Are big cities bad for our mental health?

- People living in cities are more susceptible to mental illness than their countryside counterparts.

- Sociologist Georg Simmel suggests this is because the city, a place of excessive stimulation, has a special way of rendering people indifferent to the world around them.

- Where relationships in towns are characterized by emotions, those in cities are purely economic — and its inhabitants are poorer for it.

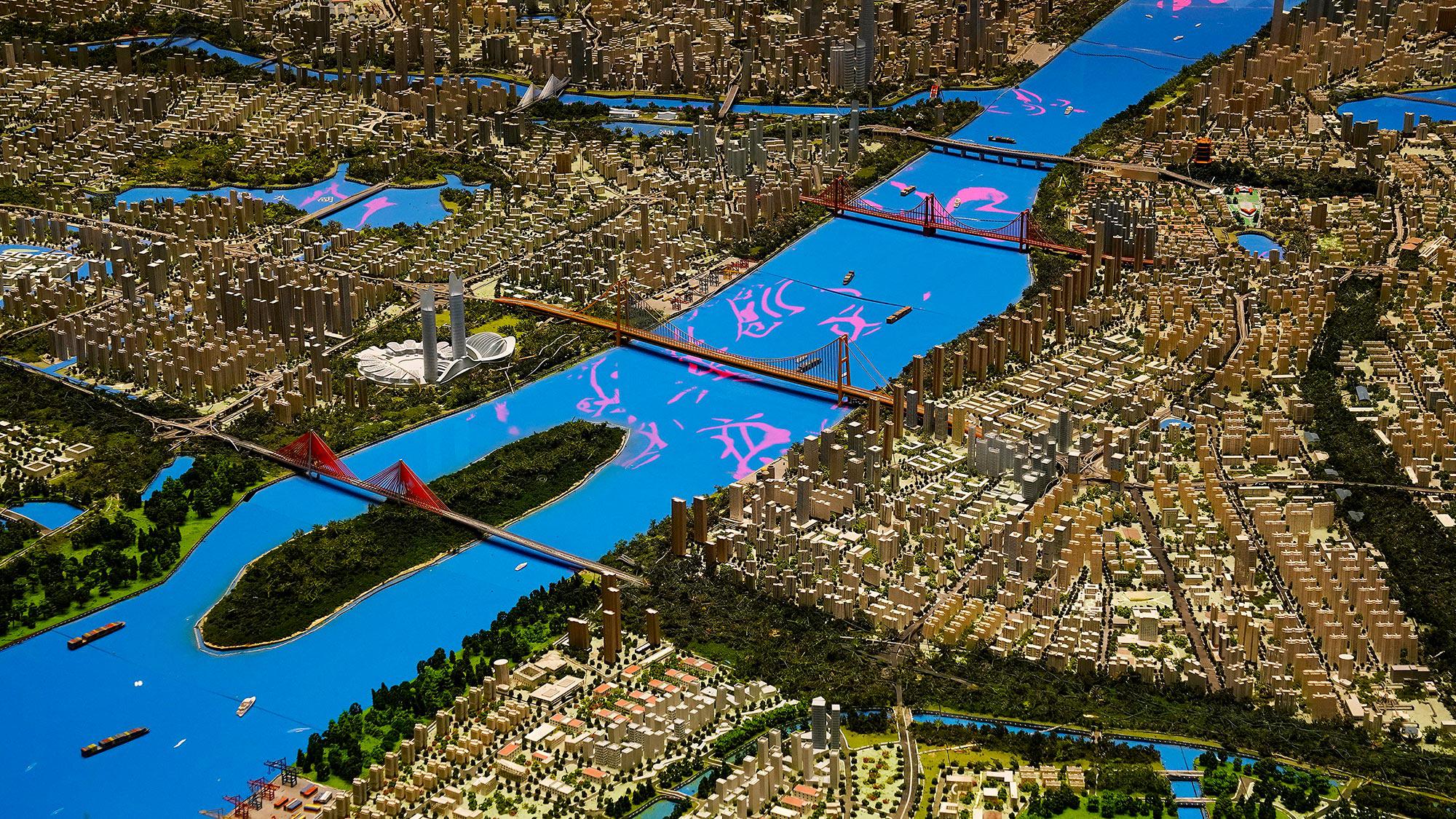

Research accumulated by the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health confirms it: People living in big cities are far more susceptible to mental illnesses than those living in more quiet, rural areas. Specifically, city-dwellers are almost 40% more likely to suffer from depression and other mood disorders and twice as likely to develop schizophrenia.

For decades, psychologists, philosophers, and urban planners have hypothesized as to why urban environments could be associated with poor mental health. During this time, many viable explanations have been brought forth. For one, city-dwellers are routinely placed in emotional states that eat away at their psychological wellbeing, such as stress, isolation, and uncertainty.

How exactly city life brings out these conditions is not at all clear. While some people move to the city in search of opportunity, others do so to escape intolerable conditions such as war, poverty, or abuse. Rather than curing their neuroses, however, the perils and pitfalls of city life may actually have the adverse effect of exacerbating them.

At the same time, there seems to be something about cities that brings out the worst in people regardless of whether they arrived with predetermined trauma in tow. One of the academic texts which comes closest to describing this “something” is “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” an essay that was published in 1903 and written by the German sociologist Georg Simmel.

Georg Simmel and the blasé outlook

Growing up in the burgeoning metropolis of Berlin during the so-called Belle Époque, Georg Simmel did not share his contemporaries’ unwavering belief in civilization. Where others saw society as continuously improving with the help of science and commerce, Simmel could not help but feel as though humanity had taken a wrong turn and was now paying for its mistake.

Simmel attempted to elucidate this position in “The Metropolis,” which originally came into being as a lecture for Dresden’s First German Municipal Exposition, a cultural and industrial showcase for the development of German cities. Asked to discuss the role of academia in tomorrow’s cities, Simmel settled on a different, more critical take on the subject.

In the essay, Simmel compares living in a rural village to a big city and tries to show how each environment shapes the psychology of its inhabitants for better or worse. His central thesis is that city-dwellers, because they are exposed to so many more audiovisual stimuli than their countryside counterparts, involuntarily erect psychological defenses against their surroundings that make life less rewarding.

Likening the human nervous system to an electrical circuit, Simmel supposes that this system — if overstimulated for a prolonged period of time — will cease to function. As a result, things that once emotionally or intellectually stimulated the city-dweller quickly cease to excite them. Simmel refers to this outlook as blasé, but today, people also use the term jaded.

“The essence of the blasé attitude,” writes Simmel, “is an indifference toward the distinctions between things. Not in the sense that they are not perceived, as is the case of mental dullness, but rather that the meaning and value of the distinctions between things… are experienced as meaningless. They appear to the blasé person in a homogeneous, flat and grey color.”

Money as the frightful leveler

This attitude is partly the result of overstimulation and partly a defense mechanism against it. The number of people which city-dwellers must interact with on a daily basis is so large that it is both impossible and impractical to develop a personal connection with every one they meet. Consequently, most interactions with others are brief and impersonal.

This is in sharp contrast to the village, where inhabitants are intimately familiar with each other. For instance, a baker is not just a baker but also a neighbor. He is not simply a member of the service industry that sells bread in exchange for money, but a member of the community, and his personality and history are as (if not more) important to customers than the service he offers.

While relationships in towns are governed by emotions, those in cities are based on reason. “All emotional relationships between persons rest on their individuality,” writes Simmel, “whereas intellectual relationships deal with persons as with numbers, that is, as with elements which, in themselves, are indifferent, but which are of interest only insofar as they offer something objectively perceivable.”

Because city-dwellers are unable to establish meaningful relationships with a large number of people in their vicinity, their interactions with different elements of society become economic rather than communal. Where townspeople can place their trust in one another, city-dwellers can rely only on the sanctity of their transactions and the value of their currency.

Georg Simmel refers to currency as “the frightful leveler” because it expresses everything in the same monetary unit. Goods and services, rather than being unique to the person that provided them, acquire a value that can instantly be compared to all other things. Thus, the market economy, fully developed in big cities, also contributes to the city-dweller’s inability to distinguish their surroundings.

The price of polity

To offer an example of a complex society that did not have a similarly deteriorating influence on its inhabitants, Simmel had to travel all the way back to Ancient Greece. The antique concept of the polis or city-state, perhaps because it was always threatened by other municipalities, seems to him to have offered a mode of being that did not exclusively revolve around money.

Modern cities are built on individuality, which is expressed in the specialization of its labor as well as the financial independence of its inhabitants. The polis, by comparison, was more like a large, small town. Rather than separating its populations into distinct economic units, these city-states promoted the notion that everyone was part of the same social institution.

As the world’s metropolises continue to grow, so too do the public health crises that fester in their bowels. “The deepest problems of modern life,” Georg Simmel wrote more than 100 years ago, “flow from the attempt of the individual to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence against the sovereign powers of society, against the weight of the historical heritage and the external culture and technique of life.”

This attempt to remain independent is, of course, a double-edged sword. While city-dwellers have more economic freedom compared to townsfolk, that freedom comes at a hefty cost. Without the personable and supportive networks found in the country, cities are transformed into psychological minefields. One wrong step, and its inhabitants can fall pray to loneliness, purposelessness, or — worst of all — indifference.