EZRA KLEIN: I think it's important that people's theories of politics are built on a foundation of a theory about human nature or some rigorous empirics about human nature. And something that I think we do a bad job understanding is the way the psychology of identity and group affiliation function in politics. We tend to suggest that identity politics is something that only marginalized groups do and in fact it's something we all do, all politics all the time is influenced by identity. In the 1930s and '40s a guy named Henri Tajfel, he was a Polish Jew, moved from Poland to France. He moved from Poland to France because in Poland he couldn't go to university because he was Jewish, in France he enlists in World War II. He's captured by the Germans, but he's understood by the Germans as a French prisoner of war so he survives the war. When he's released all of his family has been killed in the holocaust and he would have been killed as well if they had understood him to be a Polish Jew and not a French soldier. And he begins thinking and obsessing about these questions of identity what makes human beings sort each other into groups? Why when they sort each other into groups do they become so easily hostile to one another? And what does it take to sort into a group? What are the minimum levels of connection we need to have with each other to understand ourselves as part of a group and not individuals?

So, he begins doing a set of experiments that are now known as the minimum viable group paradigm. And it's a bit of an ironic term for reasons that I will get to you in a second, but he gets 64 kids from all the same school and he brings them in and he says you know we need you to do an experiment, could you look at this screen and tell many how many dots are on it just real quick do an estimation. And then researcher are busily scoring the work and deciding if the kids overestimated or underestimated. Then the researchers say hey while we've got you here would you mind doing another experiment with us not related to the first one in any way? We're just going to sort you into two groups people who overestimated the number of dots and the people who underestimated them, but a different experiment. Don't worry about it. In truth this sorting is completely random, it had nothing to do with dots, nobody cared how many dots anybody estimated. But immediately in this new experiment, which has to do with money allocation, the kids begin allocating more money, which they're not allocating to themselves it's only to other people. They begin allocating more money to their co-dot over or under estimators. And this was a surprise because the way this experiment was supposed to work was Tajfel and his co-authors we're going to sort people into groups but not enough that they would begin to act like a groups and they were going to begin adding conditions to see at what point group identity took hold. But even Tajfel, who had gone through such a searing traumatic horrifying experience with how easily and how powerfully group identity takes hold, he underestimated it, he felt this would be underneath the line almost like a control group, but it was already over the line.

This experiment was replicated by him in other ways and in other ways that actually showed not only would people favor members of their group but they would actually discriminate against the outgroup, they would prefer that everybody gets less so long as the difference between what their group and the other group got was larger. And again, these groups are meaningless and random even atop their meaninglessness. But look around, think about sports, think about how angry people get, how invested they get in their identity connection to a team that often times has no loyalty back to them that will move if it doesn't get a stadium tax break or players will leave if they get a better deal, but we get so invested in our local team and what it says about our identity and the group we're part of as fans of that team that in the aftermath of losses and wins we will riot, we will set things on fire, we will go on emotional roller coasters, we will cry, we will scream, we will listen endlessly to analysis of it. We're not there for the sportsmanship, we're there for the winning or losing, we're there for that connection to group psychology that is played out through sports and competition.

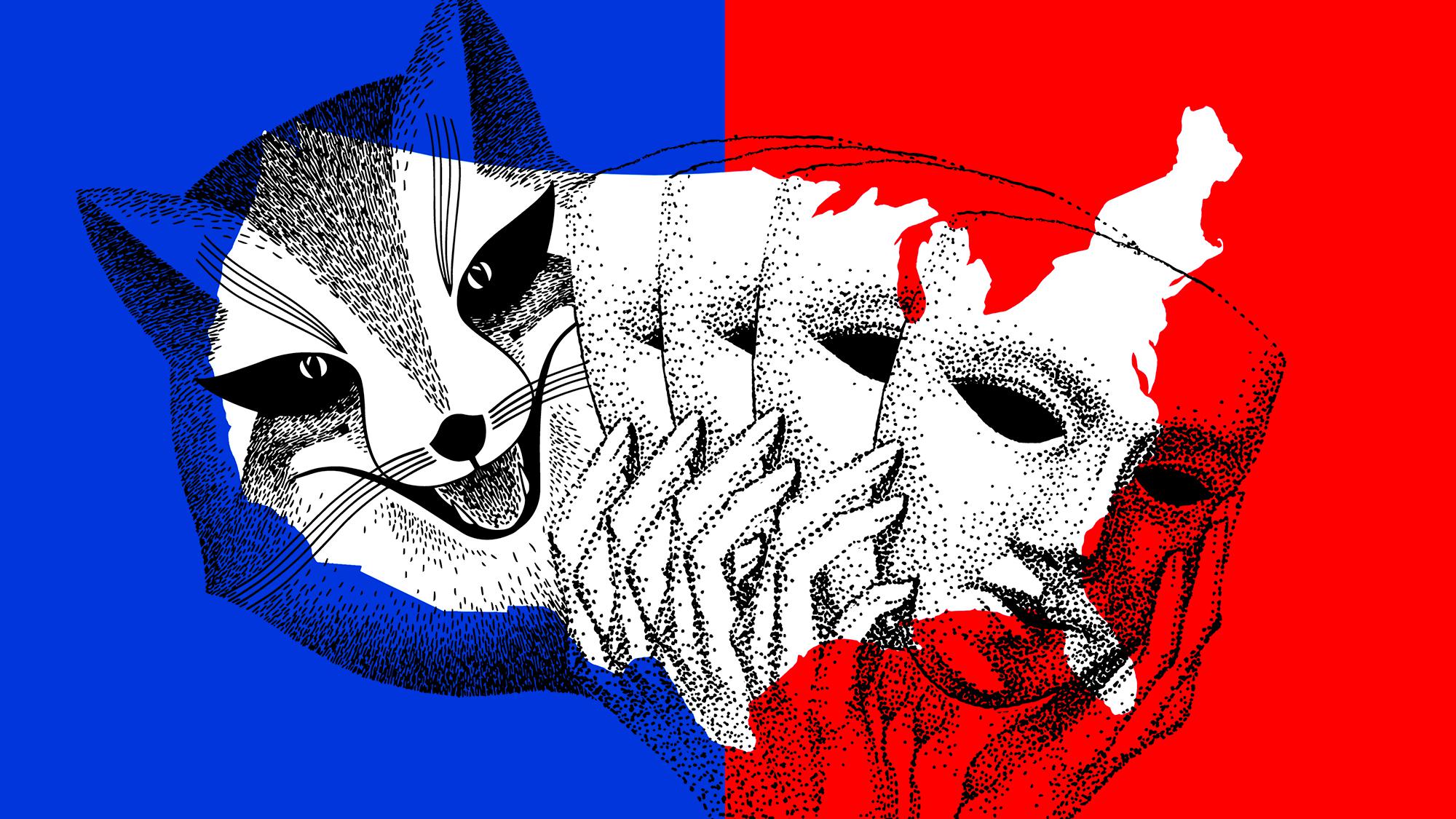

This is true in politics as well as we sort into groups as those steaks rise and become in many cases life and death as many different groups connect to one another, you're not just a Democrat but you're a Democrat and also you live in cities and also you're gay and also you're an atheist and so on, those things all begin to fuse together; it becomes what the political scientist Lilliana Mason calls a mega identity. And when you're dealing with two groups that are that sharply distinguished from each other and where the stakes are very, very high the power of that group identity and the power of the hostility to the other group becomes basically overwhelming. From a lot of different experiments we know this is a much larger driver of political behavior than even policy. We will follow parties and leaders around to policies that we didn't believe them to have just recently, I mean look at Republicans and Russia for instance, but what we will not do is change our group affiliation, certainly not easily. So, group identity is a fundamental fact about politics and it's a fundamental fact not just to the politics of marginalized groups but of majoritarian groups. An irony of our age is that we see identity politics more clearly now, not because it is stronger but because it is weaker. There is no one identity group with the power to fully dominate politics and so now that different groups are contesting they're all putting forward claims, they're all fighting for control, we can see that there is identity in our politics, but there always was it's just that when one group is strong enough they're able to make that identity almost invisible and just call it politics.