A tale of two shipwrecks: Endurance and Atlanta

- The discovery of Shackleton’s Endurance in the Weddell Sea has sparked global interest in shipwreck recovery.

- Bruce Lynn, executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Society, explains the logistics of searching for sunken vessels in deep, dark water.

- Ultimately, every shipwreck is its own tragedy, a completely unique story about brave people who lived and, in some cases, died on open water.

On October 26, 1914, the famous explorer Ernest Shackleton and his crew left the South Atlantic whaling port of Grytviken on the island of South Georgia and set sail for the Weddell Sea. Their goal was to reach the South Pole and cross the Antarctic continent: something no explorer in human history had — at that point in time — managed to do.

For a short while, it seemed as though Shackleton’s voyage would end in success, not shipwreck. Thanks to its rounded hull, their ship — christened the Endurance — was able to work its way through thick layers of pack ice. The further the crew waded into Antarctic waters, the thicker this ice became. Before long, their ship was moving at a pace of less than 30 miles per day.

In January, heavy winds caused the pack ice to compress, surrounding the Endurance from every direction. The crew attempted to hack their way through the ice, but when the ship failed to gain the momentum necessary to free itself, Shackleton decided that it was unwise to waste any more coal and manpower.

The expedition had come to a grinding halt. Its boilers extinguished, the Endurance was forced to wait for the ice to disperse naturally, which did not happen. Winds rose and temperatures fell further still, heralding a blizzard that continued into July. After getting stuck yet again, the ship’s masts collapsed and the bow was crushed.

On November 21, 1915, pressure waves crashed down upon the Endurance, causing the ice to separate. Unable to keep afloat, the heavily damaged ship sank into the depths below. Against all odds, Shackleton and his crew survived the ordeal and returned to civilization, but their trusted vessel had turned into a shipwreck and was lost forever.

Shackleton’s Endurance rediscovered

Or so it seemed. Earlier this month, a research expedition organized by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust announced that they had located the remains of the Endurance. In a statement that shocked maritime researchers and sparked the public’s imagination, the mission’s director of exploration, Mensun Bound, called the discovery a “milestone in polar history.”

Bound’s discovery team started from Cape Town on a research and logistics vessel dubbed the Endurance22 and set course for the Weddell Sea. Once the icebreaker reached the point where the original Endurance was believed to have sunk, they used underwater search vehicles to locate the wreck, which had rested at depths of 3 kilometers for more than a century.

Thanks to environmental conditions, the Endurance was preserved extraordinarily well. “It would appear that there is little wood deterioration,” Dr. Michelle Taylor, a polar biologist at the University of Essex, told the BBC, “inferring that the wood-munching animals found in other areas of our ocean are, perhaps unsurprisingly, not in the forest-free Antarctic region.”

While many people would love a chance to see the Endurance in person, the wreck won’t be exhibited in a museum any time soon. Doing so would violate the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed to regulate international relations regarding Antarctica, and which designates Shackleton’s ship as a historic monument that cannot be removed from its current position.

The Endurance quickly became one of the most famous shipwrecks of all time, second only to the Titanic. So, let’s do a deep dive (no pun intended) into the fascinating logistics of recovering centuries-old shipwrecks.

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society

To learn more about the nitty-gritty of shipwreck preservation, Big Think talked to Bruce Lynn, the executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society in Michigan. Operating from the cape of Whitefish Bay, the Historical Society is dedicated to exploring, documenting and — where possible — exhibiting ships that met their fate in the waters of the Great Lakes and beyond.

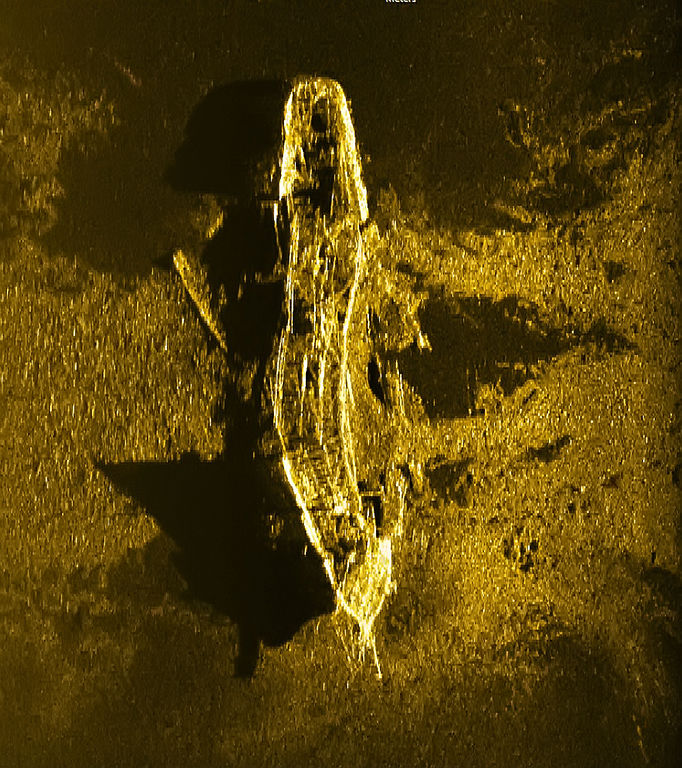

During the summer of 2021, the Historical Society mapped out more than 2,500 miles of Lake Superior using side scan sonars developed by Marine Sonic Technology, a company that provides equipment for first responders, federal agencies, military services, coast guards, archaeologists and professional as well as amateur treasure hunters.

The sonar is shaped like a torpedo, which is submerged into the lake and towed by ship across a preplanned grid. Along the way, researchers take note of any objects that the sonar might pick up. If an object seems interesting, the crew will return to the marked location at a later date and drag the sonar across once more to try to get a clearer picture.

If the object does not appear to be a large rock, the crew will use a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to check it out for themselves. The ROV is equipped with high definition cameras, allowing researchers to get a clear visual at depths of over 800 feet. Even though most objects actually do turn out to be rocks, there is no way of knowing for sure until the ROV has taken a look.

“Shipwreck hunting can be tedious,” states the Historical Society’s website, something Lynn confirms. “It’s not always exciting, being out on the water,” he tells Big Think. “We jokingly call it ‘mowing the lawn.’” Workdays often last 13 to 14 hours, and plans are frequently upended by volatile weather that can inhibit and even damage the team’s costly machinery.

The tragedy of the Atlanta

Of course, every discovery more than makes up for all that tedium. Recently, on March 3, the Historical Society announced one of its most exciting discoveries to date. As a direct result of their summer project, the Society managed to locate the wreck of a ship that went missing more than 130 years ago, when it ran into some very bad weather 35 miles off the Michigan coastline.

The vessel in question is the Atlanta, a 172-foot schooner-barge that was being towed across Lake Superior by another ship while carrying a load of coal when, on May 4, 1981, it was struck by a northwestern gale. The Historical Society’s newsletter reconstructs the shipwreck that followed in striking, almost literary terms:

“The storm was too much for the towline which snapped, and with no sails, the Atlanta was soon at the mercy of the lake, and the crew took to the lifeboat. They pulled at the oars for several hours and eventually came within sight of the Crisp Point Life-Saving Station. While attempting to land their small boat near the station, it overturned and only two of the crew made it safely to the beach.”

Just as with Shackleton’s Endurance, the frigid waters of Lake Superior ensured the Atlanta shipwreck was preserved in near-perfect condition. From the pump and steering wheel down to the toilets, many elements of the ship’s original construction remained intact. Even the vessel’s nameboard — an elegant and ornate piece of craftsmanship — was, after all this time, still legible.

The state of the Atlanta corresponded with the eye-witness accounts that were given by the incident’s two surviving crewmates, who claimed that the storm had torn off each and every one of the ship’s three masts. Pictures taken by the ROV and published on the Historical Society’s website confirmed that the masts were no longer attached to the vessel.

The importance of shipwreck preservation

Despite the amount of work that went into the recovery, the Atlanta was relatively easy to track down. That is because, unlike other shipwrecks, the sinking of this particular vessel was documented extensively by media outlets of the time. Their detailed coverage, said Lynn, gave the team a rough idea of where they should start looking.

The Atlanta, like the Endurance, will not be removed from its final resting place thanks to a Michigan state law that prevents organizations from salvaging “abandoned property on the bottomlands of the Great Lakes.” Instead, the Historical Society will continue studying the wreck to create and inform future exhibitions at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

As pleased as Lynn was with his team’s latest find, he confesses that he also felt just a tiny bit conflicted when news of Shackleton’s Endurance came to overshadow that of the Atlanta. At the same time, he cannot wait to hear how Bound’s recovery team managed to track down such a famous wreck in such an infamously inhospitable and remote environment.

Ultimately, it’s not a competition. Every shipwreck is its own tragedy, birthing unique and equally important stories. Similarly, every research endeavor and museum exhibition is a means of keeping alive the memory of people who worked and — in some cases — died on open water, not to mention the history of the vessels that carried them.

“Most people only know of one Great Lake Shipwreck,” Lynn concludes, “the Edmund Fitzgerald. I always like to point out that there are 6,000 shipwrecks at the bottom of the lakes, and they are all their own Fitzgeralds or Titanics.” As Lynn prepares to search for French minesweepers that sank during World War I, he and his team, like Shackleton, hope for some good weather.