Inside the secret cities that built the atomic bomb

Wikimedia Commons/Big Think illustration

- Highly secretive, closed cities were used during the Cold War to develop nuclear-grade plutonium and uranium.

- Oak Ridge and City 40 — two such cities — highlight the world-altering impact of nuclear weapons.

- Vacationing in the East Ural Mountains? Bring a Geiger counter.

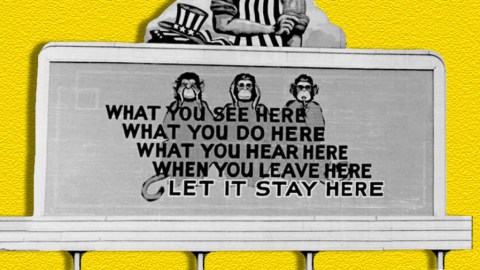

In 1942, the U.S. Government bought 60,000 acres of land in rural Tennessee. On it, they began to build thousands of small homes, grocery stores, schools—basically the makings for a small town. It wouldn’t have been all that remarkable, except for the military checkpoints places at all roads leading into the town, the billboards of a beefy Uncle Sam imploring citizens to keep quiet about their work, and the massive, sprawling facilities. Most notable was the 44-acre facility codenamed K-25. At the time, it was the largest building in the world.

Specific types of people began to move in—physicists, engineers, construction workers, medical staff, and other professionals. K-25 was the hub of their existence, and, although most did not know it, they were there to produce weapons-grade uranium.

Women at the Oak Ridge facility operating calutrons, devices used to separate uranium isotopes from uranium ore.

(Wikimedia Commons)

A secret, atomic city

Administrators settled on “Oak Ridge” as the town’s name due to its rural innocuity. Over the ensuing years, Oak Ridge grew at a precipitous rate. By 1945, the town had accrued 75,000 citizens, all of whom were either employed at K-25; other, ancillary nuclear production facilities; or were family members of the employees.

The work was complicated enough that most employees had no idea what they were working on. There were rumors that they were working on some kind of synthetic rubber, but there was no way to verify this. The nuclear production facilities were unaware of the work the other facilities were doing. Within the plants themselves, everything was compartmentalized to prevent anybody from piecing things together. In an interview with New Republic, one surviving worker recalled:

“There was a time, coming home from the lab, when I couldn’t talk to my wife at all. I pretty well knew what the Project was making, but I couldn’t tell you. We’d sit around the dinner table and the strain was terrible. A man could bust. Then we started quarreling. Over nothing, really.”

Of course, some people knew what was going on, but they had been sworn to secrecy. However, with 75,000 people working on a project of the utmost interest to the world at large, not everyone could be trusted.

The sleeper spy at Oak Ridge

Despite the many security measures taken to keep Oak Ridge and its work a secret, the project was ultimately infiltrated by the Soviet Union. George Koval, an American born to Russian immigrants, was eventually recruited by the GRU—the Soviet military intelligence agency—and joined the U.S. military with the intent of gaining access to information about chemical weapons.

Koval was talented, and the Army quickly inducted him into several technical training groups. Ultimately, he was assigned to Oak Ridge to work as “health physics officer”. Essentially, his work was to monitor levels of radiation throughout the entire K-25 facility. With practically unlimited access, Koval gathered a significant amount of technical information about the construction of an atomic bomb. He, along with other spies, fed this information back through his handlers, and he is credited with drastically advancing the Soviet’s nuclear developments.

Warning sign posted on the edge of the East Ural Radioactive Tract, alternatively referred to as the East Ural Nature Reserve.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The Soviet’s desolate City 40

Nearly 6,000 miles away, in an isolated part of the Ural Mountains, the Soviet Union was scrambling to develop their own Oak Ridge and K-25. The first step was to build Mayak, a nuclear facility where plutonium could be refined to make a bomb. In 1946, the Soviets built a city to house the many people who would be working at the plant. In contrast with the provincial Oak Ridge, the Soviets opted for the no-frills name of “City 40.” Later, however, it would be referred to as “the graveyard of the Earth.”

City 40 contained 100,000 Soviet citizens, but the city itself did not appear on any maps, and the names of the citizens living and working there were erased from the Soviet census. For the first eight years of their work there, the citizens were forbidden from leaving the city or contacting the outside world in any way. As a result, little is known about the nature of life in the city. However, it is known that the people working there lived a life of relative luxury compared to the rest of the Soviet Union. They were fed well, had decent healthcare, and their children went to good schools.

All of this came at a terrible price. Because the Soviets were in a rush to catch up to the United States, the Mayak production facility was built and operated in extreme haste. The emphasis was placed on producing enough weapons-grade material to compete with the United States, rather than worker safety.

Although Koval and other spies gathered critical information for the development of atomic bombs, the information was incomplete, and the dangers of nuclear production were not fully understood. As a result, the Chelyabinsk region, in which Mayak and City 40 are located, is considered to be the most polluted place on Earth.

Workers at the Mayak plant dumped nuclear waste into a nearby river. Water from the nearby Lake Kyzyltash was used to cool the nuclear reactors, after which it was returned to the lake. Underground storage vats were built to contain nuclear waste, but these could not contain all of the radioactive material produced at the site. Instead, the excess material was dumped into the nearby Lake Karachev.

It wasn’t long before something failed. Disastrously, the failure point was a cooling system in one of the storage vats for the nuclear waste. As the temperature slowly crept up, so too did the pressure. Eventually, the vat exploded with the force of 100 tons of TNT, spreading radioactive material throughout the area in an event called the Kyshtym disaster. The radioactive contamination produced by the explosion and the general pollution of the plant are estimated to be two to three times greater than that produced by the Chernobyl disaster.

The red area indicates the spread of nuclear material from the Kyshtym disaster. In the lower left section of the map, the Mayak facility is pointed out (labeled “Kerntechnische Anlage Majak“).

Many cities and villages in the region unknowingly used the poisonous rivers and lakes for washing and drinking water. Villagers began to catch mysterious diseases they could not explain nor treat. Eventually, they were evacuated, but the process was slow, taking between two weeks and two years, and the evacuees were not told why they had to leave their homes and all their possessions behind.

The exact number of casualties isn’t known. It is estimated that between 50 to 8,000 were killed by the Kyshtym disaster alone. In an effort to keep people out and to disguise the disaster, the Soviets ironically referred to the EURT as the East Ural Nature Reserve and required special passes for entrance to the region. Information on the disaster, City 40, and EURT was only released by the Soviet Union in 1989. Today, City 40 is called Ozyrosk, and many people still live there in relative good health. Take out a Geiger counter, though, and you’ll hear plenty of chirps and crackles.