We are all conspiracy theorists

Credit: YURI KADOBNOV via Getty Images

- Conspiracy theories exist on a spectrum, from plausible and mainstream to fringe and unpopular.

- It’s very rare to find someone who only believes in one conspiracy theory. They generally believe in every conspiracy theory that’s less extreme than their favorite one.

- To some extent, we are all conspiracy theorists.

The following is an excerpt from the book Escaping the Rabbit Hole by Mick West. It is reprinted with permission from the author.

If you want to understand how people fall for conspiracy theories, and if you want to help them, then you have to understand the conspiracy universe. More specifically, you need to know where their favorite theories are on the broader spectrum of conspiracies.

What type of person falls for conspiracy theories? What type of person would think that the World Trade Center was a controlled demolition, or that planes are secretly spraying chemicals to modify the climate, or that nobody died at Sandy Hook, or that the Earth is flat? Are these people crazy? Are they just incredibly gullible? Are they young and impressionable? No, in fact the range of people who believe in conspiracy theories is simply a random slice of the general population.

There’s a conspiracy theory for everyone, and hence very few people are immune.

Many dismiss conspiracy theorists as a bunch of crazy people, or a bunch of stupid people, or a bunch of crazy stupid people. Yet in many ways the belief in a conspiracy theory is as American as apple pie, and like apple pie it comes in all kinds of varieties, and all kinds of normal people like to consume it.

My neighbor down the road is a conspiracy theorist. Yet he’s also an engineer, retired after a successful career. I’ve had dinner at his house, and yet he’s a believer in chemtrails, and I’m a chemtrail debunker. It’s odd; he even told me after a few glasses of wine that he thinks I’m being paid to debunk chemtrails. He thought this because he googled my name and found some pages that said I was a paid shill. Since he’s a conspiracy theorist he tends to trust conspiracy sources more than mainstream sources, so he went with that.

Why do people believe in conspiracy theories? | Michio Kaku, Bill Nye & more | Big Thinkwww.youtube.comI’ve met all kinds of conspiracy theorists. At a chemtrails convention I attended there was pretty much the full spectrum. There were sensible and intelligent older people who had discovered their conspiracy anything from a few months ago to several decades ago. There were highly eccentric people of all ages, including one old gentleman with a pyramid attached to his bike. There were people who channeled aliens, and there were people who were angry that the alien-channeling people were allowed in. There were young people itching for a revolution. There were well-read intellectuals who thought there was a subtle system of persuasion going on in the evening news, and there were people who genuinely thought they were living in a computer simulation.

There’s such a wide spectrum of people who believe in conspiracy theories because the spectrum of conspiracy theories itself is very wide. There’s a conspiracy theory for everyone, and hence very few people are immune.

The mainstream and the fringe

One unfortunate problem with the term “conspiracy theory” is that it paints with a broad brush. It’s tempting to simply divide people up into “conspiracy theorists” and “regular people” — to have tinfoil-hat-wearing paranoids on one side and sensible folk on the other. But the reality is that we are all conspiracy theorists, one way or another. We all know that conspiracies exist; we all suspect people in power of being involved in many kinds of conspiracies, even if it’s only something as banal as accepting campaign contributions to vote a certain way on certain types of legislation.

It’s also tempting to simply label conspiracy theories as either “mainstream” or “fringe.” Journalist Paul Musgrave referenced this dichotomy when he wrote in the Washington Post:

Less than two months into the administration, the danger is no longer that Trump will make conspiracy thinking mainstream. That has already come to pass.

Musgrave obviously does not mean that shape-shifting lizard overlords have become mainstream. Nor does he mean that flat Earth, chemtrails, or even 9/11 truth are mainstream. What he’s really talking about is a fairly small shift in a dividing line on the conspiracy spectrum. Most fringe conspiracy theories remain fringe, most mainstream theories remain mainstream. But, Musgrave argues, there’s been a shift that’s allowed the bottom part of the fringe to enter into the mainstream. Obama being a Kenyan was thought by many to be a silly conspiracy theory, something on the fringe. But if the president of the United States (Trump) keeps bringing it up, then it moves more towards the mainstream.

Both conspiracy theories and conspiracy theorists exist on a spectrum. If we are to communicate effectively with a conspiracy-minded friend we need to get some perspective on the full range of that spectrum, and where our friend’s personal blend of theories fit into it.

It’s very rare to find someone who only believes in one conspiracy theory. They generally believe in every conspiracy theory that’s less extreme than their favorite one.

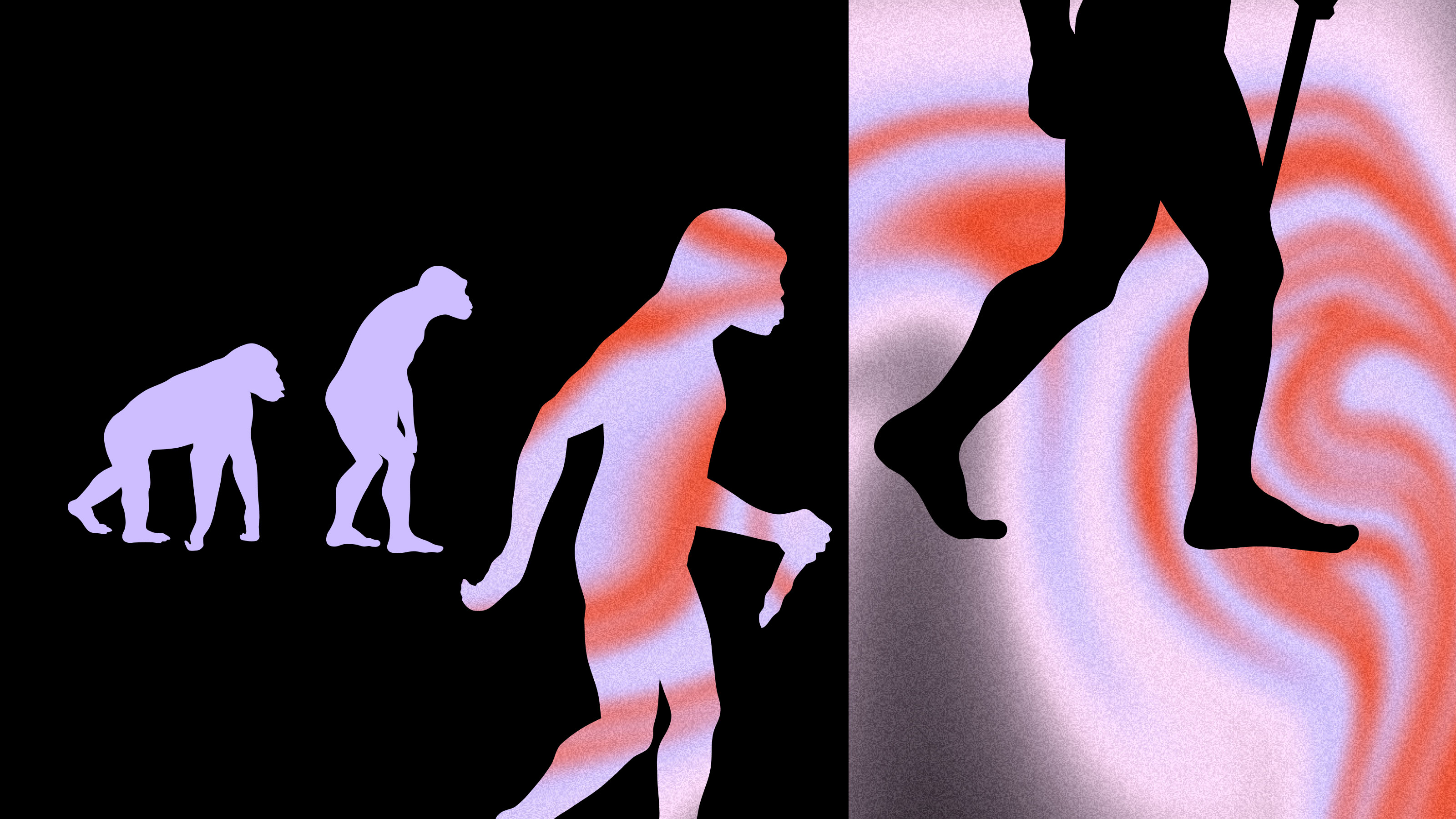

There are several ways we can classify a conspiracy theory: how scientific is it? How many people believe in it? How plausible is? But one I’m going use is a somewhat subjective measure of how extreme the theory is. I’m going to rank them from 1 to 10, with 1 being entirely mainstream to 10 being the most obscure extreme fringe theory you can fathom.

This extremeness spectrum is not simply a spectrum of reasonableness or scientific plausibility. Being extreme is being on the fringe, and fringe simply denotes the fact that it’s an unusual interpretation and is restricted to a small number of people. A belief in religious supernatural occurrences (like miracles) is a scientifically implausible belief, and yet it is not considered particularly fringe.

Let’s start with a simple list of actual conspiracy theories. These are ranked by extremeness in their most typical manifestation, but in reality, the following represent topics that can span several points on the scale, or even the entire scale.

- Big Pharma: The theory that pharmaceutical companies conspire to maximize profit by selling drugs that people do not actually need

- Global Warming Hoax: The theory that climate change is not caused by man-made carbon emissions, and that there’s some other motive for claiming this

- JFK: The theory that people in addition to Lee Harvey Oswald were involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- 9/11 Inside Job: The theory that the events of 9/11 were arranged by elements within the US government

- Chemtrails: The theory that the trails left behind aircraft are part of a secret spraying program

- False Flag Shootings: The theory that shootings like Sandy Hook and Las Vegas either never happened or were arranged by people in power

- Moon Landing Hoax: The theory that the Moon landings were faked in a movie studio

- UFO Cover-Up: The theory that the US government has contact with aliens or crashed alien crafts and is keeping it secret

- Flat Earth: The theory that the Earth is flat, but governments, business, and scientists all pretend it is a globe

- Reptile Overlords: The theory that the ruling classes are a race of shape-shifting trans-dimensional reptiles

If your friend subscribes to one of these theories you should not assume they believe in the most extreme version. They could be anywhere within a range. The categories are both rough and complex, and while some are quite narrow and specific, others encapsulate a wide range of variants of the theory that might go nearly all the way from a 1 to a 10. The position on the fringe conspiracy spectrum instead gives us a rough reference point for the center of the extent of the conspiracy belief.

Figure 3 is an illustration (again, somewhat subjective) of the extents of extremeness of the conspiracy theories listed. For some of them the ranges are quite small. Flat Earth and Reptile Overlords are examples of theories that exist only at the far end of the spectrum. It’s simply impossible to have a sensible version of the Flat Earth theory due to the fact that the Earth is actually round.

Similarly, there exist theories at the lower end of the spectrum that are fairly narrow in scope. A plot by pharmaceutical companies to maximize profits is hard (but not impossible) to make into a more extreme version.

Other theories are broader in scope. The 9/11 Inside Job theory is the classic example where the various theories go all the way from “they lowered their guard to allow some attack to happen,” to “the planes were holograms; the towers were demolished with nuclear bombs.” The chemtrail theory also has a wide range, from “additives to the fuel are making contrails last longer” to “nano-machines are being sprayed to decimate the population.”

There’s also overlapping relationships between the theories. chemtrails might be spraying poison to help big pharma sell more drugs. JFK might have been killed because he was going to reveal that UFOs were real. Fake shootings might have been arranged to distract people from any of the other theories. The conspiracy theory spectrum is continuous and multi-dimensional.

Don’t immediately pigeonhole your friend if they express some skepticism about some aspect of the broader theories. For example, having some doubts about a few pieces from a Moon-landing video does not necessarily mean that they think we never went to the Moon, it could just mean that they think a few bits of the footage were mocked up for propaganda purposes. Likewise, if they say we should question the events of 9/11, it does not necessarily mean that they think the Twin Towers were destroyed with explosives, it could just mean they think elements within the CIA helped the hijackers somehow.

Understanding where your friend is on the conspiracy spectrum is not about which topics he is interested in, it’s about where he draws the line.

The demarcation line

While conspiracy theorists might individually focus on one particular theory, like 9/11 or chemtrails, it’s very rare to find someone who only believes in one conspiracy theory. They generally believe in every conspiracy theory that’s less extreme than their favorite one.

In practical terms this means that if someone believes in the chemtrail theory they will also believe that 9/11 was an inside job involving controlled demolition, that Lee Harvey Oswald was just one of several gunmen, and that global warming is a big scam.

The general conspiracy spectrum is complex, with individual theory categories spread out in multiple ways. But for your friend, an individual, they have an internal version of this scale, one that is much less complex. For the individual the conspiracy spectrum breaks down into two sets of beliefs — the reasonable and the ridiculous. Conspiracists, especially those who have been doing it for a while, make increasingly precise distinctions about where they draw the line.

The drawing of such dividing lines is called “demarcation.” In philosophy there’s a classical problem called the “demarcation problem,” which is basically where you draw the line between science and non-science. Conspiracists have a demarcation line on their own personal version of the conspiracy spectrum. On one side of the line there’s science and reasonable theories they feel are probably correct. On the other side of the line there’s non-science, gibberish, propaganda, lies, and disinformation.

I have a line of demarcation (probably around 1.5), you have one, your friend has a line. We all draw the line in different places.