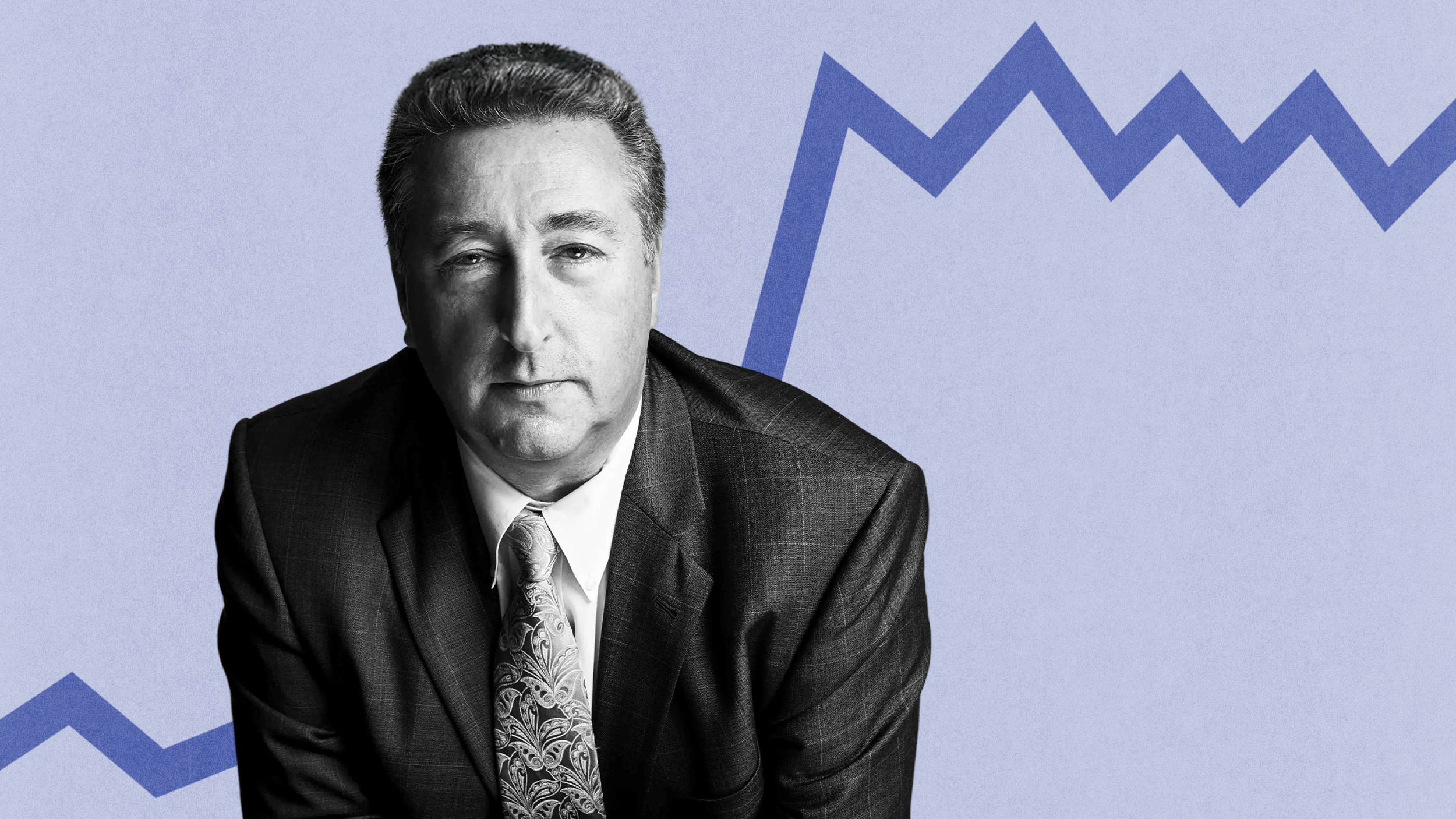

IRC chief George Rupp explains strategies for bringing refugees home.

Question: What kind of refugee crisis has the war created in Iraq?

George Rupp: We have a lot of strategies and their different from Iraq and Afghanistan, maybe I should… I’ll talk about Iraq first and then Afghanistan. In the case of Iraq, we had been working very hard with displaced people inside Iraq and also with refugees, Iraqi refugees in Syria and Jordan. And those people have all been uprooted from their homes, just to quantify it, there are 2 million uprooted people inside Iraq and another close to 2 million in Syria and Jordan and then smaller numbers in other surrounding countries. Those people… we’ve gone it and talked with them, interviewed them, there’s no question the ones outside of Iraq do not feel it is safe to return. Once it’s safe for them to return that will be the best outcome and we can hope that that happens soon. But right now, the few that have gone back to check the situation out, discovered that their homes are now occupied by others, they could not return to their home base, they would have to go to other communities that were… religious and ethnics ties were closer and as a result, they see no prospect at the moment for going back. The same goes for those uprooted within Iraq, there has been a movement of people from relatively heterogeneous places to more homogenous places and there’s not likelihood that that’s going to change and that means that people have lost their homes are not really in position to get them back. So the crisis in Iraq as far as refugees and internally displaced people are concerned still have a long way to go before its resolution. We have advocated that in a larger number of Iraqis, especially those who have worked with the US government in Iraq need fast tracks for resettlement in the United States and that’s slowly is beginning to happen. There’s only been… as I say, out of the roughly 4 million Iraqis who have been uprooted from their homes, very… a very small fraction of initially a thousand or 1,500 family went up to 10,000. Now, it’s up to 15,000 a year but the total Iraqi population, that’s being resettled in the US is miniscule compared to the overall need and that will continue to be the case even if we aggressively increase the number of Iraqis admitted, there’s no way that any significant fraction of the 4 million uprooted people will be resettled in the United States. We should do more there but that’s not going to solve the problem, we also have to provide support to Syria and Jordan, not we, the United States, the international community as a whole… because it… they have assumed an enormous burden of taking care of the Iraqis who have landed in their… on their backyard and Syria, in particular, have been extremely generous to Iraqis. They’ve allowed them to go to their schools, they’ve made housing available but this is a relatively poor country and needs to have more international assistance and has received so far until it’s safe for the Iraqi refugees to return home which will be the best outcome for everybody when that happens but it hasn’t happened yet.

Question: And in Afghanistan?

George Rupp: Afghanistan, the International Rescue Committee has been involved with Afghan refugees since the 1980s, since the Soviet invasion. We’ve worked with Afghan refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan and other parts of Pakistan on the border with Afghanistan. We’ve conducted health clinics and school programs there that really have made it possible for these Afghan refugees to develop the capacities that will allow them to return home and a great many of them have returned home. At the height, there were as many as 7 or 8 million refugees, mostly in Pakistan and Iran and all but a million and a half… at the most, 2 million have now returned back to Afghanistan. We’ve also been involved in the Afghan side of the border since 1988, so for 20 years and there we’ve worked with Afghans as they return to help them get back to their feet so they can take care of themselves and it’s been exhilarating to watch that process. I… when I go to Afghanistan, it just… it really gives me great pleasure to visit, for examples, nurseries, where we gave the saplings that first were planted 20 years ago and now they’re growing, the poplars that become the ceiling beams in their mud brick homes, we have… the teachers… the girls whom we have educated in schools in Peshawar have now returned and we’ve managed to get the credential they received in… as refugees recognized by the Afghan Ministry of Education so they are able to teach within Afghan schools. In fact, the curriculum we developed in Peshawar is now the accepted for the Dari-speaking curriculum in Afghanistan. So we feel as we’ve really had… our long-term engagement with Afghans has been very important for helping them get back on their feet.

Question: What has been one of IRC’s most successful efforts?

George Rupp: It’s called The National Solidarity Program and we have… we were centered to its development in a number of ways. The man who was the minister of rural development at the time that this program was implemented, now, 7 or 8 years ago, is a man named Hanif Atmar, who had been the head of our program… the IRC’s program in Afghanistan before he joined the government of Hamid Karzai as a minister of rural development and he knew that we had a program, really the prototype of what is called The National Solidarity Program, we’d have it Rwanda. And so he had a team of Rwandans come and work with Afghans in designing this program and here’s the way it works. We establish local village councils at the village level. We’re now involved in over a thousand villages in Afghanistan and those village councils decide what their highest priority is for development. Usually it’s a water system or a school or a bridge that connects 2 villages or otherwise in the rainy season, aren’t able to be connected with each other. But the village council itself makes the decision and then the money comes… it’s originally World Bank funding but it comes through the ministry of rural development to that local village. And it’s just tremendously exciting to see the projects that these villages identified and the ownership that they feel because they not only identified, they often contribute labor, the maximum grant that they could get from the World Bank funding is $60,000 and many of these are really quite ambitious projects but they contribute labor and local materials and are extremely pleased and proud of what they’ve created when they’re done. We are now in over a thousand villages, our staff in this program is a 100% Afghan, it originally has a smaller cadre of international staff but we have trained and brought along Afghans who are now the leaders. When I go and visit and see some of these programs, I go with our Afghan staff and witness their pride in these programs and the way there are respected and esteemed by the local villagers. And our staff is drawn from a variety of different backgrounds, many of whom were in different factions of the Mujahadin who fought the Soviets and decided, “Well, it’s now time to build rather than continue fighting.” So there are people who really have a stake in the future of Afghanistan and can make a big difference in the long term resistance of… and especially rural Afghanistan to the Taliban. Now, my hope is that the new designs that the Obama administration is developing will reinforce that kind of decentralized effort that builds capacity at a local level as the counterpart to having an Afghan government that is [in gobbled] were never given the history of Afghanistan, control all of Afghanistan. It’s really crucial that there also be a presence that is positive and connected to the central government but has a good deal of autonomy and The National Solidarity Program is really the model for that.