCoPex research, he says, he thought it was “totally insane.”

([irin-k]/Shutterstock/Big Think)

One unmistakable benefit of the SCoPex plan

Given SCoPex’s status as the first solar geoengineering project, it’s under intense scrutiny, and that’s just fine with the researchers. It’s as much about starting a conversation as anything else. As Jim Thomas of ETC Group, an environmental advocacy organization opposing geoengineering, puts it, “This is as much an experiment in changing social norms and crossing a line as it is a science experiment.”

Many believe that as climate change becomes more dire, there’s a greater chance that geoengineering will become seen as more attractive, at least as a supplement to conservation efforts, even to those who currently oppose it. There’s currently no robust evaluation structure in place to assess the worthiness of geoengineering proposals, and some are concerned about this. Janos Pasztor, of the Carnegie Climate Geoengineering Governance Initiative, has been trying to engage leaders in the conversation. “Governments need to engage in this discussion and to understand these issues,” he says. “They need to understand the risks — not just the risks of doing it, but also the risks of not understanding and not knowing.”

The Harvard researchers themselves are deliberately moving ahead slowly, working to put in place sensible oversight of SCoPex, setting up an external advisory committee to assess their plan and report to the vice-provost for research at Harvard. It may well be that establishing such a model framework will be more important in the long run than the results of the SCoPex experiment itself.