Too much choice: The strange phenomenon of “analysis paralysis”

- We are often terrified by choices. When we’re forced to choose, we’re forced to decide who we want to be.

- Our brains are not designed to deal with a great number of options, and so having too many choices or decisions can be a mental drain.

- For Sartre, however, we must choose. However much we might want to live in a cage, we have to choose a future.

Choice is a good thing. Imagine a world where shops had only one item, or you could only have a pre-set list of friends, or if there was only one TV channel to watch. What a dull, narrow, monochromatic world that would be. Choice and freedom are the hallmarks of a fulfilled human life. It’s even argued that the availability of choice is the best indicator of overall welfare, not to mention social justice. Having no choice means being caged or enslaved in some way.

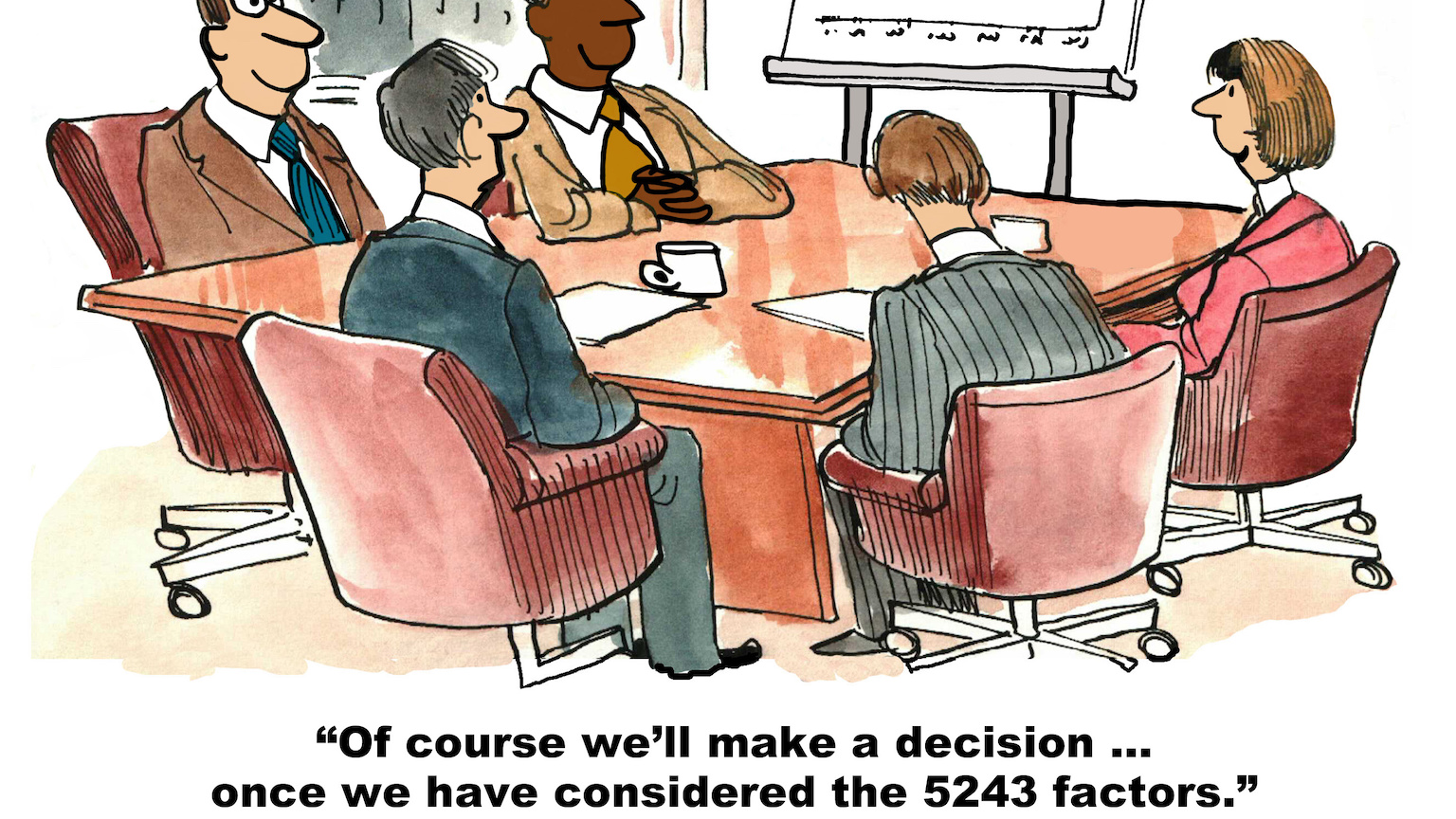

But there are few things in life that are unreservedly good. So, too, with choice. When we have too many options, when there is no magnetic pole by which to orient ourselves, we spin mindlessly and frantically about. Faced with the undefinable vastness of what we “could” do, a lot of humans go into a kind of mental breakdown — something known in the literature as “analysis paralysis.” Choice is a good thing, but too much choice makes us panic. The scale of the task given to us causes us to freeze in the headlights, and we stutter to a halt.

The expanse of the possible

The past is fixed and known. We often can accept it, hard as it may be. The future, however, is an impenetrable veil of the unknown. There is no path into the future. There is only possibility. The French philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, puts it like this: “The Future thus defined does not correspond to a homogeneous and chronologically ordered succession of moments to come… I am an infinity of possibilities [and] cannot be contained in one formula.”

The problem with choosing is that it commits you to a particular fixed course. When you stand in the present moment — at the intersection of your choice — then you still have this multiverse of possibilities stretching out before you. But when you choose, it defines you. You become someone. Life is a constant succession of choices that define who you are. It’s why, especially at those crux moments like leaving school or looking for a job, that the weight of choice feels too much. And so we get analysis paralysis.

Making the job easier

The beauty of philosophy like this is that it’s hugely relatable. From choosing which restaurant to go to all the way to what name to give your child, the open-questions of the future can be crippling. But what’s going on in your brain when it flails and panics in these moments?

The mind is a computational leviathan, and there is nothing in the known universe that can match the sheer variety of functionality it gives us. It has billions of neurons making up trillions of connections, and our memory can store as much as the entire internet. But it’s also a specific tool, evolved to a specific purpose, and so it will have more limitations than we would like.

Our brain uses a lot of energy. Despite making up only two percent of the body, it takes up 20% of all our body’s oxygen and energy. So, our body constantly implements certain energy-saving strategies or heuristics to make it a bit less of a sponge. One rather surprising upshot is that the brain is actually pretty slow at processing information. It’s designed to focus on only one or two things at once, with a special bias for novelty. This means that when we are faced with a great menu of choices, our mind struggles to cope. The brain knows all too well how bad analysis paralysis will be.

As cognitive psychologist Daniel Levitin puts it, “It turns out that decision-making is also very hard on your neural resources and that little decisions appear to take up as much energy as big ones.” We simply do not have the cognitive resources or energy to deal with lots of choice. It’s probably why having to make too many decisions feels like it hurts our head.

Our brain will try to limit this kind of analysis paralysis and thus present to us only a few options — options that are often novel, dangerous, or exiting.

Tell me what to buy!

Let’s take a practical example. It’s commonly assumed that “more choice is good” as a business model. If a shop or service presents more options, then you are more likely to get a sale given the magnificently heterogeneous demands of consumers. If you offer Coke, Dr. Pepper, and Sprite, you’re more likely to sell one compared with just having Coke. But recent research casts that into doubt. When given the option of “not buying,” it turns out that “over-choice” — an overwhelming variety of options — actually turns customers or clients away. The analysis paralysis, anxiety, and panic that results from choosing between too many options is bad.

In a world of internet shopping and tens of thousands of mobile phone cases on Amazon, which ones do you pick? Sometimes, we want someone to narrow our options down. It’s why we look at reviews, or ask a friend, or rely on some journalist to do the work for us.

Suffocating cages or anxious freedom?

For Sartre, and existentialism more broadly, this anxiety when faced with a choice places us in a Catch-22. Freedom is scary, mentally exhausting, and can lead to analysis paralysis. On the other hand, a caged life of forced choice is suffocating and oppressive. And so, we often vacillate between the two, bemoaning both, and never fully committing to either.

Many people, though, will lean toward the monotonous comfort found in the fixity of a predetermined life. As Sartre wrote, “People often prefer a very limited, punishing regime — rather than face the anxiety of freedom.” But this is not what it means to be human. For however hellish choice might seem, however terrifying the untrammeled future is, it’s the job of a human life to walk it, nonetheless.

You cannot put off tomorrow, and you cannot stop change from happening. But you can control what that change might be.

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.