Ask Ethan: Can Two Planets Share The Same Orbit?

While a “counter-Earth” may be impossible, there are three other ways it could actually work out.

“We are not like the social insects. They have only the one way of doing things and they will do it forever, coded for that way. We are coded differently, not just for binary choices, go or no-go. We can go four ways at once, depending on how the air feels: go, no-go, but also maybe, plus what the hell let’s give it a try.” –Lewis Thomas

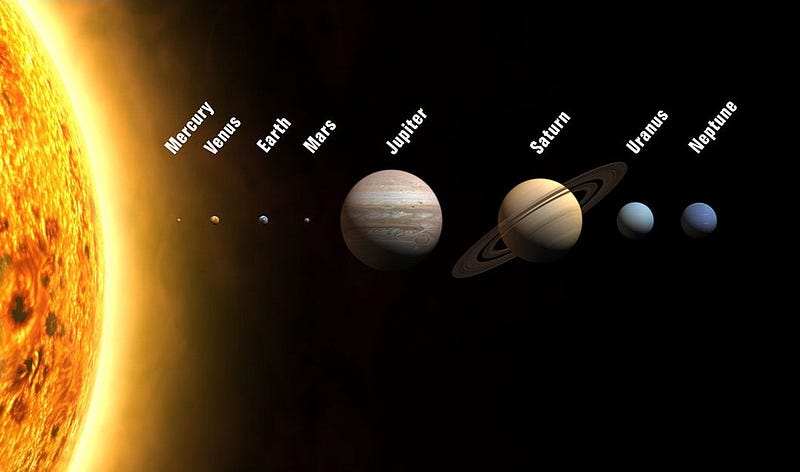

Despite the dangers an occasional comet or asteroid strike might bring, our Solar System is actually a wonderfully stable place, with all eight planets expected to remain in their orbits, stably, for as long as the Sun lives. But are all solar systems this way? After sifting through our questions and suggestions for Ask Ethan this week, I selected this outstanding question by Dee Hurley:

Is it possible to have a solar system with two planets sharing the same orbit?

It’s a really good question, and our own Solar System offers some clues to the answer.

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), there are three things an orbiting body needs to do in order to be a planet:

- It needs to be in hydrostatic equilibrium, or have enough gravity to pull it into a spherical shape. (Plus whatever rotational effects distort it.)

- It needs to orbit the Sun and not any other body (like another planet).

- And it needs to clear its orbit of any planetesimals or planetary competitors.

This last definition, strictly speaking, rules out two planets sharing the same orbit, since the orbit wouldn’t be cleared if there were two of them.

But why worry about technical definitions? Let’s worry, instead, about whether it would be possible to have two Earth-like planets that share the same orbit around their star. The big worry, of course, is gravitation, which can ruin a dual orbit in one of two ways: either a gravitational interaction can “kick” one of the planets very hard, either sending it into the sun or out of the solar system, or the mutual gravitational attraction of the two planets can cause them to merge, resulting in a spectacular collision.

This latter case is, in fact, something that happened to Earth when the Solar System was only a few tens of millions of years old! The collision resulted in the formation of our Moon, and very likely caused a major resurfacing event on our planet.

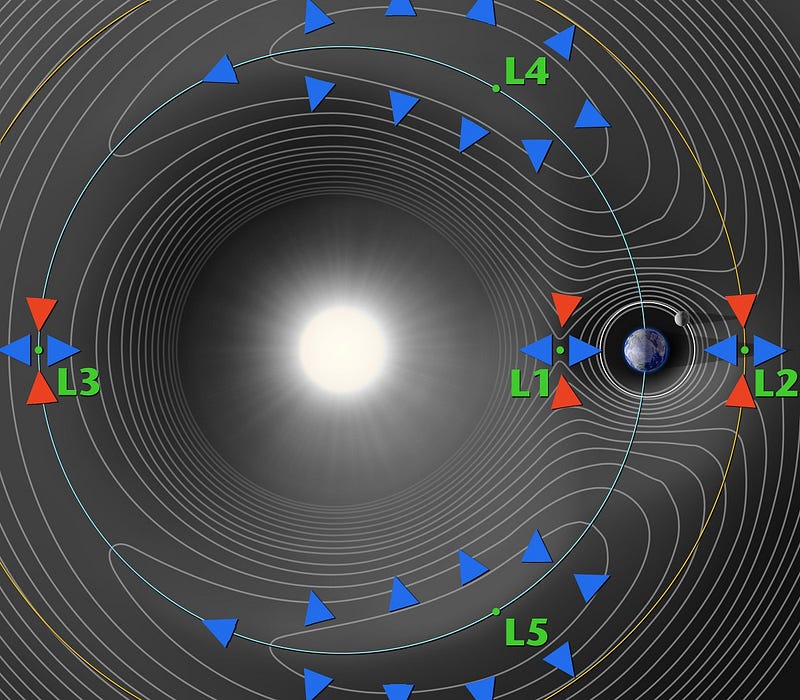

Two planets don’t do a great job of occupying the same exact orbit, because there’s no such thing as true stability in these cases. The best you can do is hope for a quasi-stable orbit, meaning that while, technically, on infinitely long timescales, everything is unstable, you can obtain configurations that last billions of years before one of these two “bad” things occurs. And for that, I want to introduce you to a concept: Lagrange points.

If you only considered two masses — the Sun and a single planet — there are five points (known as Lagrange points) around each one where the gravitational effects of the Sun and the planet cancel out, and all three bodies move in a stable orbit forever. Unfortunately, only two of these Lagrange points, L4 and L5, are stable; anything that starts out at the other three (L1, L2, or L3) will unstably move away, and wind up colliding with the planet or getting ejected.

But L4 and L5 are the points around which asteroids collect. The gas giant worlds all have thousands, but even Earth has one: the asteroid 3753 Cruithne, which is presently in a quasi-stable orbit with our world!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRaqYClJ154

Although this asteroid in particular isn’t stable on billion-year timescales, it is definitely possible for two planets to share an orbit just like this. It’s also possible to have a binary planet, which would be a lot like the Earth/Moon system (or the Pluto/Charon system), except with no clear “winner” as to who’s the planet and who’s the moon. If you had a system where two planets were comparable in mass/size, and only separated by a short distance, you could have what’s known as either a binary or double planet system. Recent studies indicate that this is, in fact, possible.

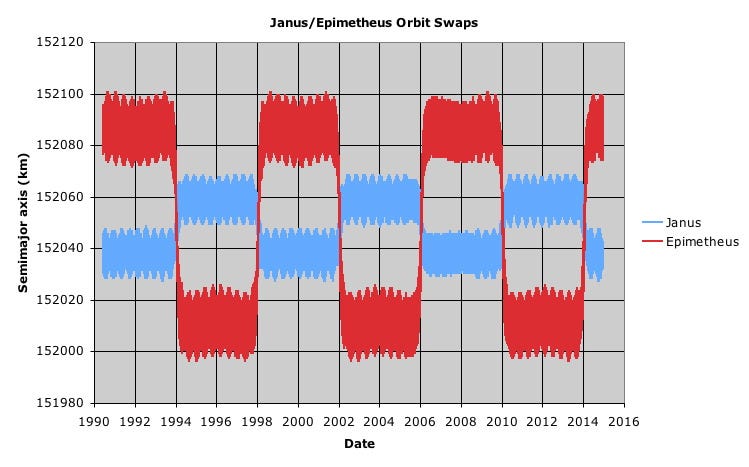

But there’s one more way to do it, and this is something you might not have thought was stable: you can have two planets in two separate orbits, one interior to the other, where the orbits swap periodically as the inner world overtakes the outer world. You might think this is crazy, but our Solar System has an example where this happens: two of Saturn’s Moons, Epimetheus and Janus

Every four years, whichever moon is interior (closer to Saturn) comes to overtake the exterior one, and their mutual gravitational pull causes the inner moon to move outward, while the outer moon moves inward, and they swap.

Over the past 25 years, we’ve observe these two moons dance quite a bit, and as far as we can tell, this configuration is stable over the lifetime of our Solar System. In other words, it’s totally conceivable that we’d have a planetary system somewhere in our galaxy with two planets (rather than moons) that do exactly this!

The unfortunate news, at least for now, is that out of the thousands of discovered planets around other stars, we don’t have any binary planet candidates yet. (You may have heard of one a few years ago, but it was retracted.) Of course, our technology hasn’t progressed to the point where we’ve discovered moons around exoplanets yet, either, and yet we fully expect them to be there.

The reality is that these orbit-sharing circumstances are expected to be rare, but not so exceedingly rare that we don’t expect to see it ever. Give us a better planet-finding telescope, a million stars and about 10 years, and I’d be willing to bet we’d find examples of all three cases of planet-sharing orbits. The laws of gravity and our simulations tell us they ought to be there. The only step left is to find them.

Submit your questions and suggestions for the next Ask Ethan here, and if you’re chosen, you’ll win a free Year In Space calendar!

Leave your comments on our forum, support Starts With A Bang here on Patreon, and pre-order our book, Beyond The Galaxy; the 1st chapter is free!