The implications of locating the famous “Higgs particle.”

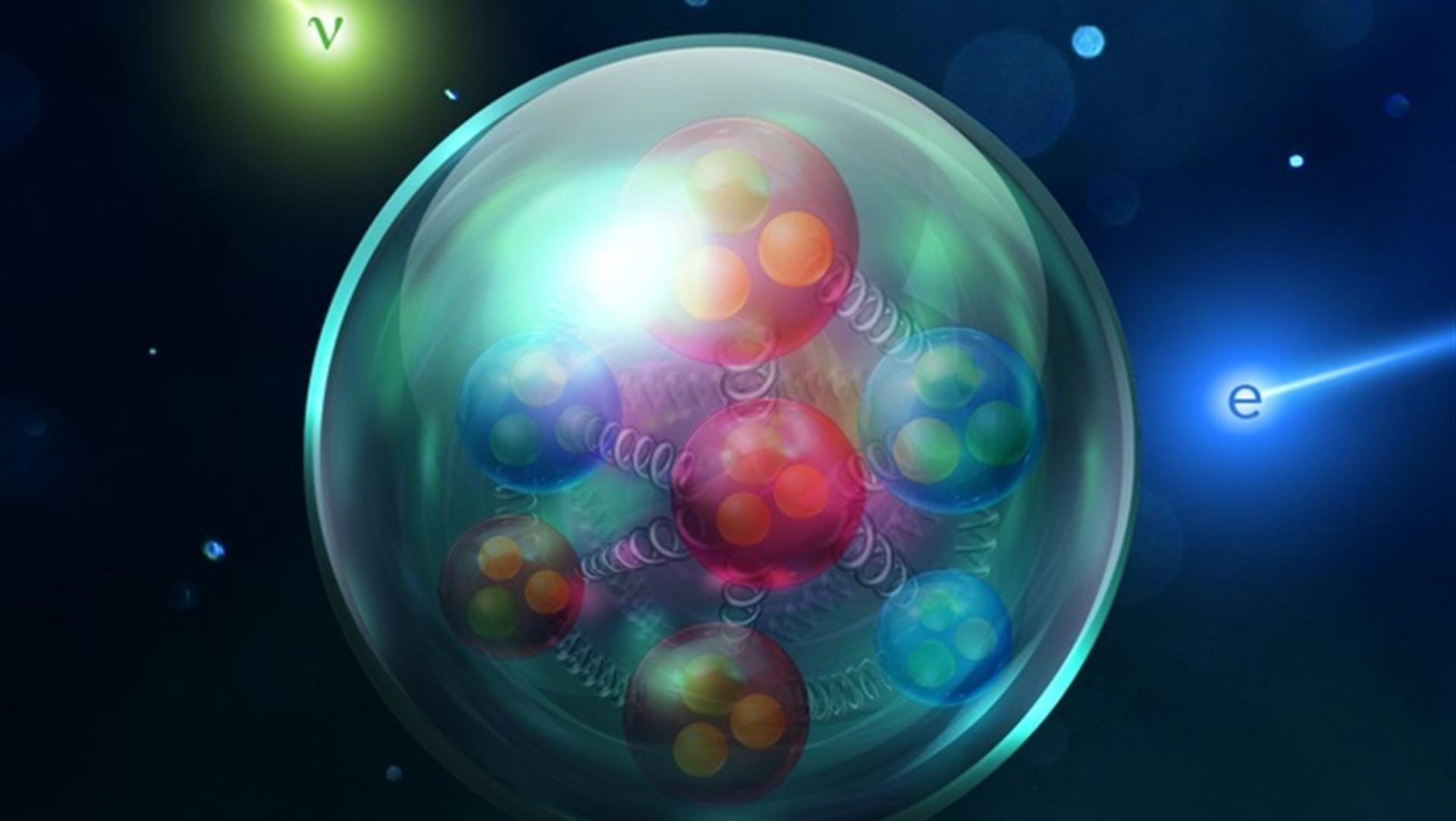

Yeah, the LHC, which stands for the Large Hadron Collider- it’s a, you know, particle accelerator. It’s gonna collide hadrons, which is- so, for example, a proton is an example of a hadron- it’s a particle that’s made up of quarks, which is thought to be the fundamental constituence of matter. And what it’s gonna- actually, it’s gonna be asking some very important questions. First of all, it’s going to be able to take matter to its fullest extreme. Okay? It’s the Extreme Sports of matter. It’s going to take matter to energy scales that will basically simulate moments right after the Big Bang, right? So, it’s gonna be able to recreate, in a sense, the

physics that we, you know, naturally don’t have access to. And in doing so, we’ll be able to see things we’ve never seen before. Now, you know, a theoretical physicist- we’re very inventive, you know, we come up with like, you know, good theories and one of the big theories that we have- we have some called the standard model- which is this model that really explains all of physics, going down to, you know, fifteen decimal points, right? After zero- centimeters, okay? Length scale- all the way up to our distance scale, all of the biochemistry- not to, you know- it’s really brought on to the same type of physics. This standard model is a theory that unifies the forces, except gravity, to explain all this physics. And it’s worked so far pretty well. And there’s one interesting thing about the standard model that is an input, a theoretical input, that we have yet to test, which goes back to the question about E=mc2. That “m” which stands for the mass- the way that enters in- it actually directly enters into the standard model, but the way “m” enters in is through a particle called a Higgs particle, named after physicist- Scottish physicist- his name is Peter Higgs, and this Higgs particle is a thing that- one of the things we are looking for at the LHC.

Question: What happens if we find the Higgs particle?

Stephon Alexander: Well, that would be- some people would say- you know, the standard model predicts- needs this Higgs particle- we have yet to find it. The LHC will be trying to find this Higgs particle. Now, if it finds the Higgs particle, then some people will say the game is over because, you know, we have this completion of the standard model. You know, this was the one Holy Grail that we’re looking for.

By the way, the Higgs particle is a very important theoretical ingredient, because it explains- it’s a particle that is a carrier of mass, okay? So it endows mass with everything else. Without the Higgs particle to interact with, everything, all the substance that we’re made up of, for example, would have no mass. It would travel at the speed of light. It wouldn’t have the mass to slow it down. The Higgs is like the glue that slows everything else down. Okay? And the problem is that the standard model does a great job and it has its Higgs particle there that predicts, but there’s this weird thing that we call fine tuning, which is you have to imagine the Higgs has a dial in it that the more, you know, you turn the dial up, this Higgs particle gets heavier or lighter. All right? Also, quantum mechanics influences this dial- it can make the dial go this way or that way, all right? Sometimes, we don’t have control over that dial. And the question is, why is the Higgs, the dial in this that dials the master to Higgs, tuned to be exactly what is necessary for us to have our mass? So that’s called a fine-tuning problem. So even if we find this Higgs, we would still have to explain that. And it appears that we are right now in a theoretical conundrum in physics right now, which is we don’t really have a good grips on this fine-tuning. And there are no good answers to that separate issue. So, now bringing that back to if we find the Higgs, that means we’ll have to deal with this fine-tuning problem, which pretty much everyone wants to avoid. Okay? But, at the same time, the basic structure of the standard model will be over with, and there’ll be no more games, no more theoretical, you know, building to do for half of the standard model. If we don’t find the Higgs, then that’s good for me because that means we have work to do, and it means that the standard model was- a big part of it was just wrong. And, also for me, it means that the way we think about mass, when it comes to particle physics, needs to be- we need completely new ideas, and that the Higgs idea, this Higgs particle, was just the wrong way- if we don’t find it.

Question: Who will conduct these experiments?

Stephon Alexander: Oh, you know, it’s a worldwide collaboration that involves thousands and thousands of people all around the world, in Geneva, Switzerland- so it’s a- a lot of people are involved in this experiment.

Question: Will the LHC be dangerous?

Stephon Alexander: Well, the energy scales are, you know- we’re talking about, you know, on the order of a thousand giga-electron-volts- remember, about ten electron volts is what it takes, you know- if you liberate an electron, right? From an atom- from hydrogen- all right- so, now, a giga-electron-volt, right? Is on the order of a billion electron volts- so we’re talking about a thousand billion electron volts. That’s the energy that we will be taking matter to, so we’re gonna access this amount of matter- I mean, the amount of energy. And we have to be able to contain that amount of energy, ‘cause it influences magnetic fields, all sorts of things, right? Your Con-Ed bill would be really, really high if you were trying to, you know, use that amount of energy. So, some theorists have tried to say, well, we can create black holes, for example, because the energy scales you can actually, you know, when you find <unintelligible>, for example, you can create- if you give me enough energy, I can convert that from empty space into matter. Or matter can annihilate into energy, so some people think, well, therefore, I should be able to create quantum black holes- I can create black holes in this lab. And then, of course, you can then argue, well, if I create a black hole right here on earth, won’t I suck everything into the black hole? Right? So, and then if you go and ask a theorist, is that gonna be catastrophic? I mean, I don’t know, I can’t predict that. So, that’s kinda where things go, but there’s a near to zero percent chance that anything bad would happen. But, on the flip side, we’ve never actually seen or experienced nature at that energy scale, so we just don’t know what’ll happen.