- Climate-related catastrophes have struck the world in several previous eras, such as gigantic volcanic eruptions.

- From the 1300s to the 1800s, four major climate catastrophes reshaped global religion.

- We must be wary that religion or ideology combined with external shocks like climate change can cause war or revolution.

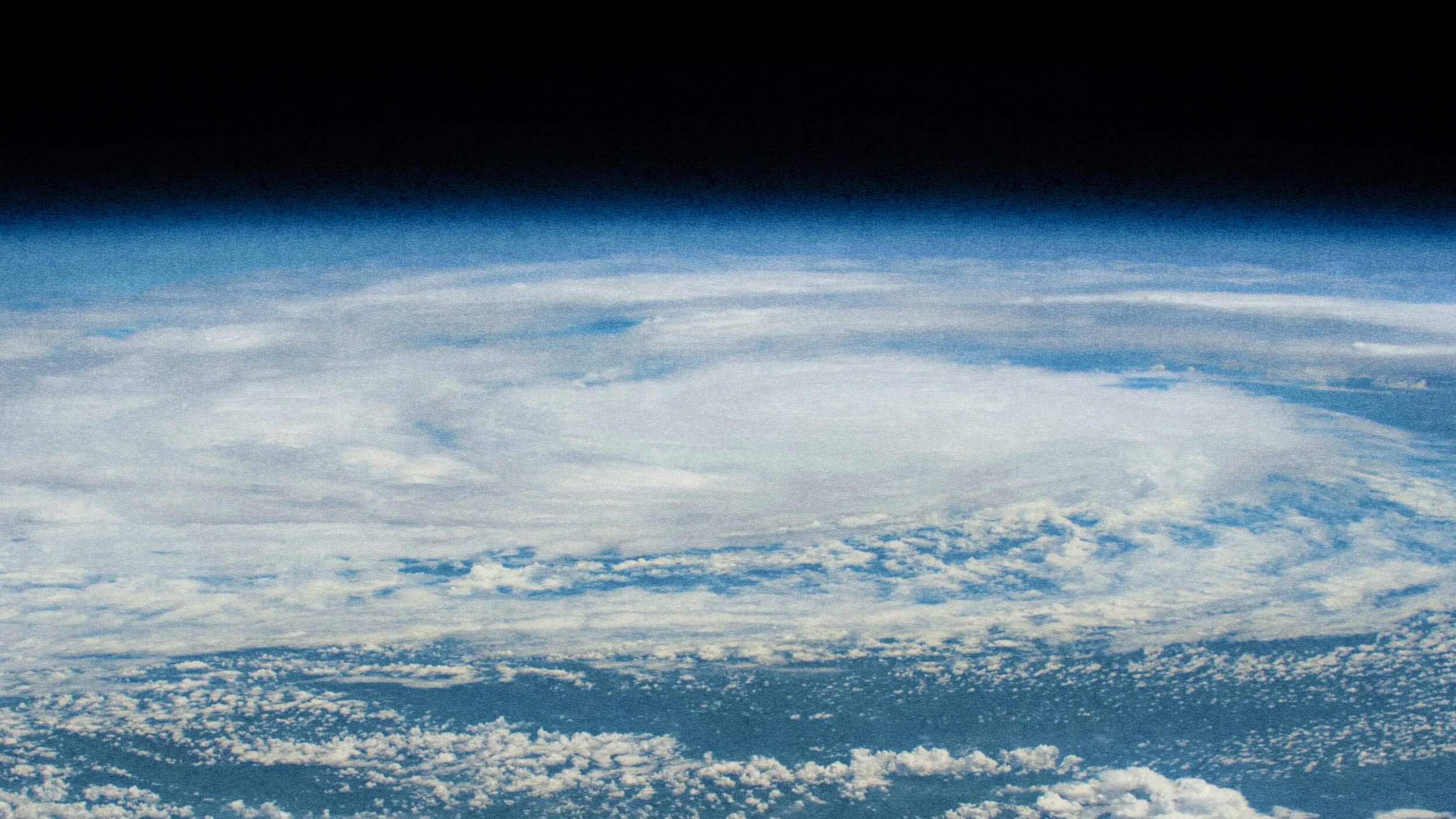

We presently hear a great deal about global climate change and the disasters it threatens in the imminent future. Within a few decades, large sections of the human race, chiefly in nations of the global South, will regularly be suffering widespread hunger and acute water shortages, as dramatic environmental changes threaten the survival of state mechanisms in many nations. Together, these changes will drive mass migrations, and create refugee crises on a dreadful scale. So much is familiar enough. But with fair confidence, we can also predict that such changes are all but certain to have religious consequences, in terms of driving conflicts between faiths, and also by sparking new movements, and conceivably even whole new faiths.

How can anyone make such an assertion? Because in different ways, climate-related catastrophes have struck the world in several previous eras, whether because of gigantic volcanic eruptions or else sudden shifts in the intensity of the energy being released by the sun. In contrast to the climate change we are now living through, those past experiences were transient and temporary. But whatever the causes, such events have been deeply traumatic, and in every case, they have resulted in massive and wide-ranging religious transformations. How could they not?

It is difficult to imagine that catastrophic climatic changes might not inspire religious responses and even revolutions.

Time and again, climate convulsions have been understood in religious terms, through the language of apocalypse, millennium, and judgment. Often too, such eras have been marked by far-reaching changes in the nature of religion and spirituality. This does not mean that climatic conditions directly caused such outbreaks or currents; rather, they created an atmosphere in which those changes could manifest themselves, and in historical terms, this happened very suddenly. Depending on the circumstances, the response to climatic variations might include explosions in religious passion and commitment, the stirring of mystical and apocalyptic expectations, waves of religious scapegoating and persecution, or the spawning of new religious movements and revivals. In many cases, such responses have had lasting impacts to the point of fundamentally reshaping particular faith traditions.

From those eras have emerged passionate sects — some political and theocratic, some revivalist and enthusiastic, others millenarian and subversive. The movements and ideas emerging from such conditions might last for many decades and even become a familiar part of the religious landscape, although with their origins in particular moments of crisis, they often are increasingly consigned to remote memory. By stirring conflicts and provoking persecutions that defined themselves in religious terms, such eras have redrawn the world’s religious maps and created the global concentrations of believers that we know today.

Four climatic catastrophes that transformed religion

In my current book Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith, I particularly highlight four such transformational eras, which combined to create so many of the religious realities we know today. The first of these is the early fourteenth century, especially the years between 1310 and 1325, a time of abrupt global cooling that marked the onset of the Little Ice Age. Societies around the world suffered times of shocking paranoia and conspiracy-mongering. They responded with murderous persecutions of minorities and dissidents, leading to purges and expulsions on an appalling scale. Whole populations suffered bitter times of exile and diaspora, and those changes did much to create our familiar maps of the great faiths and their geographical concentrations. This was the time when large portions of the Jewish population were driven from Western Europe to the eastern fringes of the continent, where their descendants were concentrated until the last century. In the Middle East, meanwhile, Christians were reduced to the status of a despised minority.

About 1560, the Little Ice Age entered a new and brutally cold era, when social strains threatened the survival of social and political orders. The resulting unrest and disaffection took multiple forms, but it especially manifested in one notorious form of social paranoia: the witch-hunts, which reached their peak in Europe. At the same time, the 1560s witnessed a dramatic religious transformation within Christianity, affecting both its Catholic and Protestant dimensions. The fast-growing Calvinist movement represented a revolutionary current that threatened the near-overnight razing of ancient religious ways. On the other side, reformed and restructured Catholicism became equally hard-edged and confrontational — a comparable faith of crisis. The Christian world entered a new and much harsher period of polarization as revolutionary religious change detonated savage wars.

The third era stretches from 1675 through the end of the 17th century, which constituted one of the very coldest and most ruinous periods of the Little Ice Age, an era of lethal famines. Rebellions, revolutions, and civil wars proliferated, inciting larger struggles that led to the dramatic reduction of Islam as a force in Europe. Meanwhile, the cumulative crises generated savage persecution of religious minorities. But unlike the 14th century, Europeans now lived in a world of sea travel and far-flung colonial possessions, and persecuted populations amply exploited these opportunities to seek safe haven. Religious dissidents from Germany and the British Isles flocked to the new world, as a generation of climate refugees built new homes, especially in Pennsylvania. Settlements in foreign lands far from the motherland offered the prospect of new concepts of religious liberty, opening a dramatic new phase in attitudes to religious freedom and spiritual experimentation.

The fourth era of extraordinary Arctic cold struck the North Atlantic world between 1739 and 1742, and this created the desperate conditions that formed the backdrop of the revivals of the Great Awakening and the emergence of Anglo-American evangelicalism. And the story can be carried into the 19th century, when disasters like the Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815 sparked new apocalyptic expectations.

Climate + Religion = Revolution?

If the role of climate change on Christian history is obvious enough, the same factors likewise had their impact on important movements within other traditions, including Buddhism and Islam. Any historical account that ignores or underplays that climate dimension is lacking.

That history must come to mind when we contemplate the global climatic pressures that are predicted for the coming decades. Based on extensive past experience, we can imagine many ways in which the response to those circumstances might take religious forms. We could foresee the rise of new apocalyptic movements, as well as the spread of bitter religiously based animosity and conflict. When we look at contemporary developments in both Islam and Christianity, and at interfaith conflicts across Africa and Asia, it is difficult to imagine that catastrophic climatic changes might not inspire religious responses and even revolutions.

When we trace the historical impact of climate-related change in the religious realm, we see auguries of our likely futures.

Philip Jenkins was educated at Cambridge University and for many years taught at Penn State. He is presently Distinguished Professor of History at Baylor University, where his main appointment is in the Institute for Studies of Religion. His latest book, Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval, was just published by Oxford University Press.