In the Soviet Union, murderers had an easier time than political dissenters

- Soviet law, like any other part of Soviet society, was rooted in the principles of Marxism-Leninism.

- As interpretations of these principles changed, so did the way in which the Soviet state treated its criminals.

- When studying criminal justice in the USSR, an important distinction must be made between political and non-political criminals.

When Andrei Chikatilo was taken to court for murdering 52 people, he refused to take any responsibility for what he had done. The murderer, who needed to be placed in an iron cage to protect him from the enraged families of his victims, believed that his crimes were caused not by his own free will, but forces beyond his control.

Chief among these was his admittedly traumatic upbringing. Chikatilo, one of the most infamous serial killers in the history of the Soviet Union, was born during the Holodomor: a man-made famine that took the lives of an estimated 3.5 million Ukrainian peasants. He grew up on a collective farm. As a child, Chikatilo frequently fainted from hunger, inviting bullies to pick on him.

Biology, Chikatilo argued, was a contributing factor as well. From childhood on, the serial killer had struggled with impotence. He was unable to maintain an erection during ordinary sexual contact, but instantly ejaculated when jumping his sister’s friend and wrestling her to the ground. Later, he discovered that he received even more sexual gratification from stabbing and torturing.

Chikatilo had been evaluated by several psychiatrists while he was held in custody. During the trial, his lawyer wanted these psychiatrists to take the stand so he could ask them whether his client’s troubled psyche cleared him of culpability. When this motion was denied, Chikatilo became unruly and incoherent — a possible attempt to fool the court into thinking he was, after all, insane.

The murderer said he was pregnant and lactating, and that he had gotten into a fight with the Assyrian mafia. According to Mikhail Krivich and Olgert Ol’Gin, authors of Comrade Chikatilo: The Psychopathology of Russia’s Notorious Serial Killer, claim that at one point Chikatilo pulled out his penis, saying, “Look at this useless thing. What do you think I could do with that?”

Whatever Chikatilo had been trying to do, it did not work. His trial, which became the first major news event following the fall of the Soviet Union, ended the way people had expected. The so-called “Ripper of Rostov” was sentenced to death. In February 1994, he was shot in the head and buried in an unmarked grave in the cemetery of his prison.

Criminal justice in post-revolutionary Russia

Had Chikatilo gone to trial when Vladimir Lenin was in charge, he might have met a very different fate. During this early period of Soviet history, the Communist Party was still figuring out how it could translate its idealist philosophy into a practical form of government, and Lenin — unlike his successor — was not the type to make concessions.

Initially, the Bolsheviks tried to organize their legal system according to the teachings of Karl Marx. Among hardline Marxists in Russia at the time, “guilt” and “punishment” were seen as instruments of bourgeois culture — tools that the country’s haves had previously used to keep the have-nots in their place.

Unwilling to adopt a legal terminology that originally belonged to their class-enemies, the revolutionaries opted to create their own language. “Guilt” vanished from the legal dictionary. Rather than punishments, people now spoke of “social defenses,” and crimes were rebranded as “socially dangerous acts” — actions which got in the way of the state achieving Socialism.

Early Soviet researchers made significant contributions to the discipline of criminology, especially with regards to juvenile delinquency. This was a pressing topic for them. Years of war, revolution, and civil war had taken their toll on the next generation of Russians. The economy collapsed and families were torn apart, pushing an ever-increasing amount of youngsters into criminality.

In 1918, the Communist Party sought to reverse this trend by creating a law that prevented delinquents aged 17 and 18 from being tried in court. Instead, their futures were determined by “Commissions for the affairs of juveniles,” consisting of judges, pedagogues, and physicians that formulated a response based not on the delinquent’s crime but level of “social neglect.”

“Under no circumstances,” Nathan Berman writes in an article for the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, “could the Commission commit juveniles to a penal institution, no matter how serious or felonious their offenses happen to be. These youthful offenders could be treated only along ‘medical-pedagogical’ lines.”

Murder under Stalin

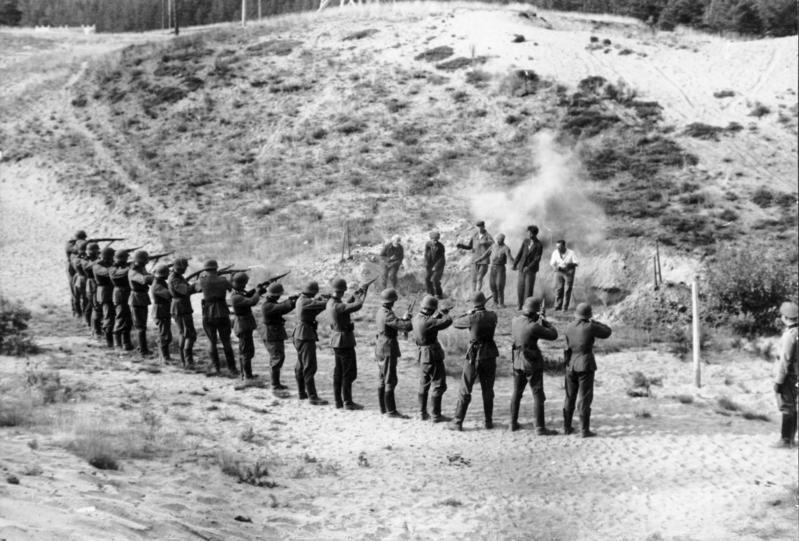

Revolutionary though this early approach to youth crime was, it did not last. In 1935, the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party issued a decree determining that minors from the age of 12 who are found guilty of theft, assaults, murder, or attempt at murder were “liable to all the grades of criminal penalty,” which included the death penalty.

The call to reinstate this penalty came not from Stalin himself but his closest associates. In the same year, Kliment Voroshilov, the People’s Commissar for Defense, had written Stalin a letter in which he argued capital punishment was the most effective way to combat the rising crime rates among Moscow’s disenfranchised youth.

One of the juvenile delinquents that was directly affected by this decree was the serial killer Vladimir Vinnichevsky. Had Vinnichevsky been tried a decade earlier, he might have been able to avoid the death sentence. Instead, the 17-year-old was charged with murdering eight people, for which he was executed and buried in an unmarked mass grave along the Moscow tract.

Vinnichevsky’s execution offers but one example of how the Soviet legal system had changed under Stalin. Where Lenin’s 1917 book The State and Revolution promised the government of the Soviet Union would “wither away” as Russia drew closer to achieving Socialism, Stalin in 1936 proclaimed that the USSR needed “the stability of laws now more than ever.”

This declaration was of a political rather than an ideological nature. After all, 1936 marked the start of Stalin’s Great Purge: a period in which the General Secretary relied on the power of the state to neutralize both the real and imagined threats that were facing his regime. Terror and law, which had previously been administered separately, suddenly became the responsibility of the same government agencies.

To justify the mounting number of arrests and executions, modifications were made to the Marxist-Leninist framework that had underpinned all aspects of Soviet governance. Where the first generation of Bolsheviks had been staunchly deterministic, theoreticians under Stalin reintroduced the notion that individual people actually possessed a considerable degree of agency and autonomy.

Political versus non-political crimes

The effect of these modifications was twofold. On the one hand, they helped cement Stalin as someone who was single-handedly saving the Soviet Union from collapsing in on itself. On the other, they provided lawmakers with an ideological basis to hold criminals accountable for their actions, which had previously been blamed on the environment.

Russia scholars studying this period maintain the Purge had less of a long-term impact on the integrity of the USSR’s legal system than one might expect, a claim that seems to be corroborated by the firsthand accounts of several Soviet lawyers who wrote about their experience in the field after the Communist Party was disbanded in 1991.

In her book, Final Judgment: My Life as a Soviet Defense Attorney, Dina Kaminskaya states that the majority of trials of non-political crimes were conducted fairly and professionally. Lawyers, judges, and police investigators worked together to ensure that each case was thoroughly investigated, and that the sentence was appropriate to the gravity of the crime.

Political criminals were not given the same treatment, mainly because the Soviet Union considered them to be more dangerous to the regime than non-political ones. A mass-murderer like Vinnichevsky might ruin the lives of a few hundred people, their reasoning followed, but antisocial individuals such as him would never be swept up in rebellions that threatened the Communist Party.

Whether Stalin’s approach to criminal justice was more or less effective than Lenin’s is hard to say. Government records of criminal justice were issued consistently and prodigiously during the 1920s, but became scarcer after the Great Purge. What statistics the government did release were often obtuse, and seldom trustworthy.

What is for certain is that the study of criminal justice in the Soviet Union is largely contingent on the study of Marxism-Leninism because this political ideology not only shaped the way in which criminals like Chikatilo contextualized their own actions, but also how the state determined the degree to which they could subsequently be held accountability for those actions.