Americans don’t understand their government. They’re paying the price.

- Surveys show many Americans lack a basic understanding of their government, its history, and how it works.

- One reason is that civics has been deprioritized in education in favor of STEM and language arts.

- When political know-how is low among a populace, misinformation spreads easily, and citizens don’t have the confidence to engage with the system.

Americans need to talk more about politics. That may seem a ridiculous claim to anyone who has spent any time scrolling through social media, listening to vox-pop reporting, or telling their conspiracy-loving uncle that no, they don’t want to read his literature concerning all the problems with you-know-what (because of you-know-who).

Such interactions rarely qualify as talking, though. Arguing, scolding, lecturing, shouting, moralizing, soap-boxing, and grandstanding, sure. An honest-to-goodness conversation? Not so much. Americans have ingrained in themselves the tendency to either treat politics as a winner-take-all spectator’s sport or avoid the discussion altogether out of a sense of wary decorum.

“We are unable to have conversations about these things because we often feel like [we] don’t know enough. We lack the confidence to go into these conversations,” Lindsey Cormack, an associate professor of political science at the Stevens Institute of Technology, says.

And Americans may be right to lack this self-assuredness. Research shows that political knowledge regarding basic government principles and operations is surprisingly low in the United States. According to an Annenberg Public Policy Center survey, one-third of Americans polled couldn’t name all three branches of their government, and two-thirds couldn’t name three of the five rights enshrined in the First Amendment. Similarly, a Pew Research Center survey found that more than half of respondents didn’t know the length of a senator’s term in office or who selected the president if the Electoral College was tied.

It’s also worth noting that these surveys looked explicitly at the federal government, the political realm Americans are most acquainted with. As Cormack points out in her book, How to Raise a Citizen, the results are even more disheartening when it comes to state and local politics.

By now, American readers may be thinking, “Well, yeah. Those fools on the other side of the aisle are dragging the average down. It’s part of why I’m so frustrated with them!” If so, then prepare for the cold water. Regarding civic and political knowledge, Pew’s data found “virtually no partisan difference.” Republicans and Democrats are equally well-informed — or uninformed, depending on your preferred framing.

As with any social trend, there is no easy fix to America’s political woes, but a necessary step in solving them is the ability to have constructive conversations based on shared knowledge. “I don’t know anything that gets better by people not being willing to talk about it,” Cormack says.

Big Think recently spoke with Cormack to discuss why political knowledge is scarce in America, the social costs paid for this unawareness, and how Americans can renew our confidence in the system and each other.

Teacher, don’t leave them kids alone

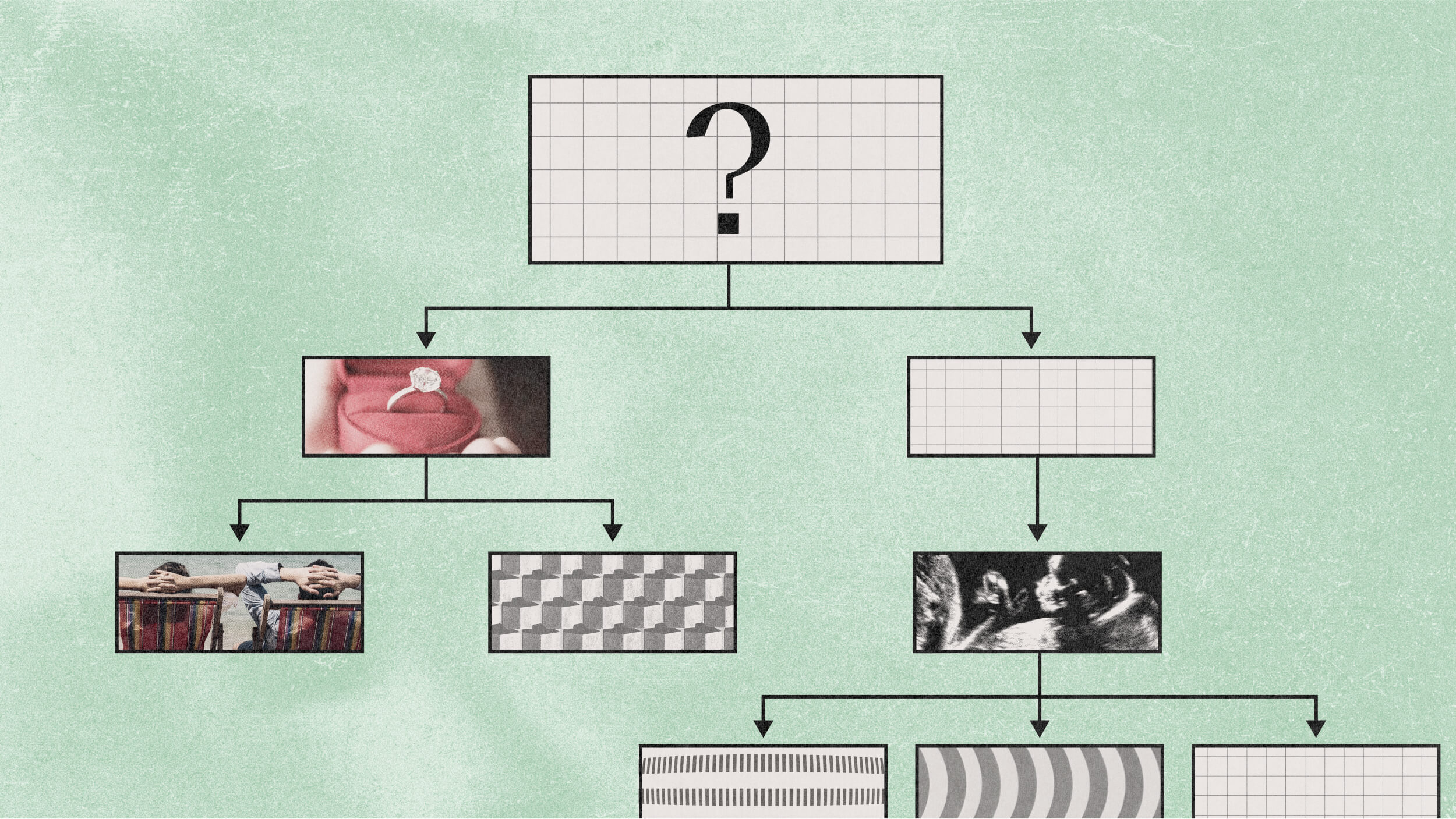

One reason Americans lack robust knowledge, confidence, or conversational know-how in politics is simply that they weren’t taught much about how their government works. Most parents rely on schools to teach their children civics; meanwhile, schools tend to give the subject short shrift because social incentives overwhelmingly favor other subjects.

Since the Cold War, the United States has prioritized STEM in a bid to stay globally competitive, and this fixation has led educational standards and funding to focus heavily on math and language arts. Today, Cormack notes, civics receives roughly 5¢ of funding for every $50 that goes to STEM. Additionally, many districts evaluate teachers and schools based on test scores, resulting in curricula that prioritize test preparation in these subjects.

That’s not to say civics has been abandoned. Many states teach the subject at some level of schooling. However, few states assess civics as a standalone subject, and graduation requirements are all over the place. Some states require a year of civics education, some only a semester, and some have no requirement at all.

“It’s really a patchwork,” Cormack says. “You can find out what states require, but when you talk to teachers, they’ll [tell you] that school boards don’t enforce it or they couldn’t find someone to teach it. So, it’s very hard to assess what kids are actually learning.”

This patchwork system makes it difficult to say what Americans, broadly speaking, do or don’t learn about civics. The best yardstick is the Nation’s Report Card, a survey conducted by the National Center for Educational Statistics. Since 1998, the survey has tested students’ civics knowledge, and the results haven’t been rosy.

Of eighth graders tested, the vast majority performed at a basic or below basic level — that is, they can define some aspects of the government or Constitution but cannot discuss how citizens can interact within the political process. Only about 23% of students in any given year perform at proficiency or above.

Another consequence of this nominal focus is that civics ends up being taught differently than other subjects. Math and English start with foundational concepts that build necessary skills early before layering on more complex concepts and theories. Conversely, civics is often taught as a checklist of must-memorize facts that don’t build into valuable skills. The short time frame is partly to blame, but so is a social climate that makes teachers and districts fearful that going beyond the “most anodyne” of trivia risks a social media firestorm.

The result? “It turns kids into spectators of history rather than participants,” Cormack says.

That’s precisely what the data shows. According to the Harvard Youth Poll, a national survey of 18-to-29-year-olds, “most young Americans do not believe that their high school education taught and prepared them to understand practical aspects of voting and civic education.” Fewer than half of those surveyed said their education taught them how to register to vote, research candidates and ballot issues, or request and submit a ballot. And voting is the democratic door that, in Cormack’s words, “allows a person entry into every other part of politics.”

“When people know about a system and how to participate in it, participation goes up,” Cormack writes in her book.

And, of course, people who aren’t taught about government, lawmaking, or civic engagement — in school or at home — will often find it challenging to make up for these scholastic shortcomings when they become parents themselves.

Not all politics is local (but a lot is)

The costs Americans pay for this civic deficit are more than low voter turnout — though that is important and lackluster compared to other democracies. Cormack worries that misinformation is easier to spread among people who don’t have the prerequisite knowledge to question it. That information can further be used to stoke unnecessary fears and anxieties regarding what the government is doing or may be capable of.

“If you read a headline that you can’t make sense of, it has the potential to be more fearful if you don’t have a rooted understanding of the government [and its] structure,” Cormack says. “[People can] reduce the mental temperature on things that feel scary when they’re more rooted and understand what’s really happening.”

She points to the January 6th U.S. Capitol Riot as a recent example of what happens when fear and misinformation push people to a breaking point. “I don’t think anyone who stormed the Capitol on that day thought they wouldn’t get their way. An idea was able to flourish because they didn’t have an understanding of what was actually going to happen or what our laws say.” And while political violence is on the extreme side of things, Cormack adds, “We’ve certainly seen it, so it is a problem.”

Another associated cost is American citizens who lack the ability and confidence to engage with the political system to improve their and their neighbors’ lives. There are many potential ways for this cost to play out — or, rather, not play out — but an important one is America’s habit of neglecting state and local politics.

“We understand the federal level of government best. If you ask people where their state politics happens, they probably won’t be able to tell you,” Cormack notes.

That’s unfortunate, but as Cormack points out, state and local politics is where many decisions that affect the quality of people’s daily lives are made. These include policies surrounding healthcare, gun control, marijuana policies, road repairs, and, of course, education.

That’s not to say the federal government has no say over such matters. It does. But often, whether the rubber meets a well-paved road or a pothole is decided at a political body more local than Washington, D.C. This proximity to representative decision-makers means citizens have much more influence than they think. Citizens need to know how to engage them.

“We think of ourselves as on the ship of politics,” Cormack says. “We’re the passengers wondering where this is going. But we’re really the crew. We just don’t realize it. We’re the ones who are steering the ship, and when we don’t take on that responsibility, we find ourselves in places we don’t really want to be.”

Steering the ship of state

What can Americans do in the face of such obstacles? One thing is to have more constructive conversations. Be willing to talk. Share something with others. Learn from the experts who have spent time understanding the country’s byzantine federal system. Again, if you’ve been on social media, read the news, or spent a holiday with your conspiracy-loving uncle, you’ll recognize that’s easier said than done. Thankfully, Cormack has some advice to help her fellow Americans out.

First, if you live in America or any modern democracy, appreciate that fact. When the U.S. Constitution was signed in 1787, the vast majority of the world’s population lived in closed autocratic societies. Even today, billions still live under such systems. That anyone should thrive in a country that affords them democratic rights isn’t a miracle but a hard-won patrimony.

“The fact that we live in a democracy is one of the most beautiful, underutilized opportunities that we have,” Cormack says, adding:

“How lucky are we to be living in a system that allows us to hop in and say, ‘I have to do hard things. I care about where I live. I care about my life. I care about the lives around me and the lives that will come after me. Let’s make this better. We only get to be here once. Why not expend a little effort and do something?”

Next, Cormack recommends figuring out where your input may make things better. That may be a simple fix, such as filling in a pothole or fixing a streetlight. It may be a more complex project, like adding bike lanes to a busy road or turning a brownfield site into a local park.

Once you figure out where you want to make a change, start with a person, not a process. Schedule an appointment with your mayor or a staffer. Introduce yourself to your representative councilor after the next meeting. Join a local committee interested in similar changes. By engaging with people already in the process, Cormack points out, you learn from their experience, benefit from their advice, and shortcut your own efforts. And with something like a pothole, making the right person aware of the problem is often enough to fix it.

“You have to link [people] with the players instead of teaching it to them as some theoretical system that governs us in the abstract,” Cormack says. “You have to show them that [government] is people, and you can talk to people. You can influence people. It doesn’t always work out, but you can try.”

If you’re a parent, you’ll need to learn what your children are taught about civics and when. You may luck out and discover your local district sports a robust civics unit, but even then, you’ll need to help your child figure stuff out. Why should civics be any different than the Pythagorean theorem or noun-verb agreement?

At a minimum, Cormack suggests children know how to register to vote and cast a ballot before leaving home. They should also understand how federalism works, have read the Constitution through at least once, and have practiced engaging in difficult yet constructive conversations. As a bonus, when teaching children these things, parents reinforce their own knowledge.

By the people, for the people

You may not have heard of Danielle Avisar, but she is an example of what happens when people in a democracy recognize that they are steering the ship. In 2022, she was riding a New York City bus with her young children when the bus driver informed her she would have to fold up the stroller or get off the bus. Avisar was taken aback. How does someone fold up a stroller while juggling two young children and manage the feat safely in a soon-to-be-moving vehicle?

Deciding the status quo wasn’t acceptable, she and a group of like-minded parents got together. They called on New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) to change the rules. In response, the MTA launched a pilot program to allow open strollers in specific areas of the bus.

“I’m in awe of people like her,” Cormack says. “A lot of people were mad about [the stroller rule], but no one had the wherewithal to just say, “Let’s figure out how we can change it.’ She did. People like her are civic role models.”

Did everyone celebrate the change? Of course not. It’s a democracy. Some argued the strollers would be obstacles on the bus or cause disputes over space — reasons the original rule was put in place. But MTA launched a second phase to retrofit buses across all five boroughs to include designated spaces for strollers, keeping them safer and out of the aisles.

Will the retrofits be perfect? Probably not. As economists are always eager to remind us, there are no solutions, only trade-offs. But the true value of modern democracies isn’t that they’re perfect; it’s that they allow their citizens to have a say on what those trade-offs should be because their citizens are a crucial part of that government. But that only works if citizens understand their government, recognize the role they have to play, and have the confidence to do it.

“When we are unwilling to do those things, we get outcomes that many people probably didn’t want because they’re unwilling to chime in and do something like that,” Cormack says.