Some cancers shouldn’t be treated

- In the war on cancer, we’re detecting and aggressively treating more malignant tumors than ever before. But at the same time, we’re also over-treating more cancers then ever.

- Cancer exists on a spectrum. Some have less than a 5% chance of progressing over two decades while others have more than a 75% chance of progressing over one to two years.

- For low-risk cancers, patients and their doctors should consider “active surveillance” of their tumor rather than opting for immediate treatment in the form of surgery or chemotherapy.

The collective effort to improve the treatment of cancer is often described as a “war,” as if malignant tumors are a scourge to be ruthlessly rooted out and destroyed the second they are detected. But oncologists are now increasingly calling for a truce in the case of many cancers. The fight might have gone too far.

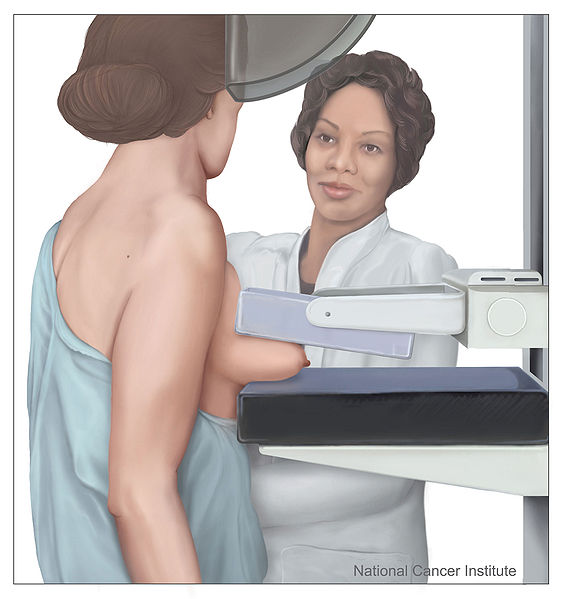

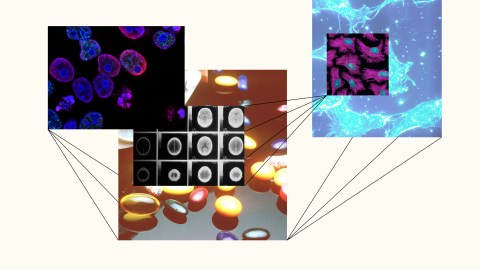

As cancer screening has grown more powerful in scope and increasingly widespread, we’re detecting more cancers than ever before, and catching them earlier. A CDC study published last year found that between 2009 and 2018, the number of people diagnosed with cancer climbed from 1,292,222 to 1,708,921. For aggressive cancers of the lung, colon, and pancreas, this advanced detection can be a lifesaver. But for low-risk cancers including, for example, prostate, urethral, thyroid, certain non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and some areas of the breast, a positive test can lead to emotional stress and unneeded, physically-taxing treatment.

Some cancers shouldn’t be treated

Cancer, what many people instinctively view as a death sentence, actually exists on a wide spectrum, ranging from ultra low risk, with less than a 5% chance of progressing over two decades, to extremely high risk, more than a 75% chance of progressing over one to two years. Since cancer treatment, including chemotherapy and surgery, can be costly and life-altering, the goal should be to wield these weapons in the cases they are called for, and keep them sheathed when they are not.

Instead, for low-risk cancers, the modus operandi should probably be what’s termed “active surveillance,” defined by the National Cancer Institute as “a treatment plan that involves closely watching a patient’s condition but not giving any treatment unless there are changes in test results that show the condition is getting worse.”

Recently, a long-term study comparing active surveillance of prostate cancer with aggressive therapies like surgery and radiotherapy found no difference in survival rates over 15 years of follow-up. A 2021 study comparing up-front surgery of melanoma and simple ultrasound monitoring also resulted in the same overall risk of death. Repeated studies of active surveillance for thyroid cancer also reported excellent outcomes for patients.

“I think the new role for the physicians is to be a coach, and to really try and help explain all this complicated data, and to help people make a choice that’s right for them,” Dr. Laura Esserman, a breast cancer surgeon and oncologist at the University of California-San Francisco, told CBS News in 2017.

Don’t call it cancer

One method doctors could take with their patients is to refrain from calling a very early, non-aggressive tumor “cancer.” A 2019 study found that volunteers presented with a hypothetical diagnosis elected surgery over surveillance far more often when a tumor was described as “cancer” versus a “nodule,” a less charged term.

Doctors could also reduce the amount of screening they do, particularly for healthy adults or older adults who likely would opt not to treat a diagnosed cancer anyway.

Unfortunately, the drive for early detection and treatment can be tough to dislodge, Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, a prominent cancer researcher, told CBS News. “Ironically, the more over-diagnosis that a screening test does, the more popular it becomes, because there’s more people who feel they are ‘survivors’ because of screening,” he said. “Although it happens to be a cancer that was never going to bother them. They’ll never know that.”