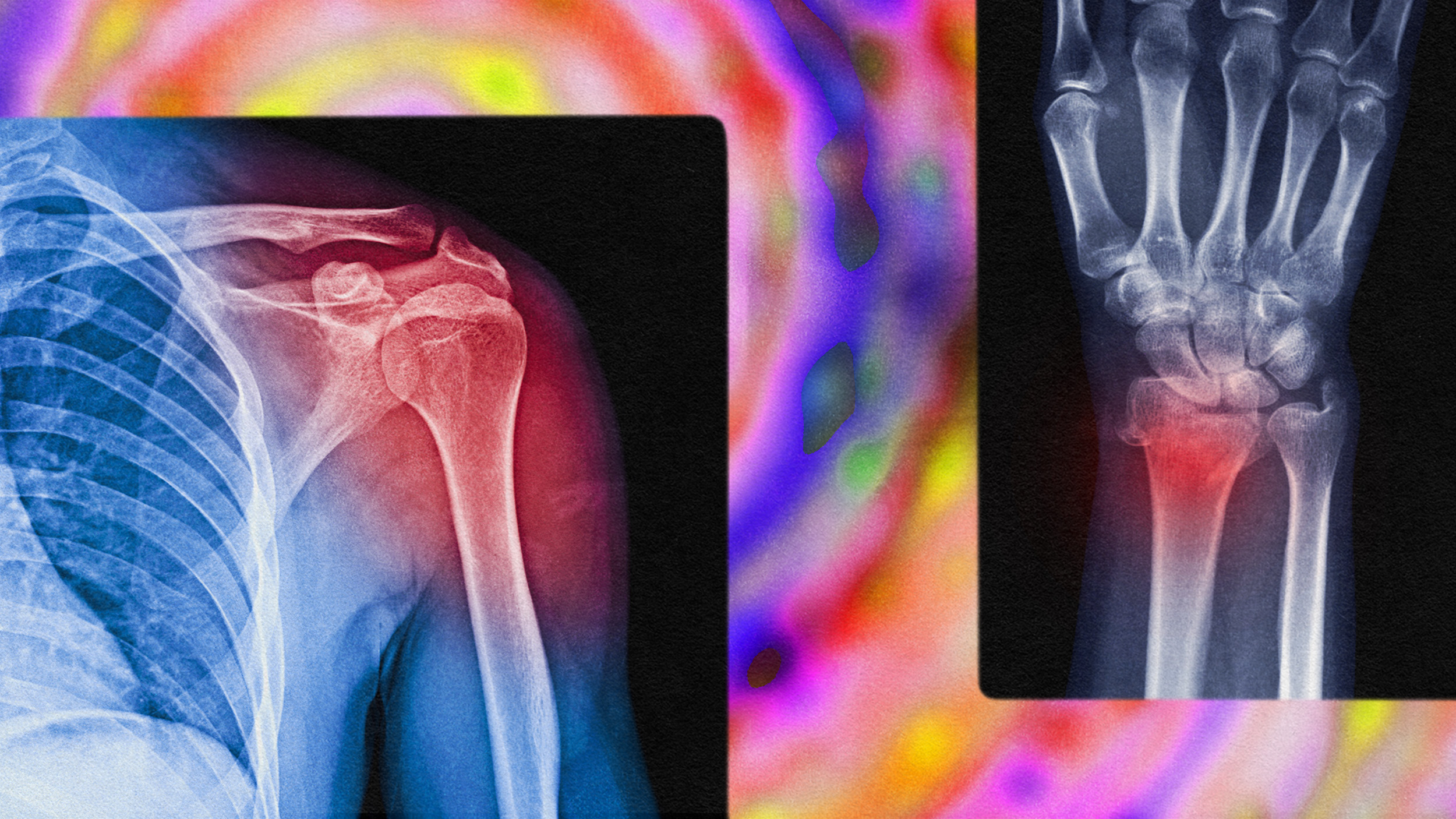

Increasing numbers of people are in pain. How do we cope?

Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

- Physical and emotional pain are not that distinct, given that both are routed through a single brain region.

- A new study at NYU shows that physical pain can lessen the effects of depression and emotional duress.

- Holistic methods for dealing with both physical and emotional pain should be considered.

Pain is one of the most confusing aspects of human physiology. From an evolutionary perspective, pain is either a signal that something is wrong (broken bone; stomachache) or a cautionary tale informing us to not repeat an activity (touching a hot stove). Pain often resolves when the noxious stimulus is removed—the form of pain related to tissue damage. Then we enter the world of emotional pain, which itself is intimately related to physical pain.

Let’s begin with the physical. You stub your toe, immediately sending a signal up your spinal cord to your frontal anterior cingular cortex (ACC), which assess the meaning of this pain. The ACC plays an important role in error detection, noting the distance between what you expected (you were walking to the bathroom) and what occurred (your foot caught the edge of your bed frame because you were staring at your phone). Tissue damage has indeed occurred. It hurts.

An interesting study placed subjects in a brain scanner tossing a ball with two other (virtual) people. After a while, those players decide to stop throwing to you. You’ve been outcast and the rejection stings. Your ACC activates. As Robert Sapolsky writes, “as far those neurons in the ACC are concerned, social and literal pain are the same.”

The ACC activates when you get an electric shock. Incredibly, if you watch a friend get shocked, the same region fires. We call this empathy, the ability to perceive what another is feeling, yet this goes a step further: you actually feel their pain. Sapolsky notes that both dread and depression can be physically felt. Research has shown that ibuprofen alleviates emotional pain as well (in women, at least).

Pain management is one of the hardest aspects of medicine. Diagnosing disease from the perspective of pain alone is challenging. When I broke my femur the emergency room doctor knew exactly what had happened. Yet how many different ailments begin with a stomachache or a headache?

Then there’s our relationship to pain. We live in the most comfortable age in the history of our species. We’re also under the illusion that a pill can dissolve pain, be it physical or emotional, by blocking neurotransmission of specific chemicals. Pain alleviation is a great feature of modern medicine, yet when you create a society expectant of constant relief you cheat its citizens from important lessons about the nature of physiology. Many of our pain relief efforts, from antidepressants to aspirin, are driven by profit maximization, not compassion.

While a number of techniques for alleviating pain exist, without an honest and open discussion about the nature of pain people find their own methods. A new study published in the journal Emotion has found that the intentional onset of physical pain (cutting, for example) helps people deal with emotional distress. It also clues us in to the conceptual world of pain.

Ashley Doukas at NYU Langone Health conducted this research after she studied body-based coping mechanisms such as deep breathing and smiling. The clinical instructor says,

“I became interested in the topic of pain because a great deal of the literature on non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) indicates that one reason people engage in self-injurious behavior is to regulate extreme emotional states.”

Doukas noticed that even healthy controls felt better emotionally after experiencing physical pain. It’s hard for your brain to focus on two forms of pain simultaneously. On top of this is hormesis, an internal form of vaccination: a little bit of a toxin makes you stronger. In exercise studies, this is similar to purposefully tearing your muscles after lifting weights, a process that ultimately makes them stronger. The neurological reaction runs parallel: while you struggle with increasing loads during workouts, you feel better for hours after (if not a bit sore).

Nick Kyrgios of Australia feels the pain during his fourth round match against Rafael Nadal of Spain on day eight of the 2020 Australian Open at Melbourne Park on January 27, 2020 in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo by James D. Morgan/Getty Images

For the study, Doukas and team recruited 60 test subjects to look at upsetting images. They were then provided with four methods of coping, two cognitive and two physical. The cognitive methods were distracting yourself with another thought or mentally changing the meaning of the image. As for physical means, subjects could self-administer an electric shock, either painful or painless.

Over the course of 16 trials, two-thirds (67.5 percent) of volunteers self-administered at least one painful electric shock. The average was two per person, with 13 being at the high end. Doukas hopes that this information helps to de-stigmatize those who purposefully engage in painful behavior to deal with emotional duress.

“While of course we do not want people to put themselves at risk for infection or accidental death, the fact is that human beings use pain to manage their emotions all the time — think of an intense massage to relax, and putting extra hot sauce on tacos to make them more intense and enjoyable. While the injurious aspect of NSSI can be alarming to many, the infliction of pain on oneself may not be inherently pathological, and may actually be making good use of some basic biological responses to pain, such as endorphins.”

We often discuss the brain-body connection as if they’re separate domains. We can actually witness the workings of that connection in the form of our nervous system. Everyone recognizes that injury can lead to depression while heartache can result in the manifestation of physical disease. If cutting seems a strange choice for dealing with stress or anxiety, remember that for roughly 2,000 years bloodletting was the go-to by doctors for a variety of ailments.

This is not a call for sanctioned cutting. We know that in most cases draining blood from your body is the opposite of healing. Yet we’re also aware that the distance between physical and emotional pain is not far. Creating a holistic pain management paradigm moving forward would be in our best interests. While some region-specific remedies are important, epidemics such as with opioids, depression, and obesity show that we are not managing pain well.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His next book is Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.