Do you crave deeper knowledge? Go Zen and learn to forget

- Forgetting what we have learned is not always anti-intellectual.

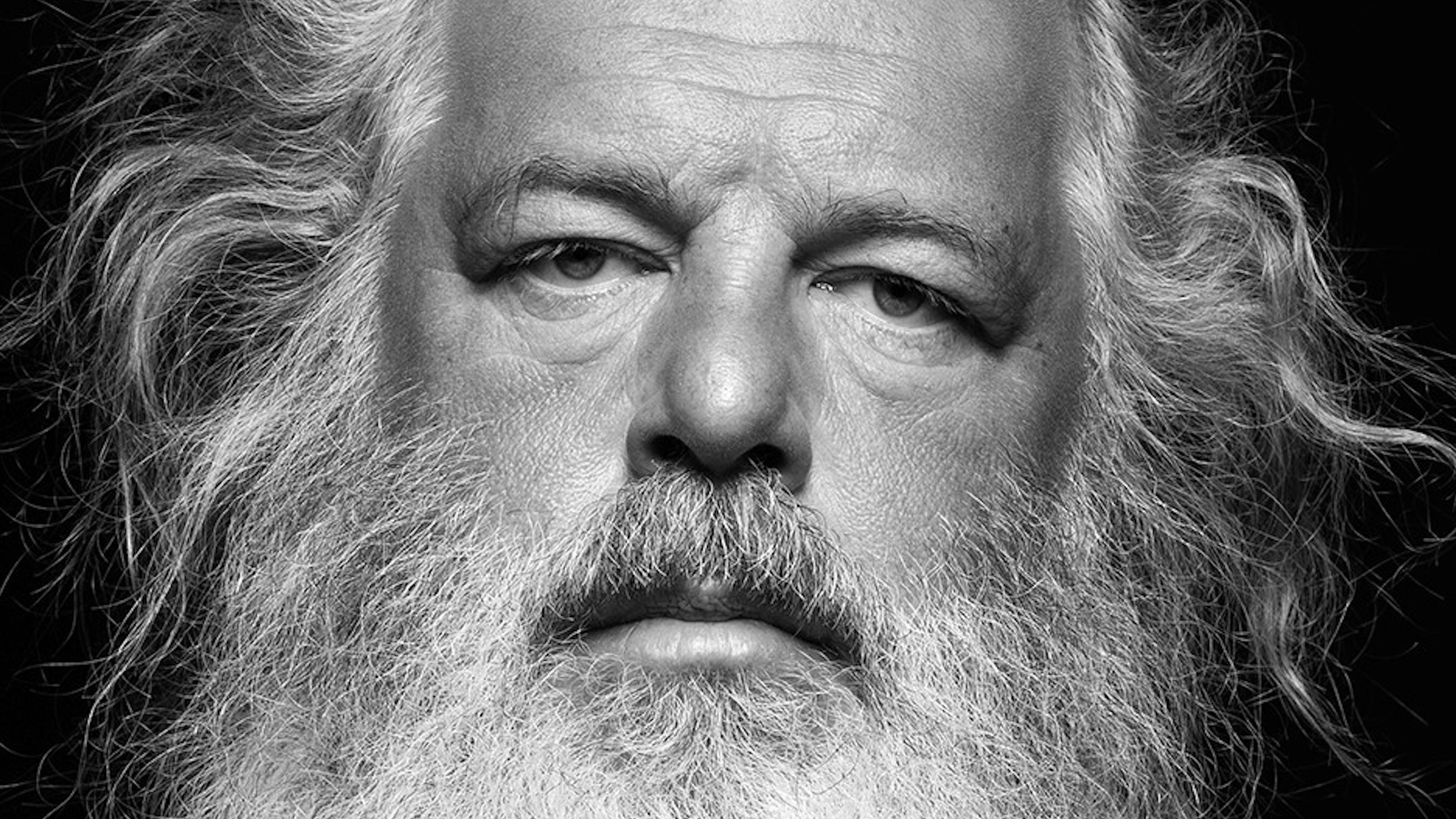

- Thinkers through the ages — from Zen master Shunryu Suzuki to Henry David Thoreau — have suggested that we cultivate “not-knowing” along with learning.

- If you don’t appreciate the importance of not knowing everything, you are going to have problems.

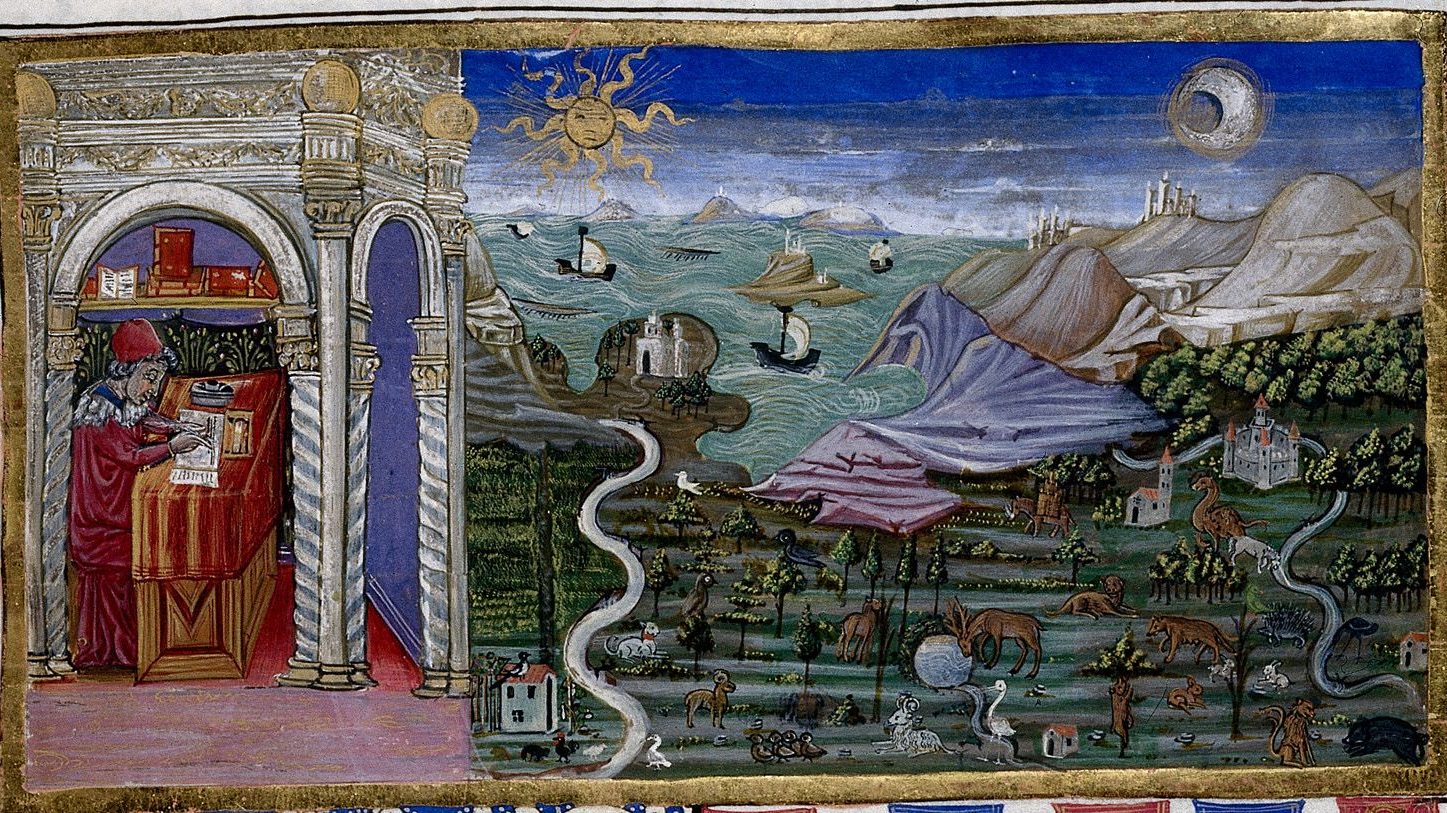

It is only when we forget all our learning that we begin to know. I do not get nearer by a hair’s breadth to any natural object so long as I presume that I have an introduction to it from some learned man. To conceive of it with a total apprehension I must for the thousandth time approach it as something totally strange.

—Henry David Thoreau

It is a good idea to forget many of the things you have learned over the years. Some are outmoded, some incorrect, some too obvious and trite. We also need a fresh approach to things of interest, to see them as if for the first time, to attain “beginner’s mind.” This approach would help make a thing “strange.”

Years ago, when I kept coming across the idea that knowledge is not a good thing, I used to wonder if this was anti-intellectualism. But I kept finding the idea in the work of many brilliant thinkers that I admired. I loved to read and study, and I knew they did. So why were they so negative about knowledge? Here is poet David Hinton’s translation of chapter 71 of the Tao Te Ching:

Knowing not-knowing is lofty.

Not knowing not-knowing is affliction.

Let me go over this beautiful translation as I understand it: If you know the importance of not knowing everything, or anything for that matter, you are way ahead. You know the most important thing. If you don’t appreciate the importance of not knowing everything, you are going to have problems. You will be under the dangerous illusion that you know what life is all about. You will have banished the mysteries that are so important. You will be full of ego, thinking that you know what you are talking about, when in fact you are only defending against your ignorance. The starting point toward wisdom is to acknowledge your basic ignorance, your not-knowing.

Let’s delve into Zen master Shunryu Suzuki’s phrase “beginner’s mind.” You can always find a frame of mind in which you are a beginner, maybe once again. You keep coming back to the role of student and novice, open to learning because there is something you know you do not know. How fruitful that attitude is. But you could discover it in any situation, acknowledging and appreciating the extent to which you don’t know something. Sometimes achieving it may require a little bruising to the ego, but that is always a good thing.

When you cultivate not-knowing along with learning, you also allow room for mystery, for the profound and inexplicable parts of life that give you a sense of awe. An appreciation of the unknowable keeps you honest and humble in the best way. It is the base of a religious or spiritual attitude and in the end makes you more human. The truly wise person knows how important it is not to know everything.

I sometimes find myself giving a lecture or speaking in an interview when I know I don’t know at all what I am talking about. Usually that is because the topic is unknowable. I often speak about the soul, for instance, yet after years of study I still don’t know just what the soul is. They ask me to talk about God, and I’m certainly at a loss there.

The trouble with some teachers and leaders is not that they don’t know what they are talking about, but that they don’t know that they don’t know what they are talking about. They go on blissfully using words that even they do not really understand, but they think they do, or at least talk as if they do.

The solution is to admit to our ignorance and try to clear our minds of preconceptions. These are Thoreau’s recommendations. Try to forget what you think you know. Don’t rely on authorities, but simply be in the presence of whatever it is you are concerned with. Finally, aim for “total comprehension” and not just acquaintance.

As I sometimes put it, knowledge from the soul is more intimate than knowledge from research and study. Both are valuable, but Thoreau is reminding us of an approach we may overlook: being closely present to the thing we are studying. I sometimes listen to professors giving speeches about psychotherapy, and yet they have never practiced it. I have been doing it for forty years and sense an important gap in their presentations, a wide gap. I do not want to say that you always have to have an experience of something before you can comment on it. Sometimes a good distance is useful. Still, there is some valuable emptiness in forgetting your information and just being present with the object of your investigation.