Strauss-Howe generational theory: Is revolution coming to America?

- Every generation is influenced by unique cultural events.

- The resulting ideological differences lead to recurring crises, conflicts, and reconstructions.

- It’s a compelling and marketable idea, but not without its flaws.

Ever heard of the phrase, “Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times?” Chances are you have. This catchy warning about the cyclical nature of history can be found in the most unlikely of places: internet memes, inspirational posters, and even embroidered onto sets of Etsy cushions.

Although generally attributed to author G. Michael Hopf’s post-apocalyptic novel Those Who Remain, the underlying idea probably originated with a 1991 book called Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. Written by William Strauss, a playwright, and Neil Howe, a historian and senior associate for the Global Aging Initiative’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, Generations argues the development of human civilization is heavily affected by and even mirrors the transition between different generations of human beings. According to the so-called Strauss-Howe hypothesis, as their train of thought is now known, history can be roughly divided into periods of 80 to 100 years. In each period, four generations compete for power, resulting in a crisis moment followed by radical social and political reconstruction. In the case of the U.S., such crisis points include the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the Second World War.

Aside from having at least some precedent in the field of sociology, the Strauss-Howe hypothesis or simply generational theory also appeals to common sense. Each generation is shaped by unique events and challenges, so it follows that their values would influence the events of their day. At the same time, the theory has drawn its fair share of criticism, with many claiming it’s more science fiction than science.

Weight of ancestors

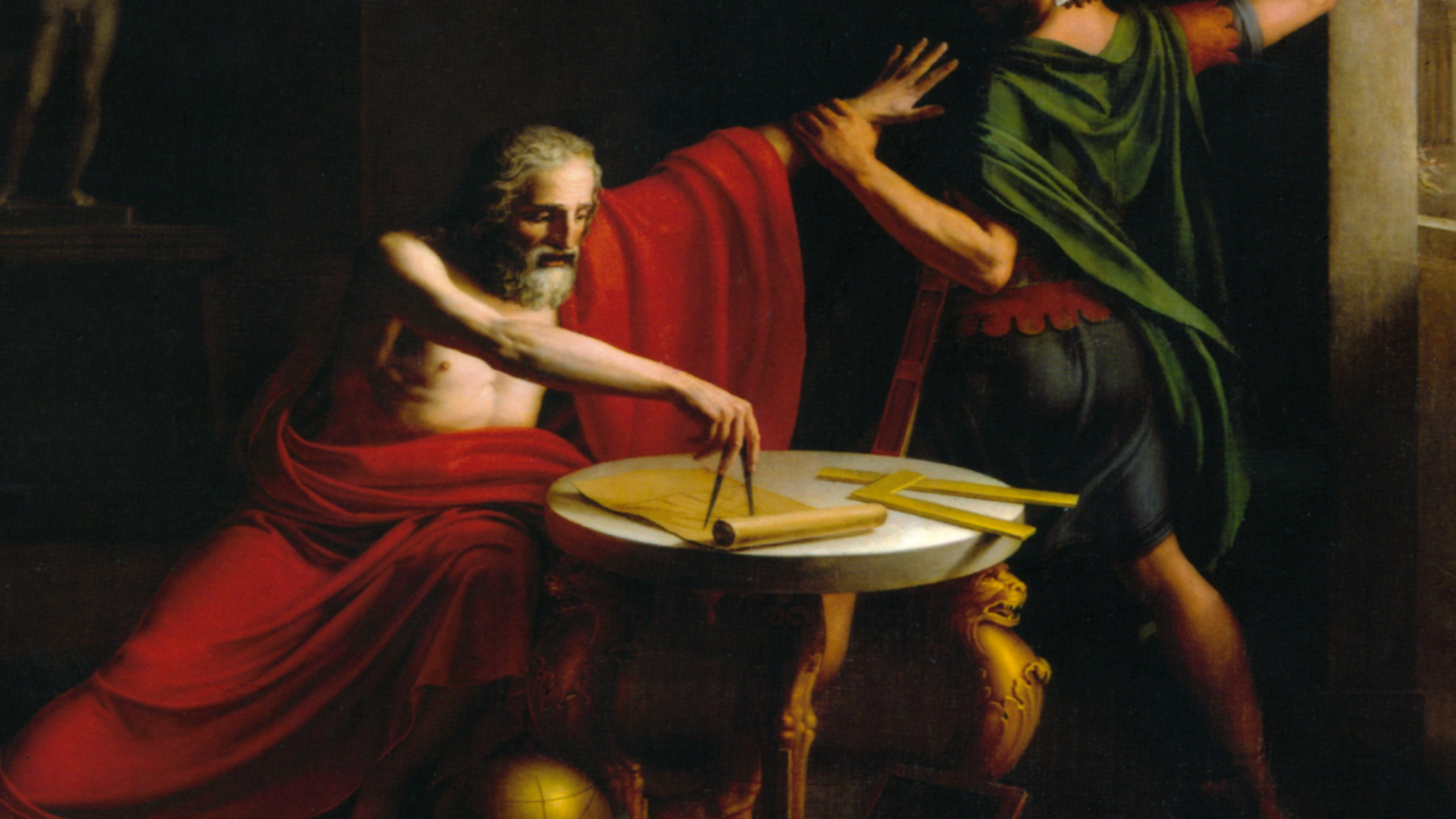

Although the topic has only attracted attention from scholars in recent decades, people have been talking about the importance of generations since the days of ancient Greece. When, in Homer’s Iliad, the Greek warrior Diomedes asks his Trojan foe Glaucus who he is, the latter doesn’t mention his age, sex, profession, or place of origin — instead, he gives a comprehensive overview of his entire family tree.

“Greathearted son of Tydeus,” he tells the Greek:

“Why do you question my lineage / As is the generation of leaves, so too of men: At one time the wind shakes the leaves to the ground, but then the flourishing woods / Gives birth, and the season of spring comes into existence; So it is of the generations of men, which alternately come forth and pass away.”

Compared to the Christian Europe of medieval times, which emphasized the individual’s responsibility to live a morally upright life and enter heaven, the Homeric Greeks saw themselves first and foremost as the product of their forefathers, the fruits of their ancestry evident in their very person.

Even if they don’t accept every tenant of the Strauss-Howe hypothesis, many sociologists accept generation as one of the key factors explaining sociocultural change. In doing so, they follow the example of Karl Mannheim, a Hungarian scholar who argued generations are defined not by birthdays, but shared experiences that influence one’s values. Mannheim also argued that, for a generation to manifest, its members needed to actively acknowledge the experiences that influenced them — through books, news reporting, and other means of cultural production. It’s the same with self-fulfilling prophecies, really; only when a group recognizes itself as a group does it begin to act as one.

Of course, it’s one thing to say generations are shaped by history, and another to say they shape history in turn. And while academics are happy to admit that first bit, they continue to have strong doubts about the second.

Problems with the Strauss-Howe hypothesis

To some, generational theory is no more than pseudo-historicism blown out of proportion by the media, no more reliable than, say, the Phantom Time hypothesis, which makes the outrageous claim that Holy Roman Emperor Otto III added three centuries to the Gregorian calendar to make his own reign coincide with the year 1000 AD. (That’s another story, though.)

One of the biggest problems with the Strauss-Howe hypothesis is that generations are a subjective measurement, one that requires researchers to make gross generalizations about the individuals they study. It also operates on the questionable assumption, as the Forbes journalist Jessica Kriegel puts it, “that cultural events determine personality more than life experience and circumstance,” a claim many sociologists readily debate.

Strauss and Howe’s notably unacademic backgrounds should also ring some alarm bells. Bestselling writers first and scholars second, the duo has arguably masked their lack of expertise behind language compelling and marketable enough to turn Generations into a kind of media empire: the ninth book in the series, The Fourth Turning Is Here: What the Seasons of History Tell Us about How and When This Crisis Will End, was released last year.

There are other problems. Generational theory holds that people’s worldview and behavior — decided by the era in which they were born — remain static throughout their lives. This is, of course, not the case, with numerous studies showing that things like religion, political beliefs, sexual preference, and even personality can change over a person’s lifetime.

Furthermore, Strauss and Howe’s aspiration to apply their hypothesis on a global scale ignores the undeniable fact that generations — if there even is such a thing as a generation — form at different times in different countries and cultures, making it impossible to summarize world history by lining up randomly selected grandsons, sons, fathers, and grandfathers.

The Fourth Turning

The terms of the Strauss-Howe hypothesis are vague enough to the point that anyone can cherrypick evidence and create a persuasive narrative around them. That said, Strauss and Howe’s is pretty persuasive. Their assessment of the four generations that make up American society (Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, and the Baby Boomers), for instance, goes as follows:

The Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, grew up in a time of nearly uninterrupted economic growth, making them both optimistic and idealistic. Gen X (1965-1980), raised during the hardships of the oil crisis, turned against the capitalist-consumerist culture their parents embraced, forming countercultures. Gen Y (that is, Millennials, 1982-1994) was born during another period of financial security, one that coincided with the advent of the digital world. The comfortable, sheltered environment in which they grew up, Howe says in The Fourth Turning — an environment of Apple computers, Power Rangers cartoons, and a collapsing Soviet hegemony — made them self-assured, attention-seeking, and perfectionistic, qualities that, in the far less secure world we call home today, manifest as stress, burnout, and generalized anxiety disorder. According to Howe, Millennials will soon upend the conservative order put in place by the Baby Boomers, transforming the country in much the same way as the Revolutionary War or Civil War have done before.

Time will tell if Strauss and Howe are right.