“The Little Book of Aliens” begins

- Never before has there been so much interest in the question of whether there is life on other worlds, and never before have we gotten so close to getting answers.

- The question, “Are we alone?” has been asked for 2,000 years, but scientific inquiry on the matter started in the 1950s. For the first time, we are now ready to collect real data.

- There is so much to take in for anyone developing an interest in the topic. So, it is time for me to write a book.

Everybody loves aliens. Everybody is talking about aliens. From exoplanets and the James Webb Space Telescope, to endless discussions about Unidentified Flying Objects and Unidentified Aerial Phenomena, aliens are in the news all the time.

It seems clear we are living in a very particular moment when it comes to understanding the possibilities of life in the Cosmos. Never before has there been so much interest in the question of whether there is life on other worlds, and never before have we gotten so close to getting answers. So, what is a person to do who is interested in this most important question at this most crucial time?

In my case, the answer was simple: Write a book.

A question asked for 20 centuries

People have been asking, “Are we alone?” forever. You can read Aristotle and Democritus slugging it out over the issue 2,000 years ago. Over the 20 centuries to follow, the subject was never settled, and the arguments never died down.

But then in the 1950s, the first steps were taken toward making alien life a topic for scientific study. The decade started with Enrico Fermi framing his famous “paradox” over lunch at Los Alamos in 1950, wondering why aliens from more ancient parts of the Universe had not already visited us. In the middle of the decade, the Miller-Urey experiment gave us insight on how life’s basic molecules are created, mimicking a young Earth in a test tube. Finally, at the end of the decade, Frank Drake carried out the first true search for alien life, using the giant radio telescope at Green Bank, West Virginia.

Over the next 20 years, the science of searching for life in the Cosmos pushed forward. We sent probes to all the planets, and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) continued with a range of new and important ideas.

Then things went a bit dark. SETI starved for funding as a bunch of politicians used it to score points, beating on NASA for “wasting taxpayer dollars.” And after the Viking missions in the 1970s, it looked Mars was just a dead rock. Folks stopped thinking of the solar system as a place to hunt for life. It was a depressing time in the search for cosmic life — a time that luckily did not last.

The search for aliens goes mainstream

After the late 1990s, the field we now call astrobiology roared back to life. First, Mars suddenly got interesting again as a series of landers showed conclusively that the Red Planet was once blue. There had been water on Mars billions of years ago — a lot of water. Maybe Mars formed life back then, as well. Maybe life is still there. Just as important, in 1995 we discovered for the first time an exoplanet orbiting a distant sun-like star. This was the beginning of what I like to call the “exoplanet revolution,” and we now know that every star in the sky hosts a family of alien worlds. With all those alien worlds, the chance that there is alien life — and perhaps alien civilizations — got much higher.

Finally, over the last few years, UFOs and UAPs have suddenly become mainstream news. Three videos released by the U.S. Navy, along with a government report released last year, brought the subject out from the tin-hat shadows and left everyone wondering, “Should I take this seriously?”

So why is all this a problem? Simply put, it is a lot to take in.

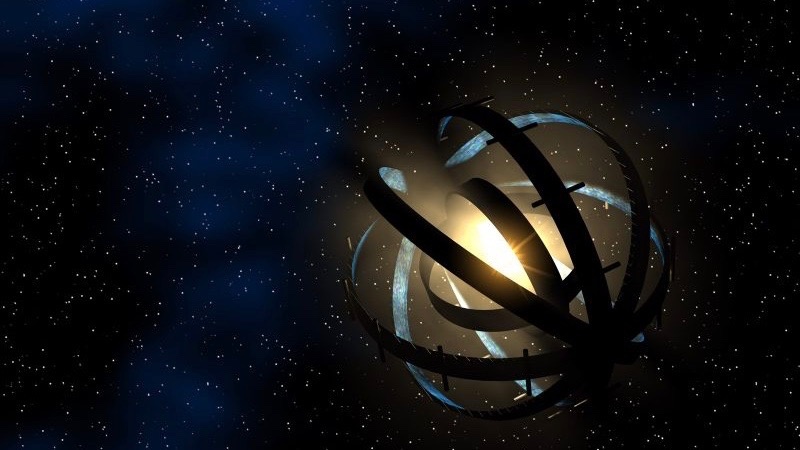

If you really want to understand what’s going on now, you also need to understand what went on then. Scientists like me studying astrobiology already know about the Drake Equation, habitable zones, and Dyson Spheres, to name a few elements of the necessary background. Such topics frame what we are doing now and what we will be discovering tomorrow. You need to know all that background to make sense of what is happening. At the same time, if you want to know what we will be discovering tomorrow, you also need to know about stuff we’re working on right now, topics with names like atmospheric characterization, biosignatures, and technosignatures.

The issue is the same with UAPs. Is it time to carry out a true scientific study of UAPs? Well, what would that look like? What issues need to be addressed? How do we think about technologies that aliens might have, if the UAPs have anything to do with aliens? (I am highly skeptical they do, but how should we apply good science to the question?)

So that is why I have begun a new book project. It is called The Little Book of Aliens, and if I am diligent, it should be out in the fall of 2023. The plan for the book is 50 short chapters or sections, each of which should be mostly self-contained. My goal is to give folks a sharp and easily accessible entry point to all the stuff they need to understand and participate. It will be a series of discussions about the most exciting and important scientific endeavor in human history.

That is not hyperbole.

We are finally in a position to start getting real data that can help us answer the question, “Are we alone?” It’s a thrilling moment to be alive, and I want everyone to be in on the ride.