An enduring “fact” about the 1918 flu might be wrong

- The 1918 flu is often believed to have killed healthy young adults as frequently as the very young and old, based mostly on anecdotal accounts.

- However, researchers analyzing skeletons from the pandemic found that frail individuals were more likely to die than healthy ones.

- This challenges the perception that young adults were disproportionately affected.

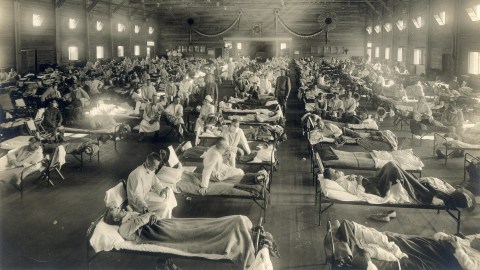

The 1918 flu pandemic (which lasted from February 1918 to April 1920) infected an estimated 500 million people and killed 25 to 50 million, representing between 1.3% and 3% of the global population. These numbers make the COVID-19 pandemic seem benign by comparison: As of July 2023, COVID-19 had killed an estimated 6.95 million people, representing roughly 0.09% of the global population.

A frightening and oft-repeated fact about the 1918 flu is that it killed healthy young adults in their twenties just as often as it did the very young and the very old. This is quite out of the ordinary for infectious diseases. As William Paul Glezen, a distinguished emeritus professor in the Baylor College of Medicine’s Department of Molecular Virology & Microbiology, wrote, “[it] was not just the weak and infirm who were taken away but the flower and strength of the land.”

Looking back at the 1918 flu

Researchers have proposed an explanation for the 1918 flu’s brutal impact on the young and healthy. They suggest that the generation of young adults during the 1918 flu was exposed to a very different H3N8 flu virus as infants between 1889 and 1892, which shaped their immune systems in a way that made them more vulnerable to the H1N1 1918 flu.

But when Amanda Wissler and Sharon N. DeWitte, anthropologists respectively based out of McMaster University and the University of Colorado, searched for hard evidence to back the notion that the 1918 flu was disproportionately deadly to young adults, they came up mostly empty. The historical literature is filled with anecdotal accounts, but hard data was difficult to find. A 2013 paper claimed to find evidence of increased young adult mortality from the 1918 flu in historical registers from various cities across the U.S. and Canada, but methodological limitations make the findings difficult to accept.

So Wissler and DeWitte sought to plug the evidence gap in the scientific literature by examining the skeletons of people who died during the 1918 flu pandemic and comparing them with skeletons of people who died prior to the pandemic. For this, the duo turned to the Hamann-Todd Human Osteological Collection of 3,000 skeletons housed in the basement at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The museum graciously allowed the researchers access to 81 skeletons of people who died during the pandemic and 288 who died before the pandemic but after 1910.

Specifically, Wissler and DeWitte examined the bones for specific lesions on the tibia (shinbone), which form due to injury or systemic disease and inflammation. Individuals with these lesions were likely frail and infirm before their death. If skeletons without lesions (healthy people) were just as common among the dead as skeletons with lesions (frail people), that would support the notion that the 1918 flu was just as deadly to healthy and young adults as frail and old adults.

However, this was not what the researchers found. Bunking the conventional narrative about the 1918 flu, Wissler and DeWitte’s analysis indicated that frail people were 2.7 times more likely to die than healthy people — just as one would expect from a typical outbreak of infectious disease.

The researchers’ sample group was small and limited to one city, so it’s very possible that their findings might be out of step with what happened nationally or globally. Moreover, the cause of death for the individuals was not documented. All of the skeletons were actually from persons whose bodies were unclaimed.

Explaining historical accounts

But let’s suppose Wissler and DeWitte are correct and the 1918 flu really wasn’t an anomaly in terms of who died. What could explain all of the historical accounts that healthy people were equally likely to be stricken?

“The risk of death for everyone increased during the pandemic indicating that more healthy people died during the pandemic than would have in normal, nonpandemic times,” the researchers explained. “It is possible the perception that healthy adults were equally likely to die of the flu reflects the fact that young adults were certainly at greater risk in the 1918 flu. Unusually high numbers of deaths among young adults would have been memorable and disruptive to both labor force and family life.”

The 1918 flu also struck at a time when millions of young, American men were massed together in army camps and barracks during and after World War I. In these crowded conditions, they were likely sickened at higher rates than older individuals. Even if a very small portion of them died relative to other individuals who became infected, their deaths would still have been numerous and memorable.