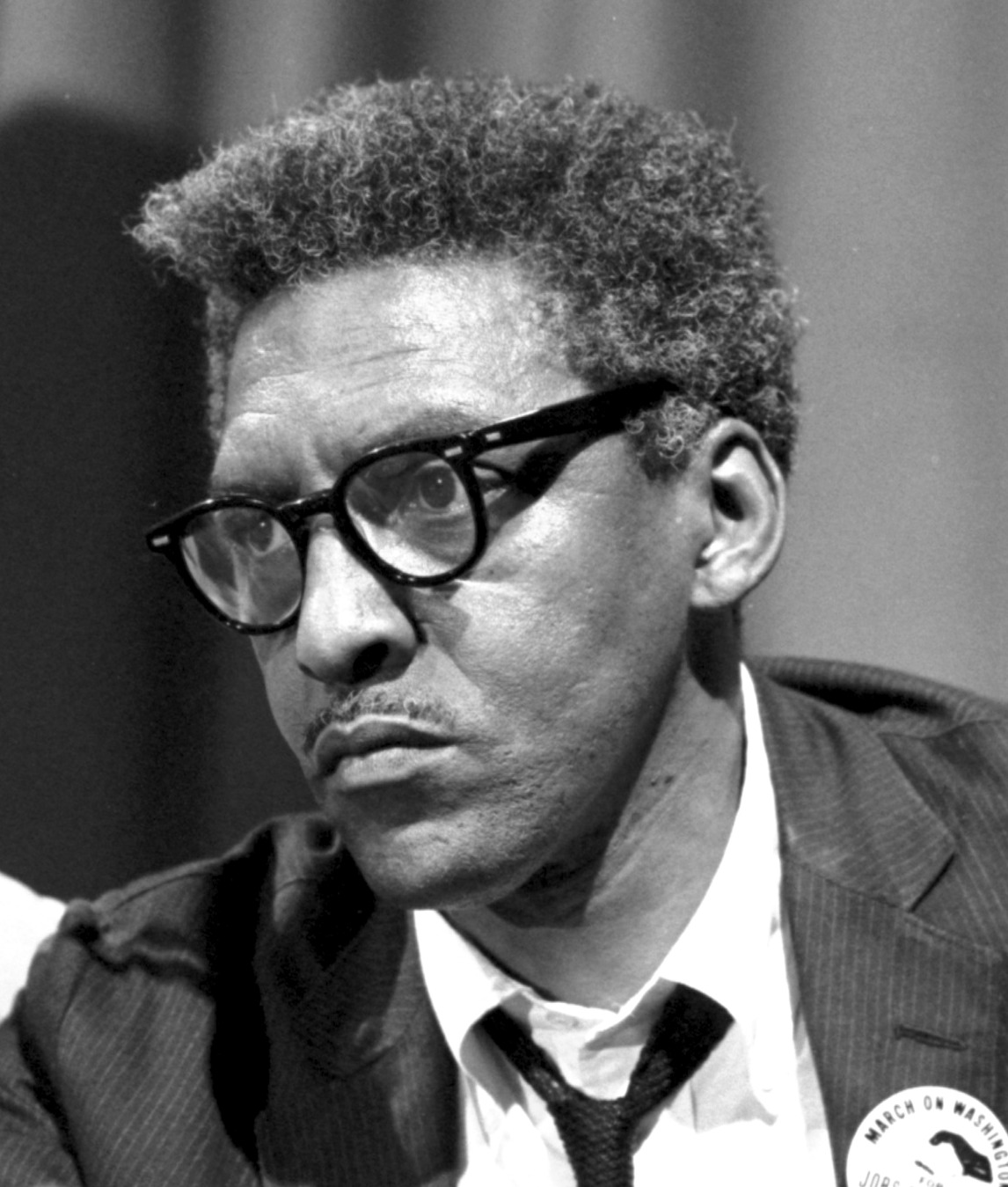

Why resolving “Rustin’s dilemma” helps strengthen any democratic coalition

- Bayard Rustin, known to some as “Mr. March on Washington,” organized the landmark historical event in 1963.

- Rustin recognized the dilemma of finding ways to unite diverse groups of people in the pursuit of shared goals despite their differences.

- Today, citizens in all democracies face the same challenges tackled by Rustin half a century ago.

Martin Luther King Jr. is the person most often associated with it, but Bayard Rustin, known to some as “Mr. March on Washington,” organized this landmark historical event in 1963. Rustin had many collective identities. He was black, gay, American, socialist, Quaker, pacifist, and he was also a political organizer.

Rustin’s influential social activist career spanned five decades, beginning in the 1930s as a college student at Wilberforce University. His first noteworthy organizing campaign, which focused on the economic dimension of racial oppression, came during 1941 when he was recruited by A. Philip Randolph to be the youth organizer for an earlier March on Washington movement that never occurred. The aim was to protest racial discrimination in the United States armed services and in employment. As part of a deal that Randolph struck with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who agreed to sign an Executive Order banning racial discrimination by federal agencies and all unions and companies engaged in defense work, the march was canceled — to the dismay of Rustin and the political rioters who subsequently burned down the movement’s Harlem, New York, Office.

Racial identity was activated to engage some people to support this march, as part of a shared project to end racial discrimination. But identity-driven collective action, as this case illustrates, also created difficulties as expectations diverged about what kind of action racial struggle demanded of blacks. A difference in perspective about whether to march or not is another instance of group heterogeneity. When building democratic political movements under an identity-like connection to address shared goals, we cannot ignore group differences in background, perspective, or empowerment. And it is important to note that such differences appear within and between groups. In addition to this lesson, as a political organizer, Rustin also learned that when our collective identities are scripted too tightly, which can happen by specifying their meaning in ways that some people find too restrictive, we can become boxed in.

Feeling as though one must act in a certain way because one is black, which is illustrative of being boxed in, can be an obstacle to collective action to achieve a shared goal, such as ending economic oppression. On some accounts of what it is to be black, says Rustin, “one is supposed to think black, dress black, eat black, and buy black.” And one is also supposed to associate exclusively with blacks (not whites, not Jews), especially when it comes to political struggle on behalf of the race. One complaint that Rustin had about more militant 1960s-era black activists such as Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown, to whom he attributes such views, is that by working with overly restrictive black identity scripts they ignored black heterogeneity, especially along class lines. Rustin believed that this was counterproductive to building a broad political movement to address economic problems in alliance with poor and working-class whites, class-conscious white liberals, and labor union activists, among others.

After black people used nonviolent protest to win civil rights, Rustin said: “What had previously been a movement seeking exclusively racial goals was now called upon to challenge the fundamental class nature of the economic structure.” And this new agenda required a different and broader alliance of political forces. Rustin was not naive; he understood that a “successful liberal political alliance is enormously difficult to build and, once pieced together, even more difficult to maintain, given the inevitable tensions, rivalries, and antagonisms of the various partners.” Still, he believed that forging such an alliance was necessary. Rustin insisted that realizing the goals of a new civil rights agenda meant that blacks needed allies who share “common problems and pursue common goals.” And the main challenge was picking the right allies on the basis of their “specific programs and proven willingness to cooperate with a political partner.”

Part of the sweeping economic reform that blacks could pursue with the right coalition allies included projects such as securing tax reform to redistribute wealth, federal jobs and basic income guarantees, and workforce development. Rustin faced the task of coordinating the collective pursuit of these and other projects in a manner that was attentive to intra- and intergroup heterogeneity. We call this Rustin’s dilemma. We face this dilemma with all kinds of projects, economic and otherwise.

[His] is not a story about heroes and villains. Rustin’s presumption that militant black activists calling for self-defense condoned the active use of violence in pursuing black rights was itself a case of boxing in with an overly restrictive script. Even he had to guard against this tendency. And it is not a story strictly about success — measured by either the outcome of political movements and coalitions or the uptake of civic responsibilities that it takes to form and sustain them. Rustin believed that successful protests should “produce a feeling of moving ahead” and should win new allies while forcing people to take notice of injustice in the struggle to leverage organized collective power for tangible change.

Rustin’s dilemma was an enduring feature of his life as an activist. It was also dynamic, as the differences in background, empowerment, and perspective he encountered with various coalition partners changed over time.

Rustin’s dilemma was an enduring feature of his life as an activist. It was also dynamic, as the differences in background, empowerment, and perspective he encountered with various coalition partners changed over time. Citizens in democracies continue to face their own versions of this dilemma today. As they seek to coordinate the pursuit of projects with diverse others, whether organizing a protest, an interfaith dialogue, or even a community garden, they run into the challenge of attending to group heterogeneity. And this is especially true in the face of tight scripts for racial, ethnic, partisan, and religious identities, among many others.

When facing Rustin’s dilemma, we can, of course, insist on the correctness of our own convictions. But given that heterogeneity persists, we face the further question of what to do next. Once Rustin and his intended coalition partners established their different conceptions of black identity, different policy priorities, or disagreement about protest tactics to adopt, they faced a further question: now what? Should they continue to communicate and negotiate? Should they establish a narrower set of projects on which to coordinate? Should they split up and pursue their projects separately? Identifying their different perspectives, backgrounds, and forms of empowerment was only the start of a longer process.

Alongside the challenge of heterogeneity, Rustin faced this “now what” question repeatedly over the course of his life. Citizens in democracies today also face this question. Taking up these responsibilities will lead us to use the right processes, and develop the right ethos, for holding ourselves and others accountable to heterogeneity as we answer the “now what” question [to] break free from, rather than propagate, tight identity scripts.