How the crusades spawned the world’s first financial services company

- The Temple Church of London allowed Christian pilgrims to deposit funds in England and withdraw them in Jerusalem.

- The organization was run by the Knights Templar, an order of religious knights created to protect the Holy Land from Muslim invaders.

- The Templars offered their financial services to the general public, meddling in international politics and shaping the future of Europe’s economy.

Europeans first began making pilgrimages to Jerusalem after the First Crusade in 1099, which was fought not only to reclaim the Holy Land from the Islamic conquest of the Levant, but also to open up an overland route for Christians looking to visit the birthplace of their faith.

Even with this route secured, such visits were filled with danger. If all went well, the journey from Italy to Jerusalem took about two months to complete: about as long as it took for English migrants to reach New York during the colonial era. Usually, though, pilgrimages took longer than two months because pilgrims were routinely slowed down by war, sickness, and robbers — threats that only grew bigger as they ventured farther from home.

Robberies were particularly commonplace, and for good reason. Pilgrims had to carry with them enough money to pay for food and shelter on the way. They were also generally unarmed and untrained, making them the perfect target in the eyes of a bandit.

For most European pilgrims, getting robbed was simply a risk they had to take if they wanted to reach the place where Jesus Christ was believed to have been crucified and resurrected. British travelers, however, had a way to minimize that risk. In London, there was an organization known as the Temple Church, where pilgrims could deposit a portion of their savings. In return they were given a letter of credit that they could use to withdraw their savings once they reached Jerusalem.

The services of the Temple Church made the pilgrimage to the Holy Land a lot safer. Now pilgrims did not have to carry as much money with them when they set out on their journey, reducing the odds of attracting robbers. Plus, if they were robbed, they would be able to replenish their finances at their destination.

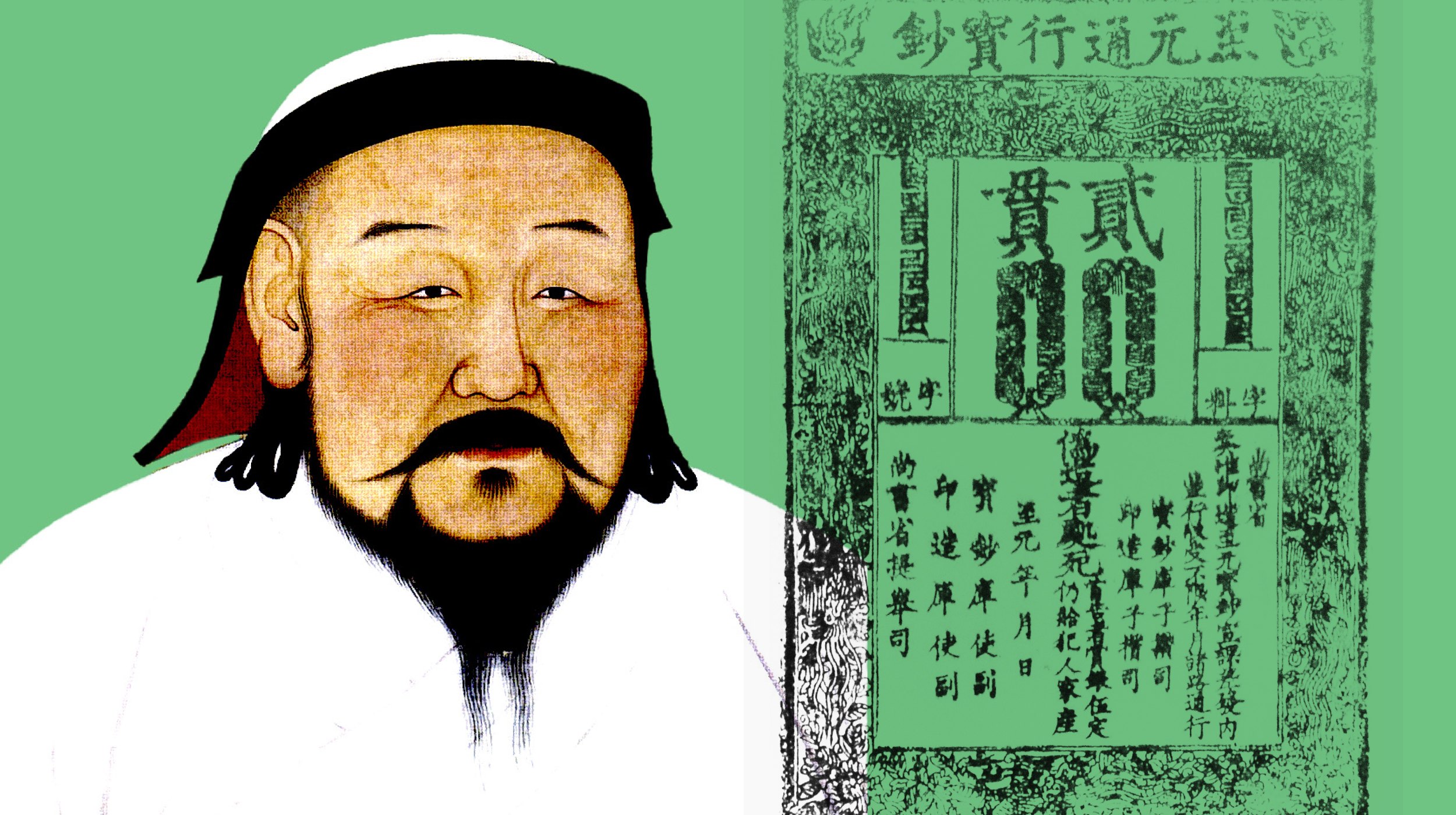

In an article for the BBC, Financial Times columnist Tim Harford called the Temple Church “the Western Union of the crusades.” Historians often refer to the organization as the world’s very first bank, preceding Italy’s Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena by several centuries. The Temple’s concept of a letter of credit was not entirely original; in the 7th century CE, Chinese merchants could deposit their coin rings at agencies in exchange for promissory notes. The key difference was that these agencies were operated by the government of the Shang dynasty, while the Temple Church was a privately owned enterprise.

The Knights Templar

The founders of the Temple Church were none other than the legendary Knights Templar. Also known as the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Order of Solomon’s Temple, among other names, the Templars were one of several Christian military orders that sprung up across Europe to ensure safe passage to Jerusalem. The order was founded sometime around 1118, after the First Crusade, and its members fought in subsequent ones as an elite force. In between battles, they built and manned fortifications throughout the city: a means of strengthening both Christian and European presence in the Holy Land.

But the Knights Templar weren’t just excellent fighters, they were also clever financiers. This side of the order is often overlooked today, which is surprising, considering the monumental role that the Temple Church played in the evolution of Europe’s financial system.

Before we take a closer look at that role, it is worth asking why the Templars of all the people in London ended up becoming bankers. In her article, “The Financial Relations of the Knights Templars to the English Crown,” Eleanor Ferris speculates that the order’s financial services may have been born out of the “common medieval practice of depositing objects of value in consecrated places for security during times of trouble and tumult.” Aside from conventions, the Temple Church happened to be a highly fortified building, constructed by skilled engineers, defended by highly trained soldiers, and located at one of the most strategic places in the city. It was, in other words, a perfect vault.

The financial services of the Knights Templar were not just available to Christian pilgrims, but the general public as well. Ferris mentions that “all classes of persons who possessed treasure” turned to the Temple Church to store their gold, silver, and jewels during the 13th century. The order’s list of clients also included the English nobility, who stored taxes and feudal dues in addition to their personal wealth, as well as the pope. The latter deposited papal subsidies and, during the crusades, requested grants to defend the Holy Land from Muslim invaders.

Aside from storing wealth for individual clients, the “Western Union” of medieval Europe could also transfer funds from the account of one person to that of another. At one point, the Knights Templar obtained 40,000 marks from Falkes de Bréauté, a soldier in service of King John of England. When de Bréauté was exiled for staging an unsuccessful rebellion, the Templars turned over his money to the kingdom. Five years later, they transferred to the account of crown prince Edward some 10,000 marks that were originally entrusted to them by his own subjects.

How to finance a crusade

The Temple Church could not have been established without the crusades, whose financial, logistical, and military demands exposed the limitations of Europe’s preeminent economic structure: the feudal system.

According to a dissertation written by Ronald Grossman for the University of Chicago titled “The Financing of the Crusades,” these limitations first came into focus during the Norman Conquest of England, which occurred several years before Christian soldiers would march into the Levant. The Norman conquest was a crusade in and of itself insofar as William of Normandy required his vassal lords to march their soldiers into a territory far beyond the former’s jurisdiction. The vassal lords, unwilling to provide the unprecedented amount of time and manpower needed for the invasion, argued that they could not be compelled to take up arms based on their age-old feudal ties alone.

“Their obligations to William,” writes Grossman, “they asserted, ended where the sea began.”

Forced to come up with a new kind of incentive to raise an army, William the Conqueror promised to share a substantial amount of riches from the island they were about to take over. The vassal lords complied, and the rest is history.

The holy wars unfolded along similar lines. Although Pope Urban II argued that salvation was the primary reward for partaking in the deadly crusades, and Gregory VIII called on his crusaders to reject “luxury and ostentation (…) as would befit people doing penance for their sins,” the average foot soldier was in it for the money as the potential for martyrdom. On the battlefield, their superiors encouraged them to pillage the bodies of their enemies as well as the villages and cities they defended. As a result of this practice, those who survived the wars returned home richer than they had left.

Soon enough, merchants started taking part in the crusades as well. It was none other than the city of Venice, for instance, that lay siege to the affluent Lebanese city of Tyre and used its plundered riches to establish their now-infamous Mediterranean trading network. Years later, during the Fourth Crusade in Egypt, Venetian businessmen invested their newly gained wealth in a massive fleet that sailed out to conquer the even wealthier city of Alexandria.

Few organizations profited off the crusades quite like the Knights Templar, though. Conceived as an order of warrior monks living austere lifestyles defined by personal sacrifices made to the defense of the Holy Land, it did not take long before the Templars — benefitting off numerous tax exemptions and donations from kings, queens, and popes — became known as some of the richest and most influential people in all of Europe.

The end of the Templars

In a way, these benefits also brought about their downfall. The Temple Church started to crumble in 1244, the year Jerusalem was conquered by Khwarazmian mercenary armies from northern Iraq. Now that the Holy Land was no longer under European control, European pilgrims stopped making pilgrimages. Without pilgrimages, there was no reason for them to place their savings with the Temple Church, causing its funds to gradually deplete.

The Knights Templar held on for a few more decades after this point. Though they had lost a large portion of their clientele, their financial services remained available for wealthy citizens and members of the European nobility. That was until 1307, when King Phillip IV of France, knee-deep in debt to the order, started arresting, torturing, and burning Templars in France until his witch hunt convinced Pope Clement V to break them apart in 1312.

But while the Templars themselves are no longer around today, the legacy of the warrior monks lives on in the unlikeliest of places: in the records of Europe’s accountants, judicious administrators, and bankers.