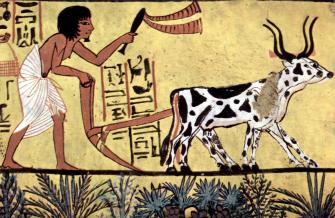

If you hate your job, blame the Agricultural Revolution

Credit: SAM PANTHAKY via Getty Images

- For the species Homo sapiens, the Agricultural Revolution was a good deal, allowing the population to grow and culture to advance. But was it a good deal for individuals?

- Hunter-gatherers likely led lives requiring far less daily work than farmers, leading one anthropologist to call them the “original affluent society.”

- The transition from hunter-gatherers to farmers may have occurred as a kind of trap in which the possibility of surplus during good years created population increases that had to be maintained.

Global warming is on track to drive lots of changes in the future. At the darkest end of the spectrum of possibilities is no future at all. That doesn’t mean that humanity goes extinct, but it does mean the big project of civilization we’ve been working on since the Agricultural Revolution 10,000 years ago might collapse. Given that scary possibility, it’s an opportune moment to look at that project with a critical eye. Yes, we have accomplished so much since we first domesticated ourselves by farming (e.g., villages, cities, empires, law, science, etc.). But is modern life worth it?

In other words, was the Agricultural Revolution a good idea?

For context, Homo sapiens appeared as a separated species about 300,000 years ago. During our entire tenure, the Earth has been undergoing a series of Ice Ages, long periods of intense glaciation where the planet was cold and dry (there is a lot of water in ice), followed by shorter interglacial periods that were warm and moist. Throughout most of those 300 millennia, human beings existed as bands of nomadic hunter-gatherers. It was only after the ice melted at the beginning of the current interglacial period (a geologic epoch called the Holocene) that we humans invented a new way of being human: farming. It was indeed a revolution, changing every aspect of being human, from how many people we might see in our lifetimes to how we spent those lifetimes.

The usual way the Agricultural Revolution gets characterized is a glorious triumph. Consider this telling of the tale.

Humans once subsisted by hunting and gathering, foraging for available food wherever it could be found. These early peoples necessarily moved frequently, as food sources changed, became scarce or moved in the case of animals. This left little time to pursue anything other than survival and a peripatetic lifestyle. Human society changed dramatically … when agriculture began… With a settled lifestyle, other pursuits flourished, essentially beginning modern civilization.

Hooray! Thanks to farming we could invent museums and concert halls and sports stadiums and then go visit them with all our free time.

The problem with this narrative, according to some writers and scholars like Jared Diamond and Yuval Noah Harari is that while the Agricultural Revolution may have been good for the species by turning surplus food into exponential population growth, it was terrible for individuals, that is, you and me.

Hunter-gatherers worked about five hours per day

Consider this. Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins once estimated that the average hunter-gatherer spent about five hours a day working at, well, hunting and gathering. That’s because nature was actually pretty plentiful. It didn’t take that long to gather what was needed. (Gathering was actually a much more important food source than hunting.) The rest of the day was probably spent hanging out and gossiping as people are wont to do. If nature locally stopped being abundant, the tribe just moved on. Also, hunter-gatherers appear to have lived in remarkably horizontal societies in terms of power and wealth. No one was super-rich and no one was super-poor. Goods were distributed relatively equally, which is why Sahlins called hunter-gatherers the “original affluent society.”

Stationary farmers, on the other hand, had to work long, backbreaking days. They literally had to tear up the ground to plant seeds and then tear it up again digging irrigation trenches that brought water to those seeds. And if it doesn’t rain enough, everyone starves. If it rains too much, everyone starves. And on top of it all, the societies that emerge from farming end up being wildly hierarchical with all kinds of kings and emperors and dudes-on-top who somehow end up with the vast majority of surplus wealth generated by all the backbreaking, tearing-up-the-ground work.

Did we domesticate wheat, or did wheat domesticate us?

So how did this happen? How did the change occur, and why did anyone volunteer for the switch? One possibility is that it was a trap.

Historian Yuval Noah Harari sees human beings getting domesticated in a long process that closed doors behind it. During periods of good climate, some hunter-gatherers began staying near wild wheat outcroppings to harvest the cereal. Processing the grains inadvertently spread the plant around, producing more wheat next season. More wheat led to people staying longer each season. Eventually, seasonal camps became villages with granaries that led to surpluses, which in turn let people have a few more children.

So farming required far more work, but it allowed for more children. In good times, this cycle worked out fine and populations rose. But four or five generations later, the climate shifted a little, and now those hungry mouths require even more fields to be cleared and irrigation ditches to be dug. The reliance on a single food source, rather than multiple sources, also leaves more prone to famine and disease. But by the time anyone gets around to thinking, “Maybe this farming thing was a bad idea,” it’s too late. There’s no living memory of another way of life. The trap has been sprung. We had gotten caught by our own desire for the “luxury” of owning some surplus food. For some anthropologists like Samual Bowles, it was the idea of ownership itself that trapped us.

Of course, if you could ask the species Homo sapiens if this was a good deal, like the wild wheat plants of yore, the answer would be a definitive yes! So many more people. So much advancement in technology and so many peaks reached in culture. But for you and me as individuals, in terms of how we get to spend our days or our entire lives, maybe the answer is not so clear. Yes, I do love my modern medicine and video games and air travel. But living in a world of deep connections with nature and with others that included a lot of time not working for a boss, that sounds nice too.

So, what do you think? Was the trade-off worth it? Or was it a trap?