Ancient fashion: 3,200-year-old pants on Chinese mummy are like modern-day jeans

- Archaeologists took a closer look at the world’s oldest pair of pants, recovered from China’s Tarim Basin.

- With help from fashion designers, they determined that the trousers employed various weaving techniques to make the wearer comfortable on horseback.

- The trousers correspond with the domestication of horses, a seminal event in human history that brought Europe and Asia closer together.

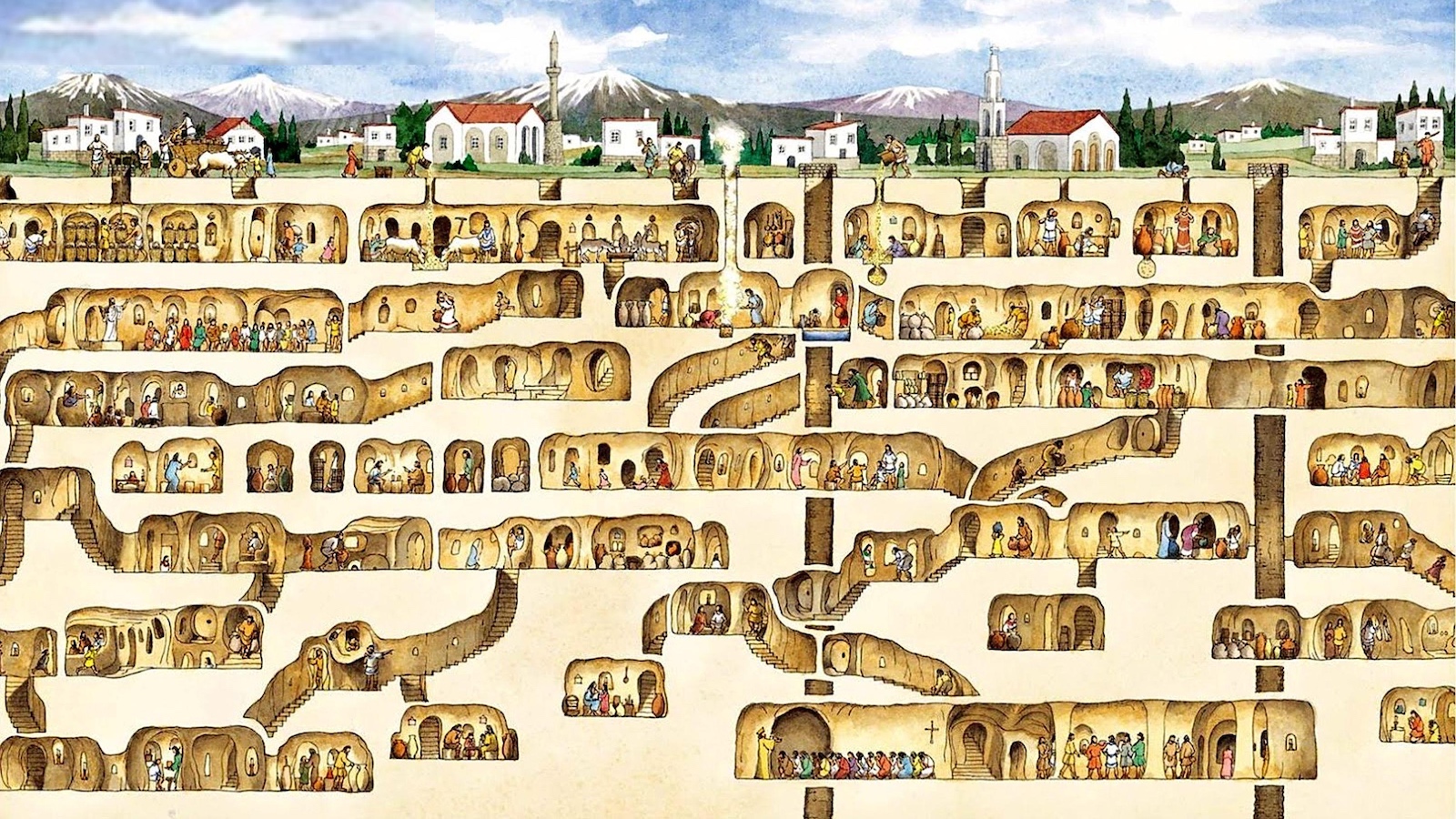

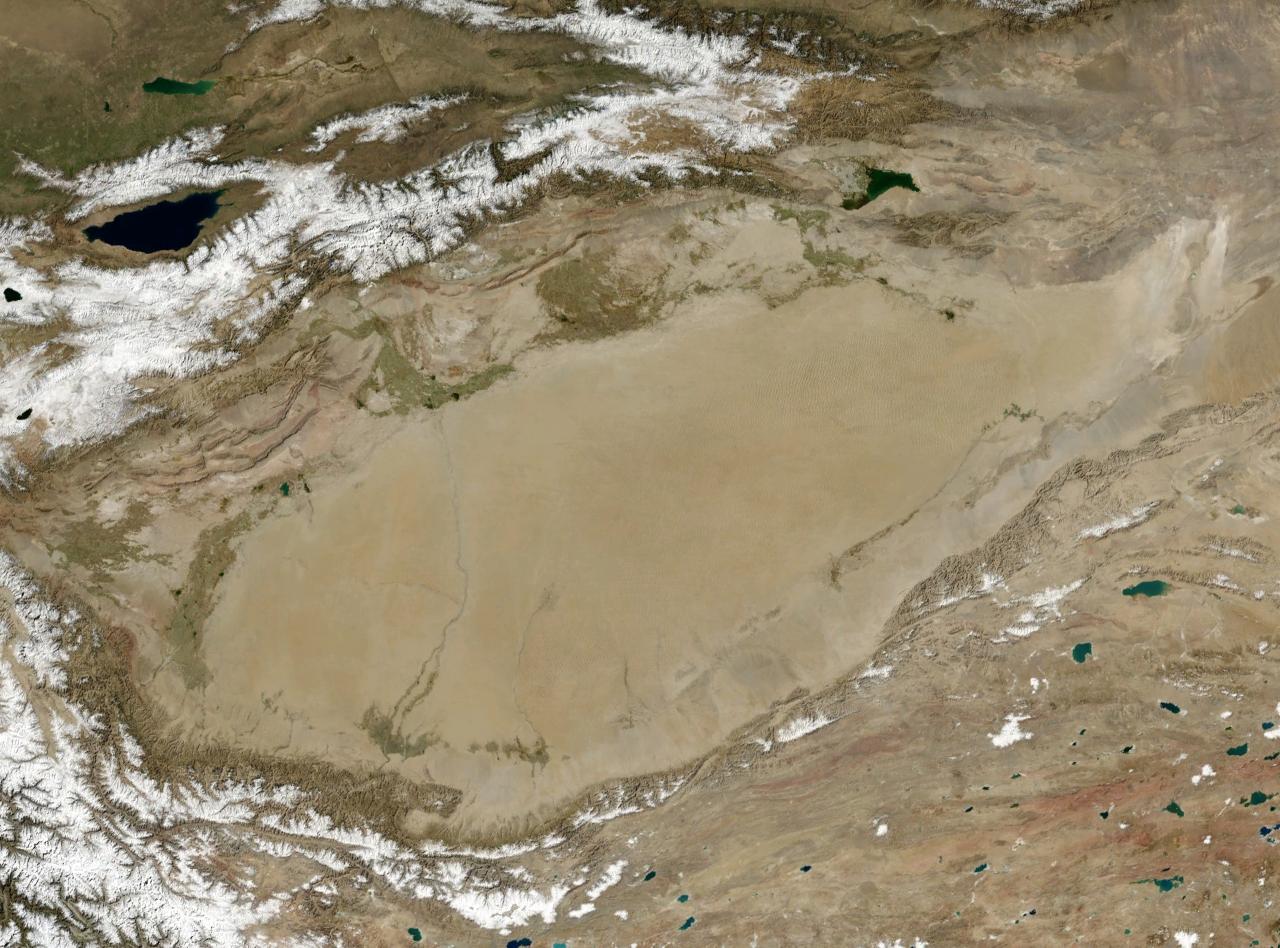

In the early 1970s, Chinese archaeologists stumbled upon the mummified remains of some 500 individuals who had been laid to rest more than three millennia ago in the Yanghai cemetery, located in the Tarim Basin, a vast area in northwest China that has yielded many important discoveries regarding the history of ancient humans, from the remains of the Xinjiang region’s earliest-known settlers to the origins of fashion.

One body in particular caught the attention of the researchers, not just because it had been impeccably well-preserved but also because it was, even after all this time, still impeccably dressed. The Turfan Man, named after the nearby Chinese city of the same name, had gone into the grave wearing his Sunday best, sporting a poncho, soft leather boots, and a woolen headband decorated with bronze discs and seashells.

This mummified corpse had quite the wardrobe, even when compared to the pharaohs of Egypt. Most remarkable of all were the Turfan Man’s trousers, which consisted of two tapered leg pieces connected at the top by a crotch piece that seems to have provided the wearer with great mobility. The design was as intricate as that of modern-day, factory-fabricated denim jeans, and just as durable.

The ultimate origin of Fashion Week

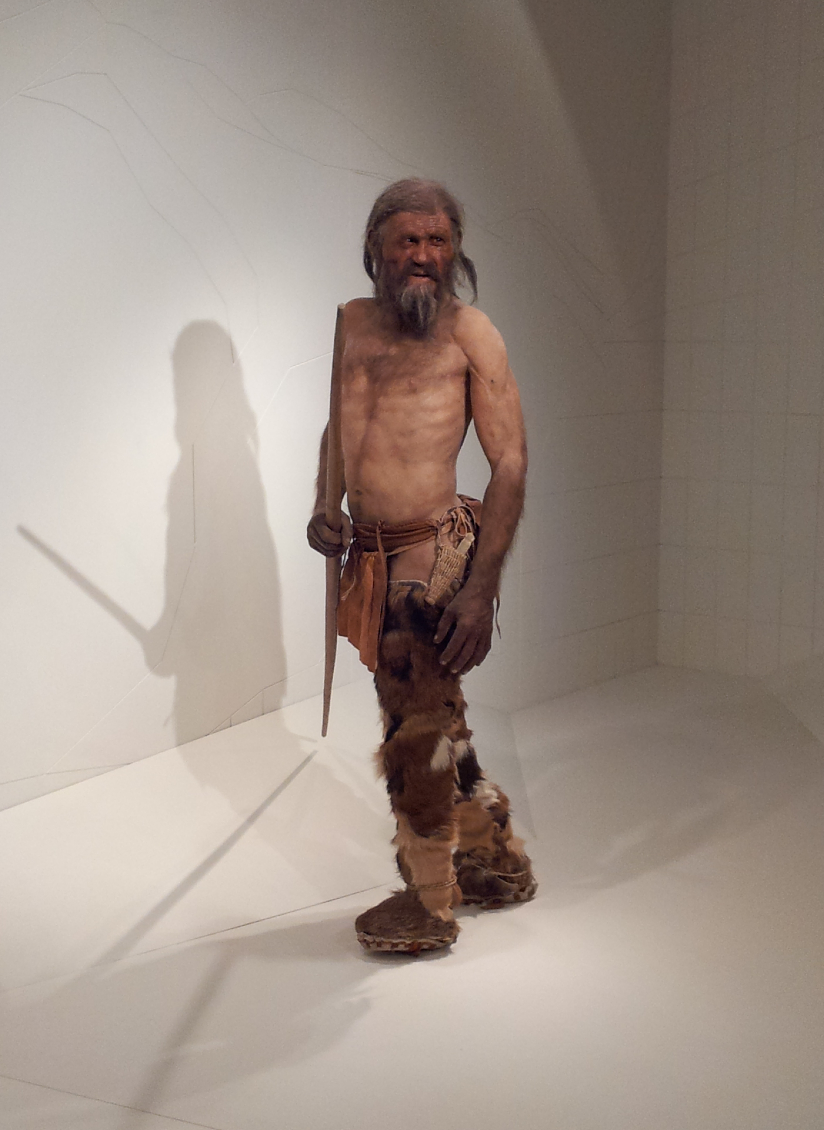

Dated to at least 3,200 years old, the Turfan Man’s trousers are believed to be the oldest pair of trousers yet discovered, giving researchers a rough estimate for when this now indispensable piece of clothing was first invented. “Previously,” reports Science News, “Europeans and Asians wore gowns, robes, tunics, togas or — as observed on the 5,300-year-old body of Ötzi the Iceman — a three-piece combination of loincloth and individual leggings.”

Fashion is a key aspect of human history, yet its origins and significance are often overlooked. To some extent, this is due to our own biases. Because clothing is viewed as “synonymous with frivolity, excess, and luxury,” costume scholar Olivia Warschaw writes in an article on the philosophy of fashion studies, it tends to be considered less important in the grand scheme of things than factors like economics, politics, science, philosophy, or the fine arts.

On top of this, most textiles don’t preserve half as well as bones do, making it very challenging for archaeologists to sketch a clear picture of how fashion trends developed in the ancient world. Still, fashion is a cultural universal, and the evolution of primordial garments tells us a lot about the equally primordial people that wore them, from the ideas behind their cultural and religious practices to their movement across different areas of the globe.

Fashion studies: untangling the world’s oldest pair of pants

Determining when the Turfan Man’s trousers were made proved to be a whole lot easier than determining how they were made. Carbon dating and other forms of analysis can provide us with fairly precise age estimates, but the atoms themselves do not reveal anything about the techniques or influences that ancient craftsmen relied on to put them together to create a pair of pants.

To that end, archaeologist Mayke Wagner, scientific director of the Eurasia Department of the German Archaeological Institute, assembled an Avengers-like team of geologists, chemists, and fashion designers to give the Turfan Man’s fabled fashion a closer look. Their goal was to study the weaving methods in order to recreate the original production process and, by doing so, untangle the garment’s biggest secrets.

Wagner’s team presented their research findings in the March 2022 issue of Archaeological Research in Asia. In short, they learned that the Turfan Man’s trousers were made with the help of a single device and that its craftsmen used as many as four different weaving techniques. Two of these were found to be unique to this particular pair of pants. They were termed “Yanghai weft twining” and “Yanghai dovetailed twill tapestry.”

Seeing that the fabric of the Turfan Man’s trousers showed no signs of cutting or knitting, Wagner’s researchers speculated that the trousers had been woven rather than stitched together. Their suspicions soon proved correct; an initial examination of the ancient garment revealed that parts of the trousers were woven together with a technique known as twill weave.

Twill is a type of textile weave that produces a diagonal pattern of parallel ribs, making the fabric less rigid and more elastic, thus allowing the wearer greater mobility. Considering that the people buried at Yanghai belonged to a culture of herders and horse riders, this discovery is not all that surprising.

What is surprising, however, is that twill weave was still a novelty back when the Turfan Man’s trousers were made. According to Karina Grömer, a textile archaeologist from the Natural History Museum Vienna, the oldest known fossil evidence of twill weave comes from pieces of woven fabric recovered from a salt mine in Austria, far removed from China’s Tarim Basin. These textiles were estimated to be at least 200 years older than the Turfan Man’s trousers.

Like modern-day jeans

The rarity of twill weave raises important questions about the cultural influences that may or may not have informed these ancient Chinese craftsmen. It was also a testament to their skill. Modern-day denim jeans, revered for their durability, use the same technique. “This is not a beginner’s item,” Grömer, who wasn’t part of Wagner’s study but studied the garment some years ago, told Science News. “It’s like the Rolls-Royce of trousers.”

A different kind of weaving, known as tapestry weaving, was used for the cloth around the knees. Compared to twill weaving, tapestry weaving creates a thicker layer of fabric that, in this case, would have served to protect the wearer’s joints when riding on horseback. Finally, a third weaving method was used on the upper border of the trousers, creating a sturdy but considerably flexible waistband to keep the pants in place.

While fashion designers could easily recognize the weaving patterns, they were clueless as to the equipment that the craftsmen may have used. No weaving tools were ever found at or near Yanghai, and to this day, archaeologists have no idea what an ancient loom from this region could have looked like. Wagner suggests that the craftsmen may have used a loom that could be operated from a seating position, but this is little more than speculation.

According to Wagner’s study, their best shot is to produce more replicas using different ancient and contemporary weaving devices and determine which of these replicas is closest to the original. In order to make their replica as faithful as possible, the researchers employed an expert weaver, who used the same material as the ancient Chinese craftsmen: yarn spun from coarse-wooled sheep. The same material would be used in future replicas.

Stitching together the past, one fiber at a time

Textile archaeology gives new meaning to the expression “clothes make the man.” The way that clothing was made and the reasons for which it was worn teach us a lot about ancient civilizations, especially those without their own systems of writing. The Turfan Man was quite a trendsetter as, a few short centuries after his death, trousers were being worn by mobile groups throughout Eurasia.

The rising popularity of trousers, other archaeological studies have shown, corresponds with the emergence of horseback riding. Small wonder. As mentioned, the twill weave and flexible crotch piece of the Turfan Man’s trousers combined a tight fit with greater mobility — garment qualities that come in handy when you have to climb and ride horses on a daily basis.

The Yanghai craftsmen had refined the crotch piece to perfection. While other trousers found in Central Asia connected the leg pieces with a square crotch piece, the Turfan Man’s crotch piece was wider at the center compared to its ends. To better understand the purpose of this design, Wagner’s team tested the replica on a man riding a horse bareback and found that the trousers fit comfortably while still allowing the rider to firmly clamp his legs around the horse.

Ancient fashion

Just as the shape of the crotch piece tell us something about the Turfan Man’s lifestyle, so too can the patterns on the garment give us an idea about the cultural and economic relations of his community. As Wagner’s study points out, the same interlocking T-pattern decorating the knees has also been discovered on bronze vessels from China as well as pottery from Siberia and Kazakhstan.

The fact this curious pattern arose simultaneously in both Central and East Asia indicates that the two regions, while separated geographically, were very much connected to each other through sustained contact. Fittingly, this coincided with the arrival of West Eurasian herders, who migrated into Asia on horses that, once domesticated, made it easier to travel to and between remote locations.

Another pattern found on the Turfan Man’s trousers, that of a stepped pyramid, bears strong resemblance to patterns that appear on pottery produced by the Petrovka culture of Central Asia that thrived between 3,900 and 3,750 years ago, not to mention the architectural designs of southwestern Asia and Middle Eastern societies from more than 4,000 years ago.

Numerous archaeological discoveries, from the eastward migration of Eurasian herders to the possible origins of twill weaving in Eastern Europe, suggest that the creation of the world’s first pair of pants was the result of cultural and economic exchange between peoples that, at that point in history, had hardly come into contact with one another.

For this reason, Michael Frachetti, an anthropologist from Washington University in St. Louis, has referred to the Turfan Man’s trousers as “an entry point for examining how the Silk Road transformed the world.” Wagner couldn’t agree more. “Eastern Central Asia,” the archaeologist told Science News, “was a laboratory where people, plants, animals, knowledge, and experiences from different directions and sources came… and were transformed.”