Neanderthals: More knowable now than ever

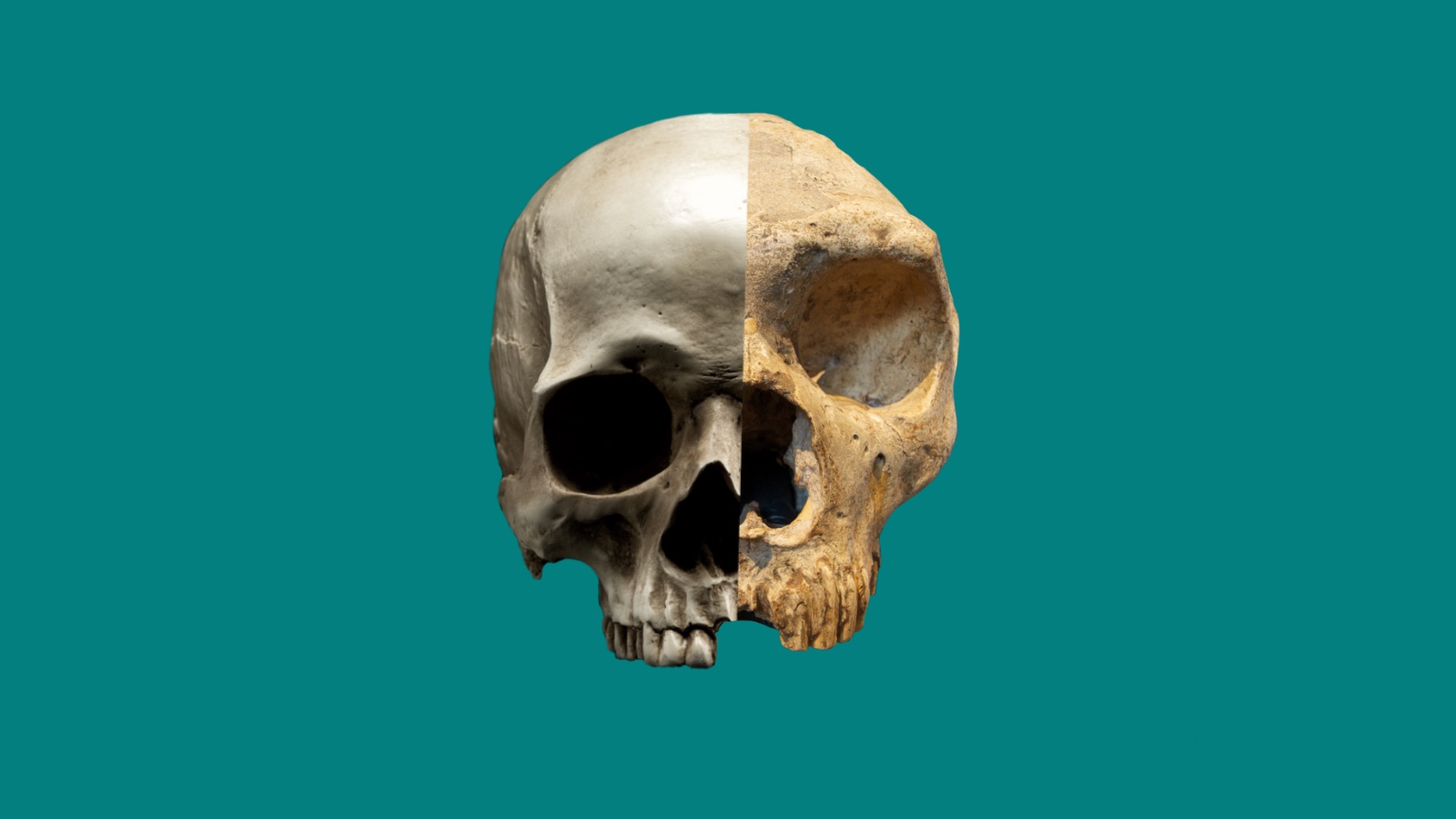

Neanderthals are Homo sapiens’s closest-known relative, and today we know we rubbed shoulders with them for thousands of years, up until the very end of their long reign some 40,000 years ago. Most researchers see no reason to believe our two species didn’t get along with each other back then, yet we haven’t been very kind to Neanderthals since their remains were first unearthed in the 19th century, often characterizing them as lumbering dimwits or worse. Even today, their name is sometimes hurled at misbehaving members of our own species, though there is no evidence they engaged in any kind of prehistoric hooliganism.

Well, with one exception, perhaps: What they did in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France would certainly be frowned upon today. Hundreds of intentionally broken stalagmites were found there, arranged into two large, ellipsoid structures and several smaller stacks, during a time when — as researchers confirmed in 2016 — only Neanderthals were roaming Europe. No one knows what these structures were for, but they suggest a tendency toward creativity and perhaps even symbolism.

No other structures of this kind have so far been discovered. But there have been many other hints that Neanderthal minds were occupied with things many researchers did not expect, says archaeologist April Nowell of the University of Victoria in Canada. The author of a 2021 book, Growing Up in the Ice Age, Nowell outlines the most exciting new discoveries in a 2023 article, “Rethinking Neandertals,” in the Annual Review of Anthropology.

“In the past 10 years, things have changed quite dramatically,” she says. “I never thought we’d have the wide range of information about their lives that we do now.” In addition to many new fossil discoveries, new methods for analyzing ancient biological molecules have allowed researchers to examine ancient DNA and proteins that they didn’t even know still persisted.

Most remarkably, researchers have spelled out the entire Neanderthal genome for multiple individuals, offering new insights into their biology, as well as our own — there is no longer any doubt that human beings and Neanderthals interbred. “Neanderthals are partly our ancestors, even if we didn’t evolve from them,” says paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London.

In addition, the many freshly unearthed or newly analyzed artifacts, some now confidently assigned to Neanderthals thanks to improved methods for dating archaeological finds, make for quite a collection. “If you’d have asked me 20 years ago, I would have said there was quite a big gap in behavior, and Neanderthals would have lacked many of the complex behaviors we find in Homo sapiens,” Stringer says. “Now that gap has narrowed considerably.”

Here’s some of what we have gleaned from what our close relatives left behind when they roamed the Earth between 400,000 and 40,000 years ago, across most of Eurasia.

Arts and crafts

Some of the Neanderthal artifacts discovered were very practical in nature. Bits of twisted wood fiber attached to a modified stone flake found in France in 2017 suggest that at least some Neanderthals knew how to make rope, for example, which may have opened the door to fashioning other objects like clothes, bags, nets and mats. There also is evidence that Neanderthals were heating birch bark to make adhesives — no mean feat. “A few researchers have recently tried to do the same in similar circumstances,” says Nowell, “and it’s a lot harder than most people thought.”

Beyond daily chores, Neanderthals evidently liked to adorn themselves. We now know they were using colorful pigments like red ochre as far back as 200,000 to 250,000 years ago, maybe not just on objects, but also on their own bodies — and they may have sometimes imported the substance from tens of kilometers away. Excavations have also revealed perforated and sometimes painted shells that were likely strung together and worn. A creative Neanderthal in Croatia made a necklace or other adornment out of white-tailed eagle talons, and elsewhere, tool marks found on bird bones suggest that feathers were also popular.

What about the famous cave art found in many sites in Europe and elsewhere? Until recently, none of these were thought to be Neanderthal. But in 2018, a study in Science demonstrated that the painted lines and dots on the walls of a number of caves in Spain must have been made by Neanderthals, since they were dated to a period when no Homo sapiens were yet around. There also is evidence of engraving — “hashtags” carved into a cave wall in Gibraltar, as well as on a pebble, a flint flake and a giant deer’s toe bone.

There are no indications yet that Neanderthals created any recognizable depictions of, for example, animals or people, says Nowell. That may have been a Homo sapiens innovation. “There are so many of these little isolated examples of interesting things Neanderthals were doing, these sorts of pulses of symbolic behavior. But they don’t seem to last for long periods of time or lead to something else as they clearly have in Homo sapiens populations,” she says.

Growing up human

One explanation for the differences in artistic expression may be that Neanderthals just thought differently. Perhaps a member of our own species excitedly asking a Neanderthal why they drew or carved what they did would have received nothing but a shrug. It is, of course, very hard to reconstruct what differences there may have been in brain structure or cognition, but Nowell is intrigued by a number of recent studies in which human brain cells were engineered to contain Neanderthal versions of some key brain development genes.

When grown in dishes in the lab, clusters of cells engineered to have one of these Neanderthal gene variants developed into minute brain-like structures that had a more popcorn-like shape than Homo sapiens brain cells do, while those with sapiens genes were more spherical. In another study of a different brain development gene, the sapiens mini-brains formed more neurons in the same time period than mini-brains containing the Neanderthal version.

These findings certainly suggest that the genetic differences between our species affect the structure of our brains. Still, it’s hard to know what these differences mean, Stringer says, or even if those gene variants are truly Neanderthal. Studying a more genetically diverse sample of Homo sapiens today might reveal more variation in our own species, and possibly more of an overlap with Neanderthals, he says.

“I do think there were cognitive differences between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens,” says Nowell. But, she adds, differences in demography may also have created more obstacles for Neanderthal culture to flourish. Neanderthals were thin on the ground — their global population may never have numbered more than 100,000 at any point in time. Maybe ideas didn’t spread because Neanderthals were too isolated, Nowell says, and then disappeared when local groups died out. Homo sapiens reached much higher densities and would have had much larger social networks.

New evidence indicates that Homo sapiens kids probably had longer childhoods, too. “We think Neanderthal girls probably reached sexual maturity earlier,” says Nowell: Studies of relatively commonly found fossils of Neanderthal children suggest that newborns had larger brains than sapiens newborns do and that they were growing faster.

“A longer childhood allows children more time to learn and experiment in relative safety,” Nowell says, giving sapiens children an edge.

She also notes that learning doesn’t just mean making new neurons and connections: It also involves pruning away connections that don’t prove useful. So if young sapiens brains were producing more neurons than Neanderthal brains, as the experiments suggest, and if our childhoods also lasted longer, “this might have supported more extensive learning,” she says, with more room for trial and error and making and breaking connections.

In(ter)breeding

New studies have recently provided some intriguing snapshots of Neanderthal family life. An analysis of DNA from remains of 11 individuals found in Chagyrskaya Cave in Siberia revealed that some were closely related and probably lived around the same time, says paleoanthropologist Bence Viola of the University of Toronto, who was involved in the excavation. “We’ve found a father-daughter pair, and a few individuals who either descended from the same mother or perhaps were mother, daughter and granddaughter.”

Genetic similarities were very high among all studied individuals, indicating that this was probably a very isolated population. “Men were even more highly related than women,” Viola adds, “suggesting it was probably more common for women to join a new group to find a mate.” This was probably the ancestral pattern in humans as well — it certainly still is in chimpanzees.

Though Neanderthals may have looked slightly odd to Homo sapiens, studies of ancient DNA show they did interbreed with our species. To Viola, that has important implications. “Homo sapiens clearly recognized Neanderthals as mating partners, which suggests they thought of them as humans — maybe ‘the weird guys living behind the mountains,’ but still, fellow humans,” he says. “More or less whenever both species extensively co-occurred, there has been genetic exchange.

An irresistible kiss

DNA may not have been the only thing our Homo sapiens ancestors exchanged with Neanderthals. Although our last common ancestor is thought to have lived at least 450,000 years ago, a 2017 study analyzing the DNA in calcified dental plaque on Neanderthal teeth showed that populations of a common microbe living in the mouths of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens genetically diverged at least 300,000 years later. This suggests that both species acquired the microbe from the same source around the same time — or somehow passed it to each other.

There are, of course, other possible explanations, such as shared food, says paleogeneticist Laura Weyrich of Penn State University, who led the study. “But the suggestion that it might have been a kiss proved irresistible to the media,” she says. “And you know, it might have been.”

That study also revealed other interesting aspects of Neanderthal behavior. The DNA analysis suggested that a Spanish Neanderthal with a dental abscess had likely been eating moldy plant matter covered in penicillin-producing fungus, as well as poplar bark containing pain-killing salicylic acid.

The study also cast significant doubt on the pervasive idea that all Neanderthals were staunch carnivores. While one Neanderthal from Spy Cave in Belgium had a fairly stereotypical diet of wild sheep and woolly rhino, the research revealed that this young adult also liked some mushrooms with their meal. “Neanderthals from El Sidrón Cave in Spain, on the other hand, didn’t seem to eat much meat at all,” says Weyrich. “Instead, it seems they mostly fed on mushrooms and, surprisingly, pine nuts.”

The lack of vegetables might be excusable — in a 2022 study, again based on the Neanderthal genome, an analysis of odor receptor genes found that Neanderthals would have been less sensitive to odors perceived as green, floral and spicy than we are. Yet at the site of Shanidar in current-day Iraq, researchers did find evidence that Neanderthals were cooking pulses such as lentils, while another recent study found grains of starch that suggest Neanderthals in Italy — of course — were making flour.

A Neanderthal nibbling pine nuts might sound like the pinnacle of flexibility, resilience and even good taste, but one gruesome detail needs to be mentioned here: Bones in El Sidrón also show signs of cannibalism. This may have had a cultural significance we are unaware of — rites involving cannibalism have existed in many cultures — but it doesn’t look as if the local population was thriving 50,000 years ago. (This is in stark contrast with a Neanderthal group in Germany 125,000 years ago that was apparently big enough to catch, butcher and eat elephants.)

Decline and persistence

Was cannibalism a sign of a species in decline, maybe even before Homo sapiens was making its first forays into Europe? It’s hard to say, but we have long wondered why Neanderthals went extinct and we didn’t. “Perhaps if Homo sapiens hadn’t been there,” Nowell says, “that niche would have stayed open for Neanderthals?”

There’s no evidence of any violence between Neanderthals and modern humans, Nowell adds; few researchers today seem to believe that Homo sapiens was hunting down Neanderthals. A higher infant mortality rate may be part of the explanation, Nowell says. “Even a small difference can lead to population decline across generations.”

But what was it about Neanderthals that put them at a disadvantage — if they were? Might it just have been bad luck? “I think, as Homo sapiens numbers grew after 45,000 years ago, Neanderthals were already in trouble,” says Stringer. “The environment in this period was fluctuating constantly from nearly as warm as the present day to freezing cold, sometimes within a few decades.” All the vegetation would be changing, animals were moving. “Maybe Homo sapiens was better able to cope with those changes, because they were networking more, helping each other out or exchanging cultural knowledge,” he says.

Even without direct confrontation, it’s conceivable that Neanderthals would have been compelled to give way to Homo sapiens and ended up on the margins of what used to be their favorite places to be. Nevertheless, says Nowell, Neanderthals may have played a role in our success. Homo sapiens might have brought new technologies, but it’s possible they also learned skills from Neanderthals, who had lived in Europe for millennia.

Eventually, the remaining Neanderthals, living in shrinking groups with few, if any, attractive mates, many of them close relatives, might simply have decided to join a Homo sapiens group, and could well have been welcomed there, says Viola. And because of our interbreeding, something of Neanderthals still survives in us.

“There’s more Neanderthal DNA in the billions of humans alive today than there ever was when they were still around,” Viola says. “In a way, Neanderthals are still here.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.