Harvard negotiator explains how to argue

- Arguments are a necessary part of life, but they don’t necessarily have to be fraught.

- Psychologist Dan Shapiro has identified three barriers to productive arguments: an us-versus-them identity, not showing appreciation, and a lack of affiliation.

- Breaking through these barriers requires us to be better listeners and to recategorize our sense of “us.”

I hate arguments. I hate the way it feels when my blood pressure rises and the cortisol kicks in. I hate the frustration that comes from talking past one another or reaching an impasse on an important issue. I especially hate the awkward apologies I have to dole out the morning after — because I definitely shouldn’t have said that, and yes, it was a cheap shot.

It doesn’t seem like I’m alone here. While some people will inflame crossfire for the thrill of it, such people are a fringe minority. Most people, I believe, want arguments to be constructive. They worry that our politics have become too polarized, and that social media is the culture wars’ most toxic battleground. And in their personal lives, they fret when promising relationships struggle to bridge entrenched disagreements.

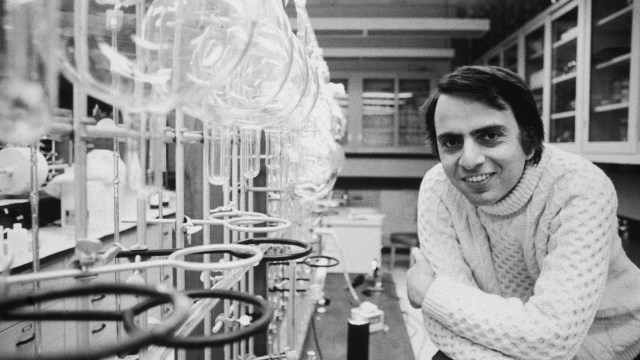

Even Dan Shapiro, an expert on negotiation and conflict resolution at Harvard University, finds conflict uncomfortable. But as he mentioned in an interview, arguments are a universal human experience. We can’t avoid it, and we ignore it to our detriment. No matter how much we may dislike it, we need to be able to engage in life’s arguments, whether they resolve in our favor or not. As such, Shapiro notes, the problem isn’t that we have arguments. “The problem is with the how.”

In his research and experience, Shapiro has identified three barriers we need to overcome to have better, more productive arguments.

Barrier 1: An us-versus-them identity

The purpose of an argument changes the moment your identity becomes entangled in the conflict. At that point, you’re no longer trying to resolve a disagreement or hashing out competing ideas. You’re fighting for your sense of self. It’s now you (as an individual) or us (as a tribe) versus them. Once you’re in that self-defense mode, your emotions become more powerful, and your desire to find common ground gives way to a need to win.

Unfortunately, it’s frightfully easy for arguments to devolve into an us-versus-them challenge. In fact, while we naturally cooperate with members of our in-group, we are also naturally out-group phobic. Research shows that when people strongly identify with an ideology, they can dehumanize the out-group to the point of underestimating their ability to feel basic human sensations, such as thirst and cold. They are also more likely to ascribe the other side’s motivations as nefarious and hateful.

This is more than poor reasoning on our part. The us-vs-them mentality has a neurological underpinning in the hormone oxytocin.

Oxytocin is typically valorized as a prosocial hormone. It is an important contributor to behaviors such as building trust, increasing cooperation, and reducing social wariness. It makes us more emotionally expressive and improves our emotional intelligence. It even helps mothers bond with their babies and couples with each other. But research has also shown that oxytocin isn’t just a hippy hormone. The same hormone that triggers in-group cohesion may also strengthen out-group competition. This dual role of making both love and war is referred to as the “oxytocin paradox.”

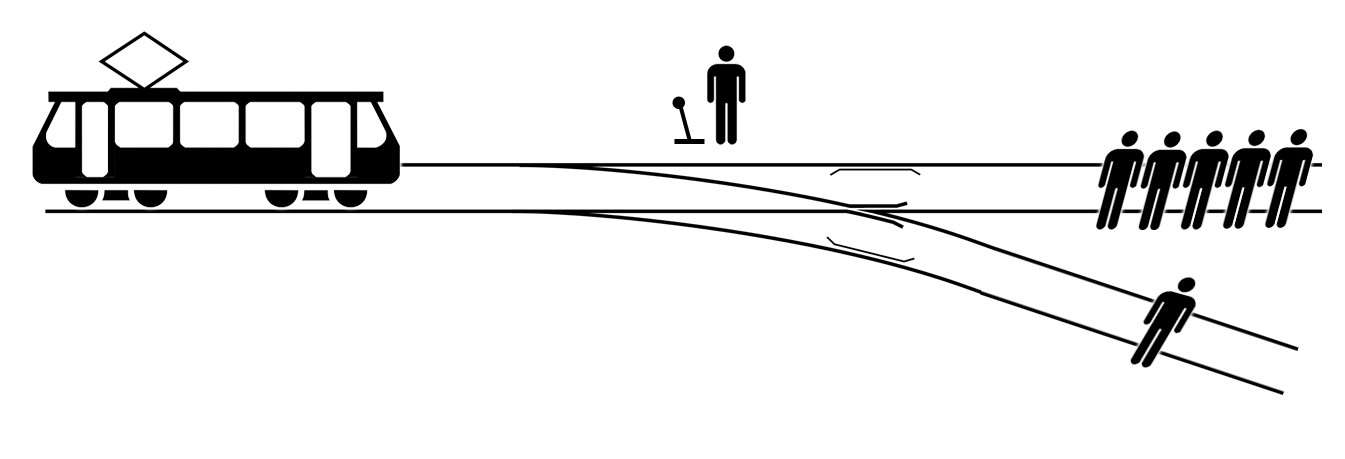

In a Big Think interview, neurologist Robert Sapolsky shared an experiment from the Netherlands that gave participants a nasal spray of either oxytocin or a placebo before tasking them with a moral dilemma. After their spritz, participants were asked to imagine a runaway trolley barreling toward five people; however, they could pull a switch that would divert the trolley. By diverting the trolley, they would save the five people but kill another person in the process. In a twist to the classic trolley problem, this lone victim was given a name. That name was either a typical Dutch name (such as Dirk) or a typical Arab name (such as Ahmed).

Participants who took the placebo sacrificed both Dirk and Ahmed at roughly similar rates. But those who received a hit of oxytocin were far more willing to sacrifice poor Ahmed over Dirk.

“When you look at some of the most appalling realms of our behavior, much of it has to do with the fact that social organisms are hardwired to make a basic dichotomy about the social world — which are those organisms who count as us’s and those who count as them’s,” Sapolsky said.

How do we overcome this barrier? Unfortunately, because this barrier occurs at the level of hormones and the unconscious mind, we can never have complete control. However, we can exercise some control over how it manifests in our outward behavior. The first step is simply to be aware of identity’s power to sway your emotions and rationale. With that self-perspective, you can then begin to reason through these emotions. Learn to recognize your identity triggers and when your defenses become heightened. Ask yourself why and try to devise ways to lower those defenses.

As Shapiro pointed out: “You need to know who you are and what you stand for. What are the values and beliefs that are driving me to fight for this stance on this issue? The more you understand who you are, the more you can try to get your purpose met and stay balanced, even when the other threatens those core values and beliefs.”

Of course, no one is perfect. We’ll all lose our balance from time to time, so it may help to practice those morning-after apologies, too.

There is nothing more in the world that we like than to feel appreciated. Recognize your power to appreciate them.

Dan Shapiro

Barrier 2: Not showing appreciation

Once we see how identity plays into our emotional defenses, we can then work to lower those defenses in ourselves and others. One way to do that and build a better connection is through appreciation. Acts of appreciation show that you don’t view the argument as a knockdown ideological brawl; the other person’s loss isn’t your gain. Rather, you view the argument as an opportunity for potential resolution, and even if that can’t be reached, mutual growth and new understanding.

An approach Shapiro recommends is to simply listen at the start of the conversation. Consider the value behind the other person’s perspective, their rationale, and why they hold it. Even if you don’t ultimately agree, you’ll likely find something that you appreciate about the other person — whether that’s their values, passion, knowledge of the subject, or a nuanced take you hadn’t considered.

“Once you truly understand and see the value in their perspective, let them know I hear where you’re coming from,” Shapiro said. “There is nothing more in the world that we like than to feel appreciated. Recognize your power to appreciate them.”

A more formalized approach to overcome this barrier is known as Rapoport’s rules. First devised by mathematical psychologist Anatol Rapoport and later synthesized by Daniel Dennett, these rules offer a step-by-step guide to bringing appreciation into a debate or argument.

After listening to the other side’s rationale, follow these steps:

- Explain the other person’s position clearly to demonstrate that you listened and respect the other person’s position.

- Mention anything you’ve learned to show the other person that they are worthy of learning from and that you appreciate the opportunity.

- List the points on which you agree as a way of lowering those self-defenses.

- Only now, offer a critique or refutation.

By engaging in either Rapoport’s rules or Shapiro’s recommendation, you demonstrate not only appreciation but also build trust with the other person. And you can utilize that trust to propel you past the final barrier.

Barrier 3: Ignoring your affiliation

As we’ve seen, when we think of someone as a part of our in-group, we are more cooperative and more willing to think of them as partners rather than ideological obstacles. When we view them as a member of the out-group, we see them as an adversary or a lamb for the trolley slaughter.

But according to Sapolsky, we are easily manipulated when it comes to assigning who belongs in or out of our group. Believe it or not, that’s the good news*. We can connect with other people — associate them as part of our tribe — based on seemingly inconsequential traits. It can be as simple as a shared hobby, a favorite sports team, or whether their second cousin’s former roommate is a graduate of our alma mater. Even the most tenuous affiliation can open the doors to “us-ness” and reduce self-defenses by easing tribal loyalties.

“Turn that other person from an adversary into a partner, so it’s no longer me versus you, but the two of us facing the same shared problem,” Shapiro said.

The affiliation need not be inconsequential either. Consider the immigration debate in American politics. In many ways, these arguments are intractable. Economic realities are complex, humanist aspirations can be daunting to achieve, and identities in such issues are deeply rooted.

However, polling data suggest that Republicans and Democrats actually agree on a lot. A majority of both say that border security, allowing undocumented children to stay, and helping civilian refugees escape violence are important goals. The difference is in degree and intensity, which shifts the top priorities for each side. Even so, it’s one thing to say you have a different priority than to say both sides share no affiliation on the challenge at all.

As such, overcoming this third barrier can be as simple as reminding those involved about what they have in common — whether that’s a shared value, priority, or goal. Rapoport’s rules do this by listing the points of agreement in advance of contentious issues. Shapiro also recommends asking the other person to imagine solutions that incorporate as many shared values and priorities as possible. In the case of immigration, that imagined solution would be one that improves border security and the legal visa system while disengaging from shibboleths such as “immigrants steal jobs.” The result may not be anybody’s idealized fix for the problem, but it can still help build a sense of connection and shared problem-solving.

“Now, if you put these three things into practice, it can transform your relationships. Imagine what would happen if we started a revolution, but a positive revolution of greater understanding, greater appreciation, greater affiliation, how we could transform politics, how we could transform our country and, ultimately, our world. I believe it’s possible, but it starts with each one of us,” Shapiro said.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

*Note: Of course, in this case, the good news is also the bad news. Sapolsky also points out that manipulating in-group perception is the go-to playbook of ideologues and demagogues. By pointing to differences and ignoring important similarities, such bad players make the in-group feel more exclusive than it actually is.