Exposing our hidden biases curbs their influence, new research suggests

Image source: Hinterhaus Productions / Getty

- A study finds that even becoming aware of your own implicit bias can help you overcome it.

- We all have biases. Some of them are helpful — others not so much.

When we talk about a bias, what we’re talking about, as Harvard University social psychologist Mahzarin Banaji puts it, is a shortcut our brain has created so that we don’t have spend time and energy thinking about how we feel each time we encounter something — we have an opinion already formed and ready to use.

Many of these shortcuts are useful: A bias against hangovers, for example, has one refusing alcohol without having to think about it. The problem is the brain does a lot of this shortcutting, silently. What’s more, it creates shortcuts for people different than ourselves, sometimes based on actual personal experience, but often based on incorrect information we’ve unknowingly absorbed: other peoples’ opinions, media depictions, cultural attitudes, for instance.

Worst of all, this kind of bias may be created and deployed without our even being aware of it — it’s implicit in our actions in spite of ourselves and our conscious intentions.

Our brains don’t always get things right. We make errors in judgement all of the time. An accurate bias is a great time-saver. An inaccurate bias is a serious problem, especially if it causes us to unknowingly discriminate against others. For instance, the systemic assumptions about women that keep them from advancing in scientific fields.

Image source: Radachynskyi Serhii / Shutterstock / Big Think

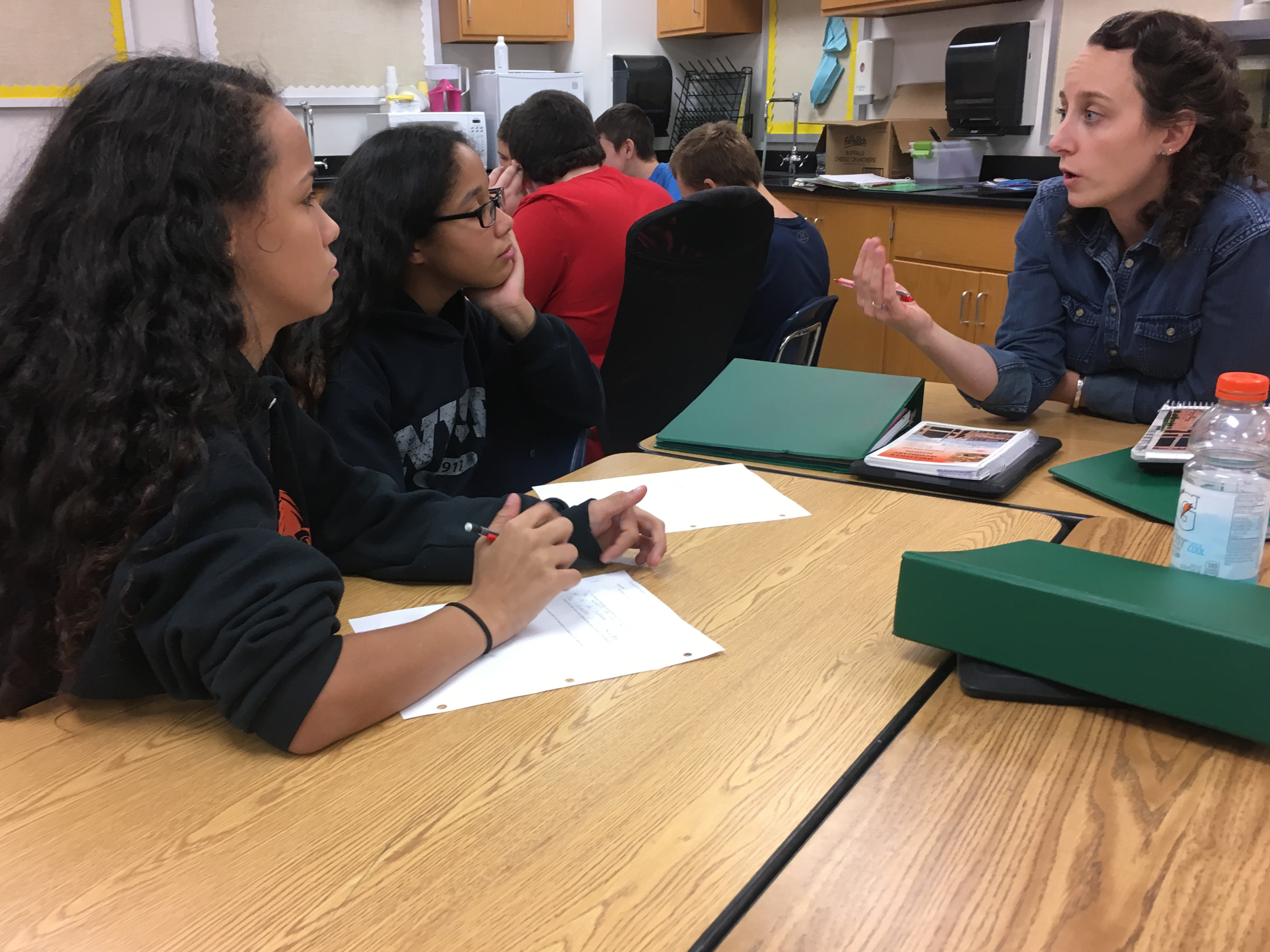

How we can curb the effects of implicit biases

New research, published in Nature Human Behavior on August 26, suggests the gender bias, which continues to prevent women from advancing in science, has a lot to do with its hidden underbelly — human blindspots. During the study, French researchers discovered that more women were promoted after the scientists in charge of awarding research positions became consciously aware of the impact of their implicit bias.

When it was no longer being highlighted, their biases discriminatory effect re-asserted itself, with award grants regressing to their traditional, pro-male pattern. Other research suggests that diversity training doesn’t really help and may even exacerbate the problem it seeks to address.

We can glean a new approach, though — one that could result in better outcomes — from the new research.

Image source: Tartila/Shutterstock/Big Think

About the study

What the new study encouragingly reveals is that a conscious awareness of one’s own hidden bias can mitigate its effect. The mechanism, it would appear, is that awareness may not delete the bias so much as make it less implicit, or unconscious.

The study looked at the awards handed out during annual nationwide competitions for elite French research positions. There were 414 people on the committees altogether, assessing candidates’ worthiness across a spectrum of research specialties — “from particle physics to political sciences.” The study analyzed committee-level data without digging too deeply into whether a committee was internally gender-balanced. The assumption was that the consensus decision reached by group represented the outcome of its internal makeup, whatever that may be.

The study took place over two years. In the first year, committee members were given Harvard’s implicit association test (IAT), which established there was a significant implicit gender biases among them. Nonetheless, that year, the influence of such biases appeared to be significantly suppressed in the awards the committees handed out.

To the researchers, this outcome suggested that simply being aware of one’s own implicit biases may take away their invisibility — the callout could make the bias more apparent and, therefore, something that can be more readily over-ridden.

The second year of the study, from the subjects’ point of view at least, was quite silent. The researchers were still watching, but the issue of implicit bias wasn’t called out. What ended up happening? The committee members returned to awarding more positions to men than women. A regression, it seemed.

It should be said, there are some possible flaws in the study: Perhaps the committee members were simply on their good behavior the first time around — until they thought that they were no longer being observed. Additionally, the study notes that there were more male submissions to the committees than female, which could skew the test. Further studies will need to be done to get a more accurate picture.

Nonetheless, the study’s authors do conclude that becoming aware of one’s own implicit biases may be the first step — maybe the most essential step — needed to overcome them.

Image source: AlexandreNunes / Shutterstock / Big Think

How do I know if implicit bias is affecting my judgement?

While the study looked at gender bias, of course, it’s not the only variety to be concerned about, others pervade our culture: race bias, ethnicity bias, anti-LGBTQ bias, age bias, anti-Muslim bias, and so on. There are a couple of online methods available for sussing out our own. Note that if the researchers are correct, then just making yourself aware of your implicit biases can help you combat them.

The IAT mentioned above is one widely used way to identify your own bias issues. Project Implicit — from psychologists at Harvard, the University of Virginia, and the University of Washington — offers a self-test you can take. Be aware, though, that the IAT requires multiple tests to produce a meaningful result.

If you’re willing to invest a little time, there’s also the “bias cleanse” offered by MTV in partnership with the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. It’s a seven-day program aimed at helping you sort out implicit gender, race, or anti-LGBTQ biases you may be harboring. Each day you receive three eye-opening email thought exercises, one for each type of bias.

Side note: Did you know that more people die in female-named hurricanes because they’re typically perceived as less threatening? We didn’t.

Step 1

It’s a well-worn bromide that simply acknowledging you have a problem is the first step to solving it, but the new study provides supporting evidence that this is especially true when dealing with implicit biases — a pernicious, stubborn problem in our society. Our brains are clever beasties, silently putting together shortcuts that reduce our cognitive load. We just need to be smarter about seeing and consciously assessing them if we can ever hope to be the people that we hope to be. That may mean, on occasion, being humble enough to receive feedback in the form of callouts.