What AI’s sensory void tells us about thinking on “the road to meaning”

- Current text-based LLMs lack sensory experiences and iconic representations, potentially limiting their ability to ground language in real-world meaning.

- Meaning can be acquired through word associations and sensory experiences, but while humans benefit from both, LLMs are limited to the linguistic route.

- In his book These Strange New Minds, Summerfield hypothesizes that the development of AIs that can process images and videos may bring AI cognition closer to human-like understanding.

It’s definitely safe to assume that current text-based LLMs, which have never seen the real world and thus have no iconic representations with which to ground their learning, are aphantasic — they never think with pictures. But does this mean that they are incapable of thinking at all, or that their words are entirely devoid of meaning?

To address this question, let’s consider the story of a human who grew up with severely limited opportunities to sense the physical world. Helen Keller was one of the most remarkable figures of the twentieth century. Born into a venerable Alabama family, at just nineteen months old she suffered a bout of meningitis and tragically lost both her sight and hearing. She spent the next few years struggling to make sense of the world through her residual senses, for example recognizing family members by the vibration of their footsteps. At the age of six, her mother hired a local blind woman to try to teach her to communicate by drawing letters on her hand. In her autobiography, Keller emotionally recounts the Damascene moment in which she realized that the motions W– A– T– E– R on her palm symbolized the wonderful cool thing flowing over her hand. As she ecstatically put it: “The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!”

Keller’s story gives us a fascinating insight into what it is like for a person to grow up in a sensory environment that is stripped of visual and auditory reference. At first glance, her tale seems to vindicate the idea that words take on meaning only when they are linked to physical experiences. She eventually understood the word water when she realized that it referred to an experience in the physical world – the cool sensation of liquid running over her hand. It’s as if Keller is recounting the exact moment when she is able for the first time to match symbols to real-world entities, allowing their meaning to come flooding in. By contrast, LLMs (which unfortunately do not have hands, and cannot feel the coolness of water on their fingers) remain imprisoned.

However, there is a catch. Defining words as meaningful only when they refer to concrete objects or events (like a real monkey riding a real bicycle) would radically denude vast swathes of language of their meaning. We understand lots of words that do not refer to physical things, and cannot be seen, heard, or otherwise directly experienced: words like square root, nonsense, and gamma radiation. We can all reason perfectly well about things that don’t exist (and thus have no referent) like a peach the size of a planet or a despotic whale that rules the Indian Ocean. Helen Keller herself grasped the meaning of countless concrete concepts that she could not see or hear, such as cloud, birdsong, and red. So words do not become meaningful exclusively because they refer to things that can be seen, heard, touched, tasted, or smelled. They also obtain meaning through the way they relate to other words. In fact, the claim that “meaning” and “understanding” arise only when words are linked to physical sensations unjustly implies that speech produced by people with diminished sensory experiences is somehow less meaningful, or that they are themselves less able to “understand” the words that they speak. These claims are clearly both false. Helen Keller, who never recovered her sight or hearing but went on to become a revered scholar, writer, political activist, and disability rights campaigner, owed much of her wisdom to the meaning that language conveys through its intrinsic patterns of association — the way words relate to other words.

So meaning can be acquired via two different routes. There is the high road of linguistic data, in which we learn that spider goes with web. Then there is the low road of perceptual data, in which we catch sight of an eight-legged insect at the centre of a geometric lattice, glinting in the morning dew. Most people have the luxury of traveling down both routes, and so can learn to connect words with words, objects with objects, words with objects, and objects with words.

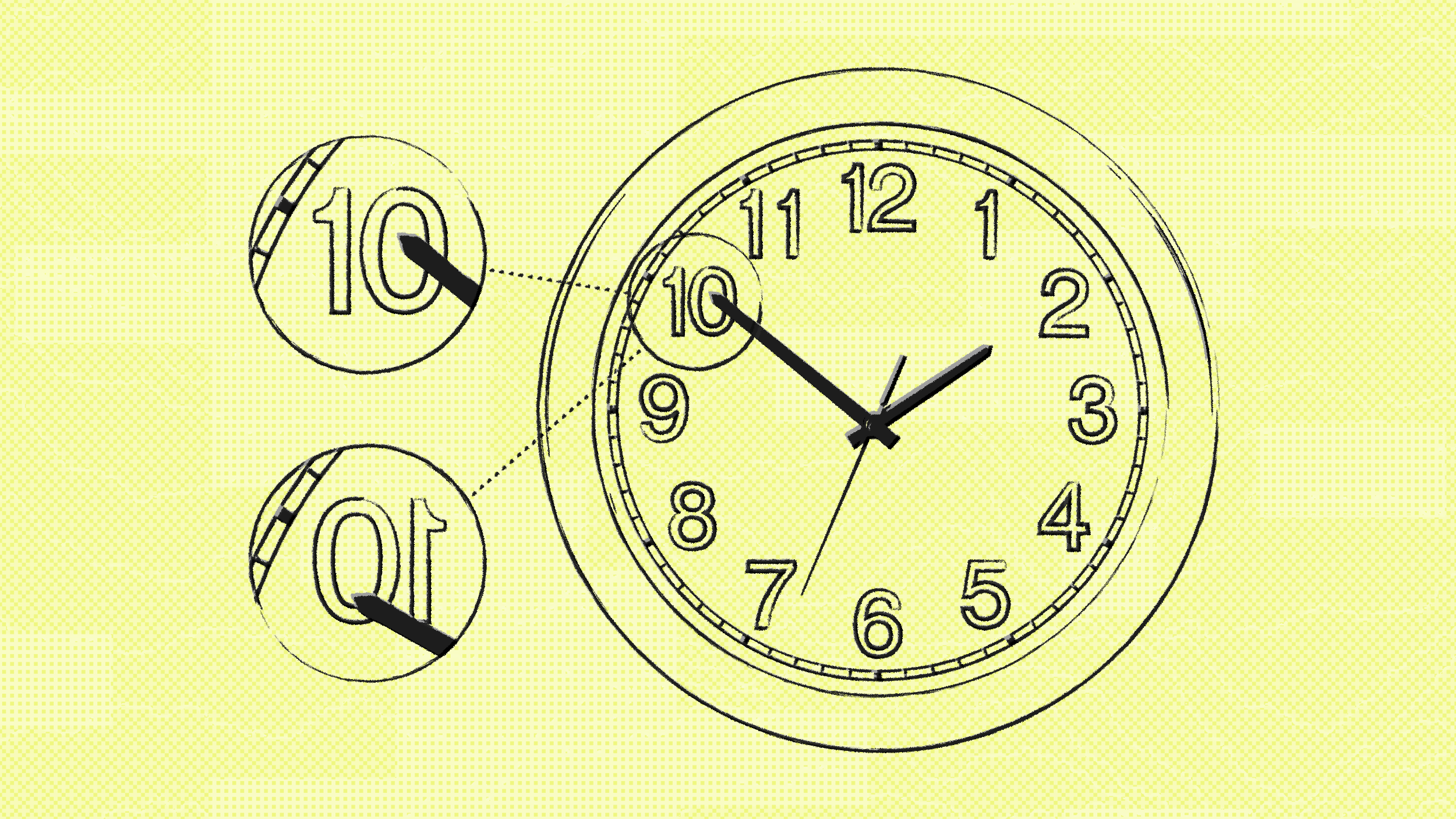

LLMs that are trained exclusively as chatbots, by contrast, can only travel on the high road — they can only use linguistic data to learn about the world. This means that any thinking or reasoning that they might do will inevitably be very different from our own. We can use mental representations formed by our first-hand experience of objects or space or music to think about the world, rather than having to rely solely on propositions in natural language. This is why, for humans, thinking and talking are not inextricably linked. As one recent paper puts it, our “formal” linguistic competence (being able to construct valid sentences) does not bound our “functional” linguistic competence (being able to reason formally or display common sense). Clear evidence for this dissociation comes from patients who have suffered damage to the parts of their brain involved in producing language. If you are unlucky enough to have a stroke that affects the left side of your brain, you might end up with a deficit called aphasia. Aphasic patients typically have difficulties with articulation, inability to find the right words (anomia), or problems forming sentences (agrammatism). However, human deficits of sentence generation don’t necessarily go hand in hand with thinking difficulties, because aphasics often have remarkably intact reasoning or creative powers.

As LLMs evolve beyond chatbots, their opportunities to learn about relational patterns in the physical world — from photographs and videos — will dramatically improve, and as they do so, their way of thinking will move a step closer to our own.

Christopher Summerfield

Most current publicly available LLMs are primarily chatbots — they take text as input and produce text as output (although advanced models, such as GPT- 4 and Gemini, can now produce images as well as words — and text-to-video models will soon be widely available). They have been trained on natural language, as well as some formal languages, and lots of examples of computer code. Their capacity for logic, maths, and syntax is thus wholly grounded in their internal representations of these symbolic systems, such as Korean or C++.

Humans, by contrast, enjoy real-world experiences which are not limited to words. This means that we can use other sorts of mental representations for thinking, such as the pleasing pattern of notes that hit the ear when listening to a string quartet, the geometric projection of an algebraic expression or the strategic spatial arrangement of pieces on a chessboard when plotting a checkmate. This is why, when the language system is damaged, our ability to reason is partly spared — we can fall back on these alternative substrates for thought. This is thus another way in which LLM cognition is strikingly different from human cognition.

The next generation of multimodal LLMs is arriving — those that receive images and videos as well as language as input. As LLMs evolve beyond chatbots, their opportunities to learn about relational patterns in the physical world — from photographs and videos — will dramatically improve, and as they do so, their way of thinking will move a step closer to our own.