Surrogate activities and why we crave adventure in a comfortable world

- In our anodyne and comfortable world, humans struggle to find true satisfaction and often engage in surrogate activities to fulfill their primal desires.

- The "effort paradox" suggests that people find value and pleasure in overcoming challenges.

- By embracing effort and seeking challenges, humans may find deeper contentment and feel more connected to their nature.

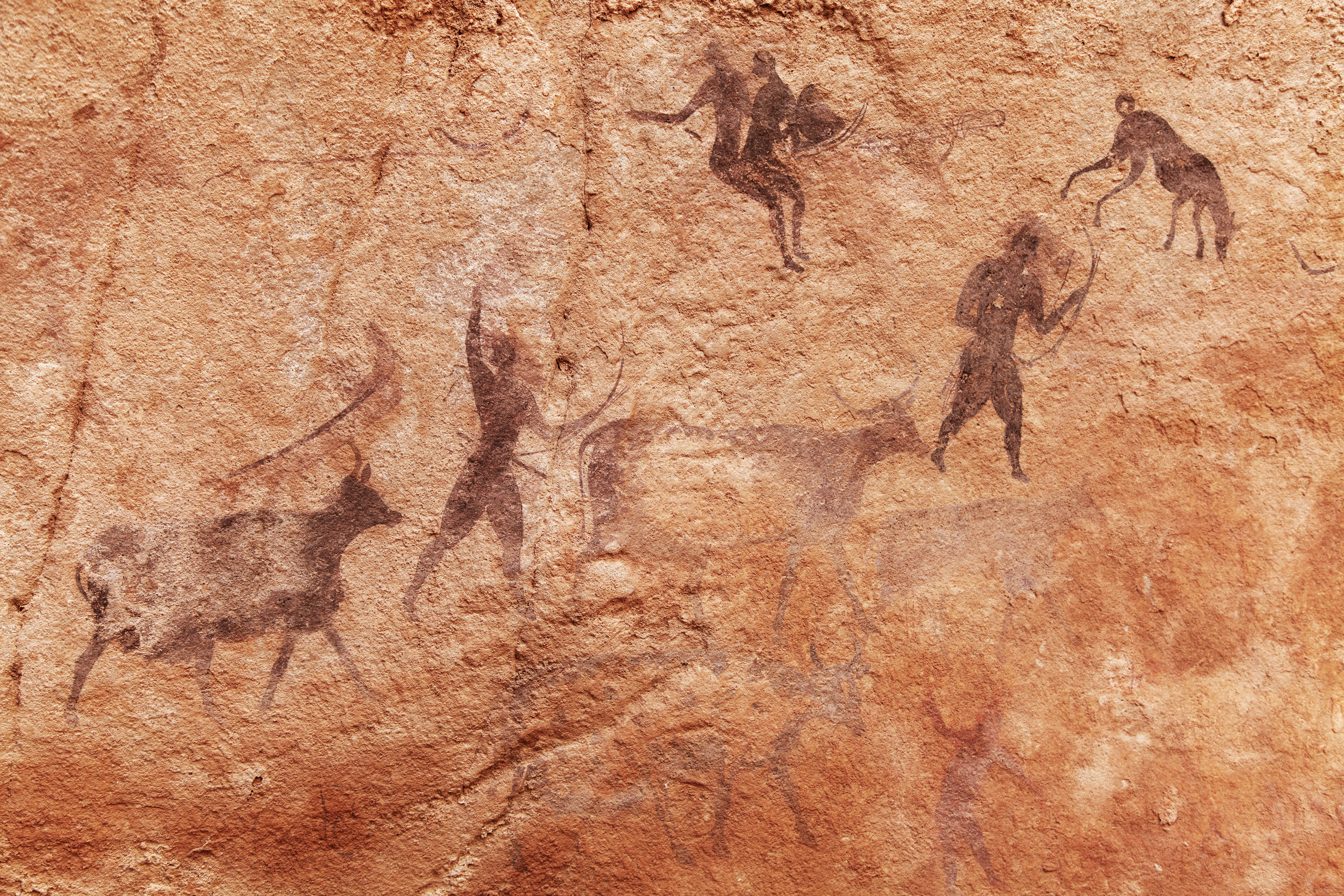

Broud stalks the beast, spear gripped tight, his breathing slow and steady. From his cover in the bushes, he can see the beast’s huge teeth and coiled muscles. It will be a challenging hunt. It might be his last. Banishing fear from his mind, Broud leaps from his hiding place and into the air. With all his might, he thrusts his spear into the beast’s back. The beast gives out a deep, primal roar as its head snaps around with feral energy. Razor-sharp claws slice a gash across Broud’s thigh, but it isn’t deep, and Broud darts back to watch the life-blood leak out from his kill. The hunt is over.

Fast forward 200,000 years, and here you are reading this article. You’re comfortable and warm and probably have a nice bed to climb into later. You have a grocery store near you that sells a vast variety of goods. You have antibiotics, refrigeration, and TVs. Never in the course of human history have humans had it so easy.

But the human spirit was not forged on sofas. Homo sapiens’ ingenuity was not tempered in glass-walled boardrooms. Our great reserves of bravery, resilience, and strength were not designed to send anonymous threats to strangers over Twitter. We are an adventure-seeking species in a world where adventures sound a bit too dangerous.

Drama queens and the death drive

There is something that doesn’t quite fit with humans. Other animals aim to find consistency in the order of things. They seek out ideal conditions and settle for as long as those conditions remain ideal. Humans, though, are not happy standing still. Even in environments designed to make our lives as comfortable as possible, we are restless.

Sigmund Freud labeled this the “death drive.” It’s the part of ourselves that needs to self-sabotage and make war. It’s the urge to smash a sandcastle and the odd desire to see some sycophantically happy couple break up. It wants to lie, cheat, insult, abuse, and then watch as the world burns simply because things are more interesting that way. For the philosopher Slavoj Žižek, this desire to explode (or implode) is the hallmark of freedom — or, at least, the need to feel free. As he writes, “The ‘death drive’ as a self-sabotaging structure represents the minimum of freedom, of a behavior uncoupled from the utilitarian survivalist attitude.”

Humans are maladjusted, discontented provocateurs. We need an enemy, and we need something to break. But as Nietzsche wrote, “In times of peace, the warlike man attacks himself.” If we have no conflict or problem in life, then we create one. When there is nothing to destroy, we destroy ourselves. When everything is happy and perfect, we can’t help but muck it up. What a strange species we are.

Man is a goal-seeking animal. His life only has meaning if he is reaching out and striving for his goals.

– Aristotle

Surrogate activities

The idea, then, is that we have a kind of combative hunter energy within us that goes unfulfilled in the modern world. It is this energy that often leads to what is called “surrogate activities.” In Aristotle’s theory, “Man is a goal-seeking animal. His life only has meaning if he is reaching out and striving for his goals.” And so, when the original goals of our nature have been denied — when we can no longer indulge our primal, base desires — we invent artificial ones. In the absence of real problems, we make up new ones.

For example, people might turn to video games to adventure in ways they cannot in real life. Someone could obsessively turn to knitting or crafts to compensate for a lack of productivity in other life arenas, such as work. We might watch or play sports that allow — and encourage — a more primal spirit of competition and aggression. A person could enjoy certain TV programs because they offer an exciting escape from the beige, boring reality we’ve created.

“Surrogacy” is the socially acceptable venting of certain energies in a world that has disallowed their fuller release.

The need to feel strong

In his book, Into the Wild, the author Jon Krakauer wrote, “[H]ow important it is in life not necessarily to be strong, but to feel strong, to measure yourself at least once, [and] to find yourself at least once in the most ancient of human conditions.” His idea echoes a central tenet of Nietzsche’s philosophy: All living things have a “will to power.” We all, in our deepest souls, want simply to be powerful. Humans want to get their way, but only after a challenge. We need to test ourselves and come out on top.

There is some evidence to support Krakauer’s words. People who mentally challenge themselves are less likely to be depressed and anxious. Meanwhile, the “effort paradox” states that while we tend to choose the lazier and easier option, we almost always enjoy the more demanding effort. Mountaineers relish the climb because the struggle makes the destination more rewarding than catching a helicopter ride to the top. Money earned feels more valuable than money gifted.

Interestingly, we not only value the product of effort (such as the flat-pack furniture we assemble ourselves) but also the effort itself. The mountaineer Kelly Cordes refers to this as “Type II” fun — something that “is miserable while it’s happening, but fun in retrospect.” A great many things might not be fun in the moment because they involve challenges and overcoming. Yet, we look back on such moments fondly entirely because of that effort.

So, we each have a need to test ourselves. There is pleasure in effort beyond the obvious joys of winning. There is also a more indistinct, indefinable pleasure in the act of struggle itself. It’s a fact we would do well to remember the next time we’re presented with an easier or a harder option. Yes, it might seem like a lot of effort, but for much of the time, that effort will make you deeply contented. In these surrogate activities of taking on the world, we might just feel a little more human.