How the internet changed our language

- The language we use is determined by “weak tie” relationships, that is, with strangers and interlocutors. For the first time in history, the internet provides an entire world of weak ties.

- The result is that internet language has evolved in different stages. If you remember MUDs, AIM, or Habbo Hotel, you might remember internet language differently.

- “Lol” has a huge variety of linguistic uses, and it is a fascinating example of how internet vocabulary serves IRL (in real life) needs.

If someone threatened to imprison you, gouge out your eyes, and then murder you, what would you say in reply? Chances are that you’ll pull out your favorite four-letter comebacks, but I doubt you would use the word “naughty.” We call people naughty when they’re being a nuisance or impish (or, in a different context, sexually adventurous). It’s also a word reserved for children who don’t eat their vegetables, not for executioners and mutilators. Yet this is exactly how Shakespeare uses it in King Lear.

This is just one example of something called semantic shift. It occurs when a certain word gradually changes over many years until, one day several centuries later, it means something completely different. “Naughty,” in Shakespeare’s England, was to be a “naught person” — a soulless, wicked, half-man. There are many other examples, too. “Awful” and “awesome” once meant the same. (They both meant “awesome.”) To be “generous” once meant to be of noble and pure blood. (Only they could be magnanimous, you see.) If you were “disappointed” you were quite literally removed from office — you were fired.

There’s a lot more fun where this came from on Etymology Online.

When tankers become a speedboat

Though semantic shift happens over centuries, it’s often easy to see the route it takes. Language has always changed, but it does so as a slow trawl and rarely ventures far. Semantic shift operates like a tree, growing slowly but resolutely, and it’s only with the time-lapse of retrospection that we can see how far it has come. Sometimes, the process is so slow as to be practically stationary. Modern Icelandic, for instance, has changed so little that your average Icelander would have no great difficulty reading the Saxon Beowulf.

But then, at the end of the 20th century, something peculiar happened to the world. Suddenly the tiny, isolated communities and regional variations were thrown together. We had the internet.

Strong and weak ties

In 1986, the linguists James and Lesley Milroy coined two terms: strong ties and weak ties. Strong ties are the friends and relatives you see all the time, the ones who probably speak like you and use the same words. Weak ties are the people you meet irregularly, the outsiders and strangers we talk to once in a while. What the Milroys argued is that weak ties are what introduce new, or different, linguistic rules. If you only spoke to your family all your life, your language wouldn’t evolve much at all. Bring in someone new, and things changes.

According to linguist Gretchen McCulloch in her book Because Internet, “The internet, then, makes language change faster because it leads to more weak ties… [and] you can get to know people who you never would have met otherwise.” With hashtags, viral videos, and “following” strangers, we are constantly rubbing up against people of different linguistic communities. Whereas before we would only occasionally meet or form these “weak ties,” now we’re swimming in a sea of linguistic foreigners and interlocutors.

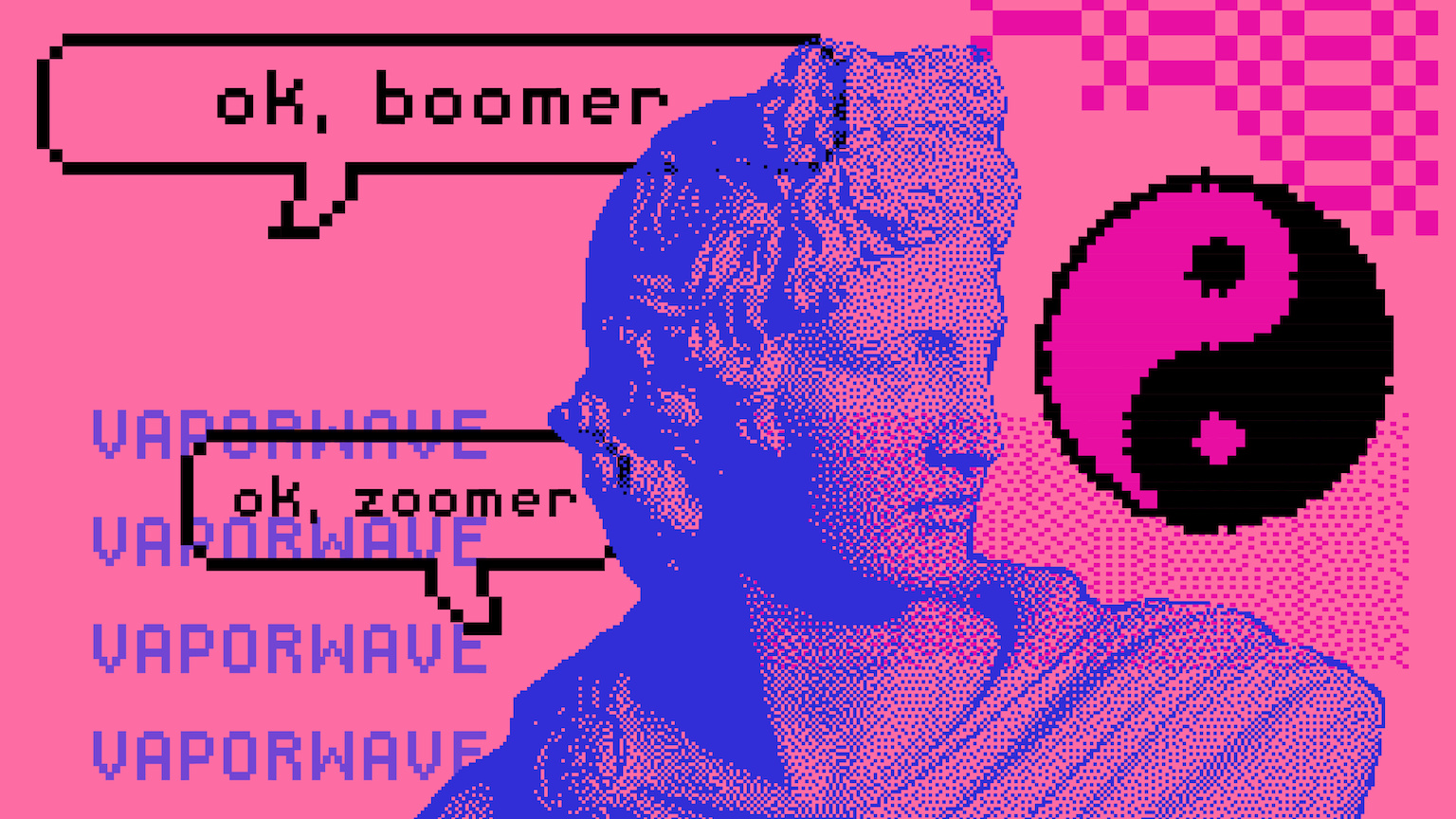

The generations of internet users

Whenever there is a new invention, there is also a jostling and negotiating about what etiquette ought to govern its use. When the telephone was invented, for instance, Thomas Edison thought conversations should start with a shepherd’s “Hello!” while Alexander Graham Bell argued for a nautical “Ahoy!” (something I feel sad he lost out on). The internet is no different.

According to McCulloch, there have been five identifiable generations of internet users, each contributing their own bit to internet language. I have whittled them down to three:

Old Internet People. They were the early adopters of the internet. Because few of their IRL (in real life) friends were online, these people needed to use “topic-based tools like Usenet, Internet Relay Chat (IRC), Bulletin Board Systems (BBSes), Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs), listservs, and forums” to reach out to strangers. Usenet was the most common, serving as an ancestor to Reddit and Google Groups (which ended up replacing it). The language the Old Internet People used was pretty similar to that used by programmers. As McCulloch tells us, “Some of its words are slang of the day, such as ‘win’ meaning ‘succeed,’ and computer slang that later entered the mainstream, like ‘feature,’ ‘bug,’ and ‘glitch.’ Others are hacker cultural terms, like ‘foo’ and ‘bar’ as placeholder names.”

Social internet. The main difference between this generation and the previous is in seeing the internet as a social medium. The Old Internet People mainly kept their social lives offline, but the second wave turned to MSN, AOL/AIM, MySpace, and WeBlog to connect with friends as well as strangers. Slowly, MySpace gave way to Facebook and Twitter, via social gaming sites like NeoPets and Habbo Hotel. It was within this context of social interaction that “abbreviations like ‘lol’ and ‘wtf,’ emoticons like 🙂 and <3, and conventions like all caps for shouting” came into being. Differences and debates emerged at the beginning. Was it “L.O.L.” or “lol”? Should you capitalize or hyphenate E-mail/email? What was the etiquette for writing emails vs. normal letters? As with language in the real world, eventually norms were established, and now it feels weird to read things any other way.

Post-internet. If you can remember joining social networks when they were still unpopulated, niche, fledgling things, then you likely belong to the above generation. If, though, you joined an already bustling online world of social networks, this is your generation. In this group, there are two noticeable clusters: the first is the “Facebook cluster” (which includes Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube), and the second is the “Instant Messaging” cluster (which includes Snapchat, Instagram, iMessage, and WhatsApp). According to research done by McCulloch, about one-third of 18-23 year-olds identify with the Facebook cluster and half with the Instant Messaging cluster.

The depth to lol

In the post-internet generation, funny things happened to the expression (word?) “lol” — which was definitely lowercase by now. Linguistically, it serves a fascinating variety of functions.

Of course, it still acts as an expression of laughter and enjoyment. You can reply to a joke with “lol” and capitalize or give it an exclamation mark if you really liked it. But “lol” also has other uses. It is a way to soften a potentially misread or offensive message, as in, “You were so drunk last night lol.” It can be a way to flirt: “You look good in red lol.” It can express or underline sarcasm, “This lecture is so fun lol.” It can even be passive-aggressive, “You better buy me a present lol.”

The internet is, in many ways, a Wild West of on-the-hoof rules and decentralized authority. But language still operates in the same way. New words or uses collide together through extensive “weak ties,” and then usage will determine what sticks and what doesn’t. Words like “lol” show us that certain metalinguistic functions are also emerging to work around the text or digital-only medium.

People will always want to talk the same way, and language still follows certain patterns. The internet is different in speed but not in kind.

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.