Like birds and mammals, most dinosaurs were warm-blooded

- For decades, paleontologists have tried but failed to determine whether dinosaurs were cold- or warm-blooded.

- Scientists announced the discovery of a new method to measure dinosaurs’ metabolic rates. We can interpret a dinosaur’s metabolic rate by measuring the amount of metabolic waste in a dinosaur’s bone.

- The study suggests that many, but not all, dinosaurs were warm-blooded, providing new insights into the lives of these enigmatic creatures.

Researchers have worked to understand the metabolism of dinosaurs for many years. Paleontologists yearn to know whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded, like birds and mammals, or cold-blooded like reptiles.

A group of scientists this year announced a major breakthrough on the topic. The researchers reported that they were able to use organic molecules found in fossils to determine a dinosaur’s metabolic rate. The international group of researchers, from Yale University and the Universidad Complutense in Madrid, Spain, used their method to study bones spanning the major groups of dinosaurs. They reported their findings in May in the journal Nature. The results show that most dinosaurs were warm-blooded, and provide evidence that could begin to close the book on decades of research into the matter.

Metabolism 101

We all have friends who brag about their “high metabolic rate” as they help themselves to a second dessert portion. But relative to most of the animal kingdom, all of us — you as well as your energetic, hungry friend — have a fast metabolism, a term that describes the chemical reactions that convert the oxygen we breathe into chemical energy.

Because we are warm-blooded, or endotherms, we use some of this chemical energy to maintain a consistent body temperature that allows our basic physiological processes to keep going while we remain active in a variety of environments and climates. On the other hand, cold-blooded animals — the ectotherms — do not use their metabolism to maintain a constant body temperature. Instead, they rely on environmental heat and regulate their body temperature with behavioral adaptations like sun-basking.

Along with other mammals, birds are also warm-blooded. In fact, birds boast the highest measured metabolic rates of any extant organism and could school your hungry friend any day of the week. Reptiles, on the other hand, are cold-blooded.

The metabolism of dinosaurs — reptiles that evolved into birds — has been a mystery for years. Scientific efforts to determine whether they were cold-blooded or warm-blooded creatures have mostly failed. But the researchers led by Yale’s Jasmina Weisman found that the metabolic signature of dinosaurs has been written in their fossils all along.

Breaking it down

One of the critical processes in warm-blooded creatures is the breakdown of fats and sugars into chemical energy. This process produces organic, protein-based wastes that survive in deep time and are preserved well in fossilized tissue — and also in the tissues of modern animals to whom the fossils can be compared.

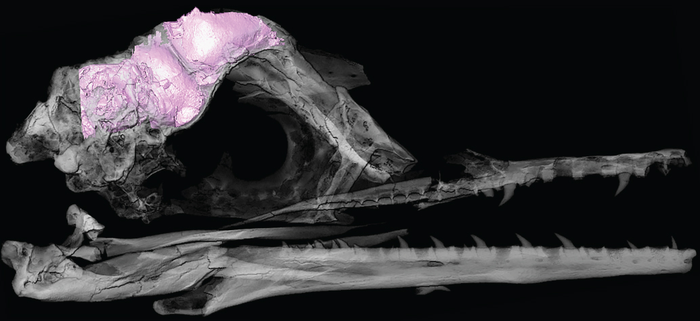

The researchers searched for these organic molecules using infrared spectroscopy. The method is non-destructive, a bonus since it allows the researchers to leave the bones intact. Higher concentrations of the targeted chemicals indicate a faster metabolism, suggesting that the fossil’s owner was a warm-blooded creature.

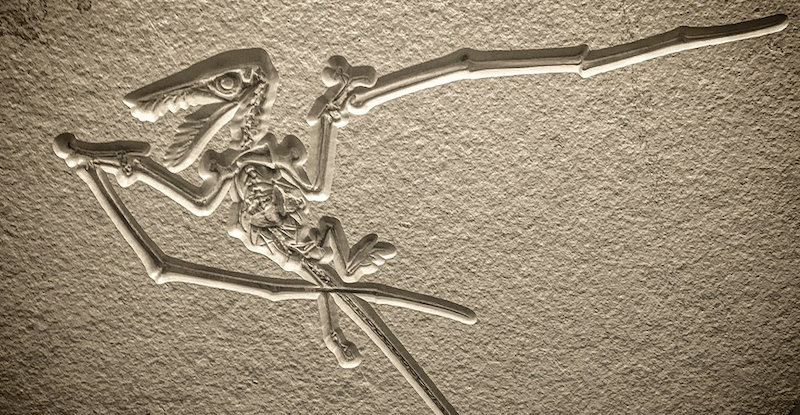

The team created an equation that measures the number of chemical signals in the femurs of fossils and tests it against the number of similar molecular byproducts in the tissue of modern animals whose metabolic rates we already know. In total, they analyzed 55 femurs from dinosaurs, pterosaurs (flying cousins of the dinosaurs) and plesiosaurs (marine relatives of dinosaurs), as well as modern birds, mammals, and lizards.

Dinosaur metabolisms differed

In general, the dinosaurs had levels of organic waste that indicated high metabolic rates. The team looked at two big groups of dinosaurs — the saurischians (which means “lizard hips”) and the ornithischians (“bird hips”). Some of the ornithischians, like the famous Triceratops and Stegosaurus, had low metabolic rates comparable to modern cold-blooded animals. But the saurischians of Jurassic Park fame (think Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus) were warm-blooded.

This information helps researchers better visualize the lifestyles of some of the most emblematic dinosaurs. Warm-blooded and cold-blooded animals live very different lives. Think of a cheetah stalking its prey versus a snake lounging in the sun. Likewise, cold-blooded dinosaurs needed warm temperatures to be active, whereas warm-blooded dinosaurs would need to eat a lot, but could remain active throughout the year.

The researchers also mapped the metabolic rates onto a phylogenetic tree that shows how dinosaurs, birds, and mammals are related. The tree shows that high metabolic rates evolved independently multiple times. For example, modern birds inherited their metabolic toolkit from ornithodirans, who might have had metabolic rates higher than any organism alive today.

Did dinosaurs’ metabolisms determine which survived?

When an asteroid six miles wide struck the Yucatan peninsula 66 million years ago, the disruption that ensued wiped out an incredible portion of life on Earth. The only dinosaurs to survive were part of the beaked, avian lineage, and they became modern birds. Some scientists have wondered whether these dinosaurs were warm-blooded like their modern kin and could therefore adapt more quickly to the sudden environmental change. By contrast, any cold-blooded creature would die, as life-giving sunlight was blocked by the tons of dust the asteroid released into the atmosphere.

However, now we know that pterosaurs and non-avian ornithodirans had elevated metabolic rates that suggest a warm-blooded metabolism — and these creatures all perished. So the data also suggests that something other than metabolic flexibility sealed the fate of terrestrial dinosaurs, prompting more questions into how one of our favorite mysteries, the extinction of dinosaurs, unfolded.