Special Effects: Police Brutality and the Media

After 7-year-old Aiyana Jones was shot and killed by police during a raid filmed for a cable show, experts are asking whether the officers responded to the cameras with violence.

This past Sunday, May 16, police raided Jones’s Detroit home, searching for a suspect of a murder that had occurred earlier that weekend. The police threw a stun grenade through the house’s front window, and that’s where the stories diverge. Police allege that when they entered the home, an officer struggled with Aiyana’s grandmother, at which point the officer’s gun discharged, hitting Aiyana. The family’s attorney claims otherwise, saying that the grenade lobbed through the window landed on Aiyana, and that an officer fired into the house almost immediately after—that is, before entering the house. At a press conference on Tuesday, Aiyana’s grandmother denied being involved in any struggle with the officers. We don’t yet know whether the shot was fired before or after the officers entered the house, but the incident was filmed by a crew from A&E’s “The First 48” crime reality show, which the family’s attorney claims proves his version of events.

As RaceWire’s Juell Stewart tells us, it’s happening again: “A young person of color gets killed by the police, the community rallies around the victim’s family, and everybody wonders what can be done to prevent it from happening again.” Of course, the police don’t need to have a camera around to use excessive force, but Aiyana’s family is putting forth the possibility that “the police operation was flawed and heavily influenced by camera crews who were filming the raid.” The police had a warrant which would have allowed them to search the home without the residents’ consent, but Aiyana’s family and others “have questioned what effect the cameras may have had on the tactics used during raid on the home, which had toys strewn about the front lawn.”

My first impulse is to think that having cameras around would promote more accountable police work. Having a record of police actions would theoretically make police think harder about using force. Take the beating of Rodney King: the video evidence gave the outrage over the violence firm ground to stand on. More recently, this past month Seattle police officers searching for robbery suspects stopped a young Latino man named Martin Monetti and forced him to lie on the ground. A freelance journalist caught the incident on tape, and the video shows officers kicking Monetti in the face, stomping on his leg, and yelling “I’m going to beat the fucking Mexican piss out of you homey. You feel me?” Because of the video evidence, the police department has launched a criminal investigation into the violence. Sometimes even the police’s own cameras catch excessive uses of force.

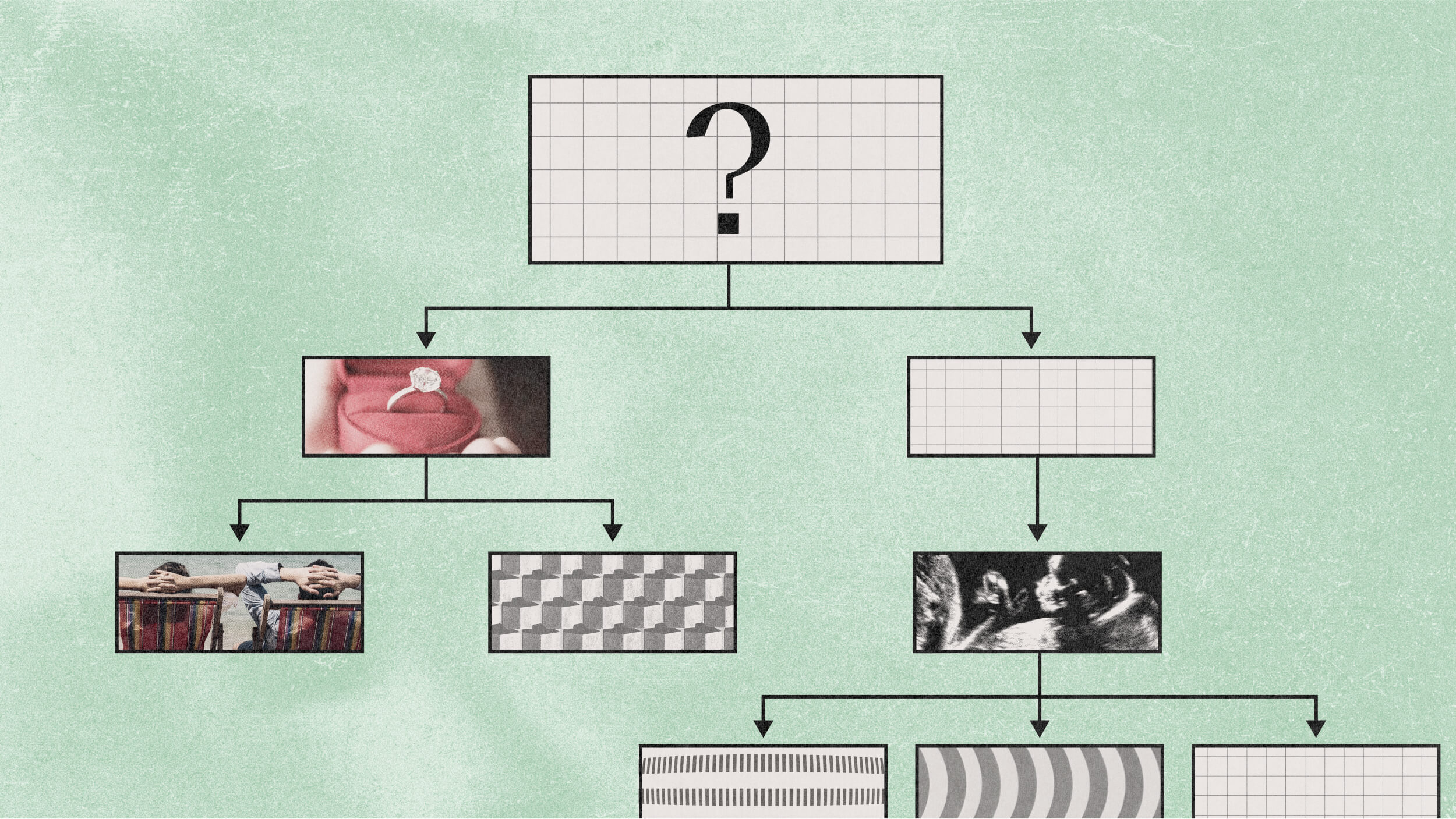

But the officers involved in Aiyana’s death were being filmed for television, not for evidence, and that may be the important difference. The officers used flash grenades when they knew children were present, something Detroit police have rarely—if ever—done in the past. The cameras that ride along as police make their rounds get the background and context for arrests from the police rather than from the arrested, and the police admit that shows such as “The First 48” work well to recruit new officers. But when police work is used for entertainment, arrests have to grip viewers and boost ratings, but maybe good, real world police work shouldn’t involve any special effects at all.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons, user Nicky Dracoulis.