MIT invents $4 solar desalination device

- Water covers more than two-thirds of Earth’s surface, but 97% of it is undrinkable saltwater.

- Engineers have created countless solar desalination devices, but for the devices to make a difference in the places that need them the most, they need to be not only cheap and efficient, but also durable and long-lasting.

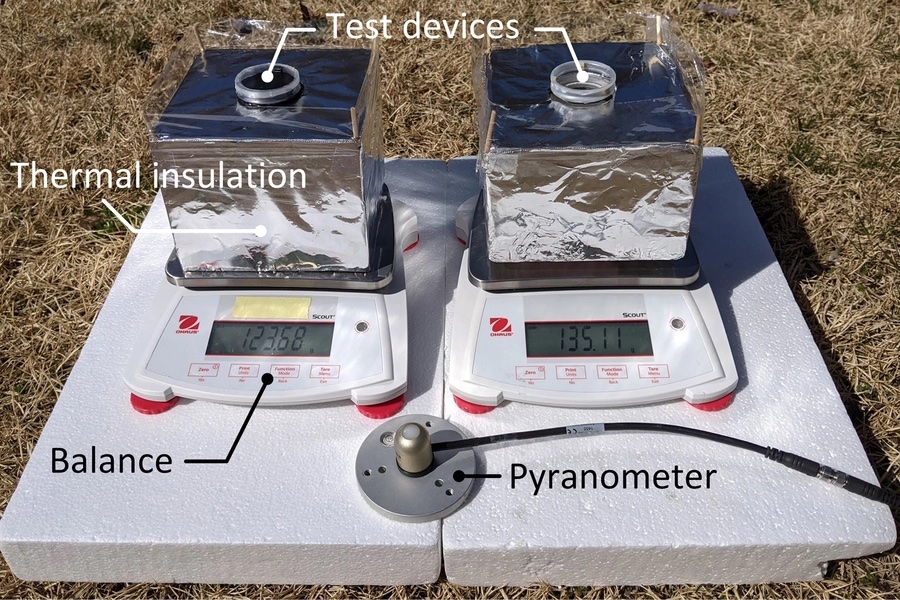

- A new, cheap solar desalination device uses gravity-driven convection to purify water.

Researchers from MIT and China have developed a solar desalination device that could provide a family of four with all the drinking water it needs — and it can be made from just $4 worth of materials.

Solar desalination: Water covers more than two-thirds of Earth’s surface, but 97% of it is saltwater. The salt concentration in that water is far too high for our bodies to process — if you drank too much of it, you’d actually become dehydrated and die.

What we need is freshwater, meaning a salt concentration of less than 1%, and since this water isn’t as abundant, humans have come up with lots of ways to remove enough salt from saltwater to make it drinkable.

“I think a real opportunity is the developing world.”

EVELYN WANG

One of those is solar desalination.

While the specifics vary, the basic idea is that the sun’s heat is applied to saltwater. The water evaporates, leaving behind the salt, and the water vapor is then collected and condensed, leaving you with liquid freshwater.

Getting salty: Engineers have created countless solar desalination devices, but for the devices to make a difference in the places that need them the most, they need to be not only cheap and efficient, but also durable and long-lasting.

“We see these very attractive performance numbers, but they’re often limited because of longevity.”

EVELYN WANG

The problem is that salt tends to build up in these devices, particularly on the wick used to pull water through the device. Those wicks are difficult to clean, and over time, the salt accumulation means they have to be replaced.

“The challenge has been the salt fouling issue, that people haven’t really addressed,” researcher Evelyn Wang told MIT News. “So, we see these very attractive performance numbers, but they’re often limited because of longevity. Over time, things will foul.”

The idea: Researchers from MIT and China’s Shanghai Jiao Tong University have now created a wick-free solar desalination device that uses gravity-driven convection to move the water.

Natural convection is a type of movement that occurs when a liquid isn’t one uniform density. In that situation, the less dense liquid will rise, while the denser liquid falls. (The same is true of gases — because hot air is less dense than cold air, it rises while cold air falls.)

How it works: The new solar desalination device consists of several layers. Salt water is added to the top layer. Black paint draws the sun’s heat to that layer, causing the desired creation of water vapor for collection.

Any water left behind in that layer is then extra salty and, therefore, extra dense.

The very bottom layer of the device contains more saltwater. The layers between it and the top are designed to keep heat in the top layer, while allowing the super-dense saltwater to move downward to mix with the normal density saltwater under the power of natural convection.

Looking ahead: The device worked for a week straight with no signs of salt accumulation, but we still don’t know exactly how long it could operate.

But the best news is that it would cost just $4 to build a solar desalination device large enough to meet the drinking water needs of a family of four, according to the MIT team. If it does prove durable, it could be a relatively cheap way to get freshwater to people in need of it.

“I think a real opportunity is the developing world,” Wang said. “I think that is where there’s [the] most probable impact near-term, because of the simplicity of the design.”

This article was provided by our sister site, Freethink.